By Matt Dhillon

In the staggering summer heat, Kendall King digs her fingers into the dark topsoil of a new garden bed. She’s kneeling on the back lawn of Visible Records, a gallery and studio space in Charlottesville’s Belmont neighborhood. In the garden, three tall tomato plants climb out of their cages between shoots of okra and some basil. King has been looking for space to plant peppers, too, but she isn’t sure there’s enough room.

A thousand miles away, in Boley, Oklahoma, Darrell Morris sits in the John Lilley Correctional Center, picturing the same garden—his garden.

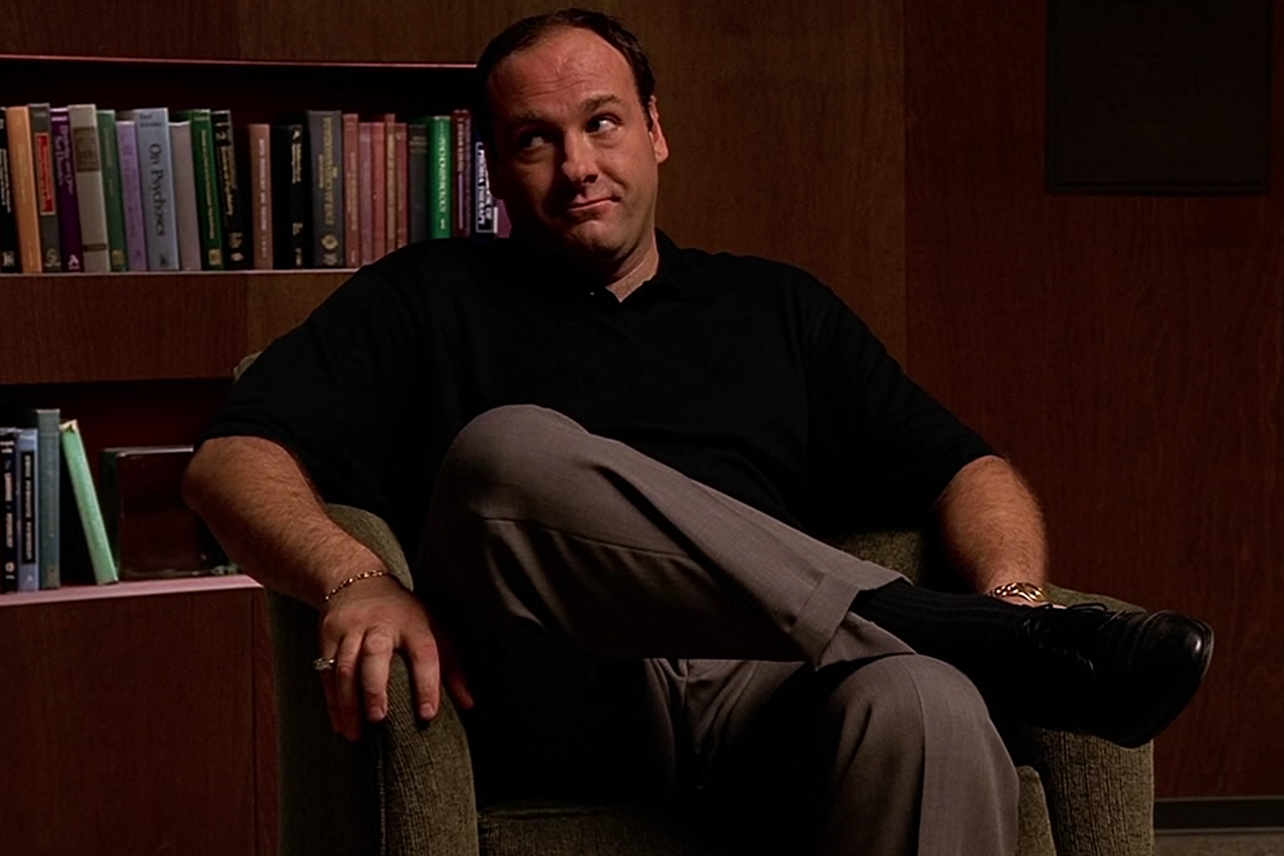

The plot in Belmont is made to match the solitary confinement cell where Morris has spent portions of the last 14 years. A low concrete wall surrounds the garden—a cramped nine-feet by six—and four concrete slabs fill some of the space within. One slab represents the outline of Morris’ bed, one represents the combined toilet and sink, and two more show where a chair and desk might sit.

The steel bars of a jail cell on one side of the garden stand at one end in contrast to the plants within, giving the structure a tension between feelings of constriction and growth.

That contrast is intentional to this interactive, living sculpture. This is a solitary garden, one of four newly installed at Visible Records. The concrete and bars are made to replicate the cell of an inmate locked in solitary confinement, the tiny perimeter that is their world for at least 23 hours a day.

