Living here, in the shadow of Monticello, you’ve likely heard of Shadwell, the birthplace of Thomas Jefferson. There’s even an historic marker for it, along 250 East, south of Pantops. But next to the marker, all there is to see is rolling pasture and a herd of not-very-historic-looking Black Angus cattle.

Two hundred and sixty years ago, that pasture was part of the Shadwell plantation owned by Peter Jefferson (and subsequently by his son Thomas). The property also included a riverside commercial and industrial center that was active until the mid-19th century, when the area reverted back to farmland. In the last few months, though, Shadwell has been a busy place again: A small crew of dedicated stonemasons have been at work, securing a little piece of the area’s past.

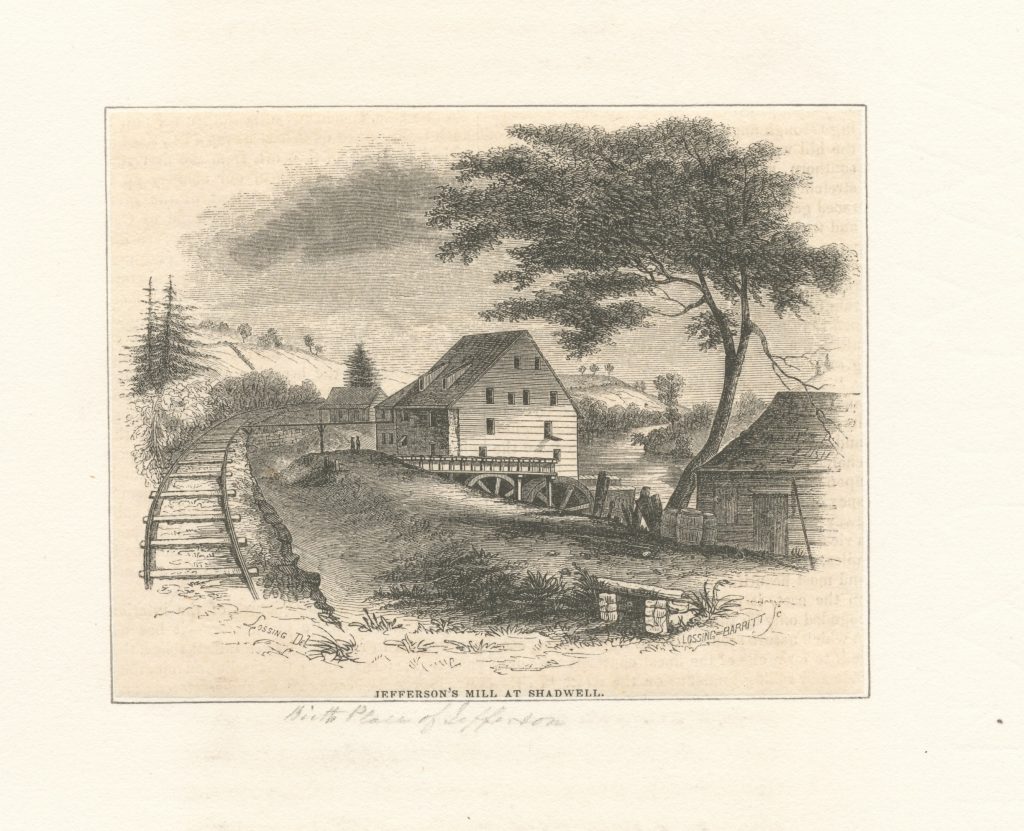

These masons are working on the only visible remnants of Jefferson’s ownership of Shadwell: the large grist mill constructed there in 1807, used to grind wheat grown on the area’s plantations so that the grain could be sold. Nothing survives of the building where Jefferson was born in 1743, though in 1991, archaeologists uncovered a cellar foundation that they believe shows the outline of the house. For the most part, the woods have reclaimed the site along the Rivanna’s banks, but the mill’s footprint—about the size of half a basketball court—is still clearly visible, along with parts of the foundation and one corner of the building that’s almost two stories high.

Right now, that corner is protected by scaffolding draped with plastic sheeting and surrounded with wheelbarrows and buckets for building supplies. A crew of four is carefully using custom-made mortar based on formulas used in the 19th century to secure the walls and repoint the stone layers that are still standing.

Their firm, Dominion Traditional Building Group, specializes in masonry reconstruction of historic buildings using historical methods. The company has worked on the Monticello Mountaintop Project, James Madison’s Montpelier, St. Andrew’s Catholic Church in Roanoke, and other historic sites around the Mid-Atlantic. Mike Ondrick, one of the company’s founders (and head of the Shadwell crew), has worked on more than 1,800 structures in his 30-plus years as a master stonemason. But on this project, the charge is not reconstruction—just stabilizing the structure to prevent further collapse.

Over the years, interpretive work at Shadwell has revealed important details about life in 18th and 19th century Albemarle. Archaeologists have uncovered Native American artifacts on the site, too. “When Peter Jefferson moved here, this was still the frontier, with Native American groups traveling between their homeland, and Williamsburg, the capital of Virginia,” says Monticello research archaeologist Derek Wheeler in a Monticello-produced video about the site.

What’s brought activity back to Shadwell is plans to extend the Old Mills Trail, which runs along the Rivanna from Darden Towe Park past Woolen Mills, southward to connect with the proposed network of trails running from the Chesapeake to the Shenandoah Valley. The route being discussed would use the railroad right-of-way going right past the mill site—which presents both opportunities and challenges.

“We are working with Albemarle County on easements [for the proposed trail],” says Gardiner Hallock, vice president for architecture, collections, and facilities for the Thomas Jefferson Foundation, owner of about half of the original Shadwell property. With increased public traffic, Hallock says there are plans to install interpretive signs explaining the mill’s history and its function in the economy of Jefferson’s time.

But more people walking by the site also means “we had to stabilize it now, before any more is lost—and keep it safe,” Hallock explains. Along with signage, there will be fencing to keep wanderers out of the ruins. On the current worksite, a large sign warns random hikers who might feel like climbing the 200-year-old walls: “STOP. THINK. Have you been trained on scaffolding usage?”

Pre-pandemic, Monticello offered tours of the Shadwell property, led by Wheeler, about once a year. Whether those tours will resume is uncertain. But Hallock is excited about using the mill to help show another side of life in central Virginia during the Jefferson era.

“This site is the last part that’s above ground of the extensive operations [at Shadwell]—two mills, a miller’s house,” he notes. “The local economy processed its grain there. In the 1830s, there was a cotton mill with about 100 employees a little upriver.” Over time, the complex also included a barrel-making shop operated by Jefferson’s enslaved coopers, a sawmill, several stores, and houses.

Then, as always, things changed. In the late 1700s, farmers had shifted from tobacco to wheat (thus the need for mills), but, within a few decades, wheat gave way to apples as the area’s major crop. The railroads made the waterways less important to commerce; the cotton factory burned down in 1851; and gradually the Shadwell “town center” disappeared, leaving only a haphazard stack of stones behind.