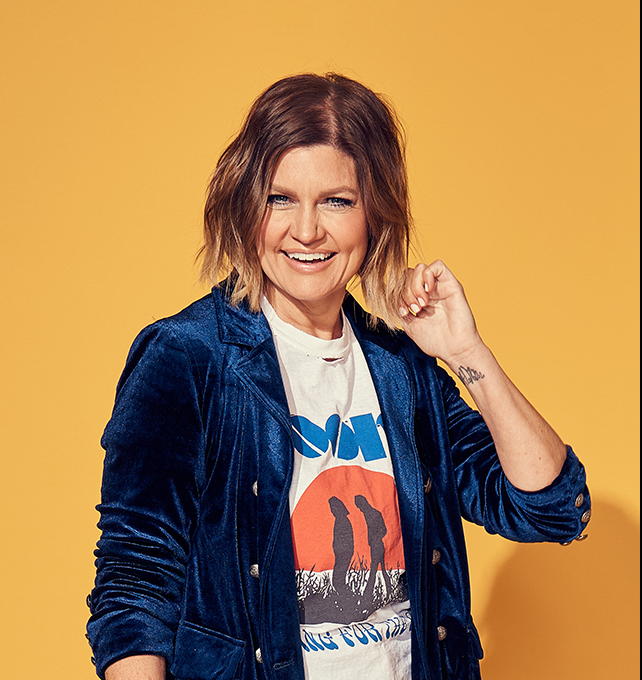

Each solitary garden is planted under the direction of an incarcerated individual, the solitary gardener, who has spent time in solitary confinement. The small plot inside the concrete serves as a kind of link to that person, mirroring his cell. Visitors to the garden can, in that small way, share space with a person who is kept in extreme isolation. King, the studio manager at Visible Records, and Morgan Ashcom, co-founder and director, were inspired to bring the project to Charlottesville by the original designs of New Orleans-based artist jackie sumell (who does not capitalize her name).

Solitary confinement is known to exacerbate mental and physical illness for those incarcerated. A recent study from researchers at the University of North Carolina found that, compared to general population prisoners, people who had spent any time in solitary confinement were 24 percent more likely to die in the first year after release, and 78 percent more likely to commit suicide in the first year. The United Nations considers 15 consecutive days of solitary confinement to be torture.

Morris was incarcerated in 2007 following an altercation with police in his home. Some who knew him before his arrest say he was a helpful member of his community, and that continuing his imprisonment benefits no one. “What is the purpose of punishing Darrell anymore?” says King’s mother, an old friend of Morris. “There is no purpose.”

King herself had never connected with Morris personally until she offered to collaborate with him on a solitary garden. In his letters to King, Morris writes about his history of raising a garden: “I love to grow my own food and have always had a garden when possible.”

“He’s telling me about things he likes and wants, like okra, and tomatoes, and things he grew himself when he wasn’t confined,” she says. “And the opportunity to know that you are manifesting that somewhere else, outside of this confined space, I think is really powerful.”

Because the prison’s mail system is slow and often unreliable, King gets most of her updates through her family, who check in on Morris when they can by phone. “I think when you’re isolated in prison, any connection to anything is amazing because you don’t have any connection to anybody,” King says.

And while the garden is a small link to the outside world for Morris, it’s also a way for the outside world to look into his cell. One of the most common reactions to a solitary garden is shock at the cell’s structure. “Our society does a very good job of invisibilizing prisons and the people who are in them, and just getting it out of our faces as much as possible,” King says. “And I think that the physical object of [the solitary garden] does the opposite of that.”

Each garden is a portrait of an incarcerated individual, says sumell. There are currently 19 different garden installations, based on sumell’s original concept, around the country, including the four now growing in Charlottesville. She started the project in New Orleans in 2013, following 12 years of collaborations with prisoners in the Louisiana State Penitentiary, a massive facility known as Angola, named after the plantation that once occupied the land.

A professed prison abolitionist, sumell hopes the project will call attention to what she calls a failed system of mass incarceration.

The United States incarcerates its citizens at the highest rate of any country in the world, with seven out of every 1,000 people—2.3 million in total—currently incarcerated. Twenty percent of those incarcerated are serving time for drug-related offenses, reports the Prison Policy Initiative. Black people are incarcerated at disproportionate rates: they make up 12 percent of the nation’s population and 33 percent of the prison population, according to the Pew Research Center.

In sumell’s view, one of the foundational problems of this system is that it prioritizes punishment instead of healing. She describes the justice system more as a tool of coercion than of actual justice.

“Abolition does not mean that you don’t respond to harm, it just means you don’t respond to harm with punishment,” she says. “But that is moving through processes of accountability that are much slower than the immediate, knee-jerk response of punishment.”

The green growth inside the solitary gardens seems almost rebellious inside the strict cell. Here, participants are choosing to grow instead of destroy and choosing to heal instead of harm. The next evolution of solitary gardens will be even more explicitly connected to healing. In the Prisoner’s Apothecary project, solitary gardeners will learn about the medicinal properties of plants, and volunteers will use those plants to build an apothecary and offer the medicine to people directly impacted by mass incarceration.

sumell hopes Solitary Gardens will encourage viewers to envision a world without prisons. “That is just the job of an evolving society,” she says. “To dream together.”