New Hill Development Corporation got its start from a series of conversations about the history and future of Black wealth in Charlottesville. In early 2017, Wes Bellamy and Kathy Galvin, then City Council members, gathered a group of Black entrepreneurs and community leaders to talk about Black representation in city development. But the scope of the discussion quickly grew.

They wanted to develop sustainable economic power for Black communities, so they set out to understand the history of that power.

They uncovered a story that is only now becoming more widely known, a story about a Charlottesville that was majority-Black after the Civil War, about a Charlottesville whose largest landowners were Black, and about a Charlottesville with a flourishing Black entrepreneurial class, concentrated especially in Vinegar Hill. They also uncovered a story about white legislators who passed laws meant to keep Black people from acquiring new land, about white city officials who neglected the infrastructure in Black neighborhoods, and about white city planners who decided to raze Black property, using the infrastructure they had neglected as justification, in order to make space for new development. In short, they found a story of the suppression and destruction of Black wealth.

“Just as there was intention around destroying something, there has to be intention around building something back,” says Yolunda Harrell, one of New Hill Development’s founders and now its CEO.

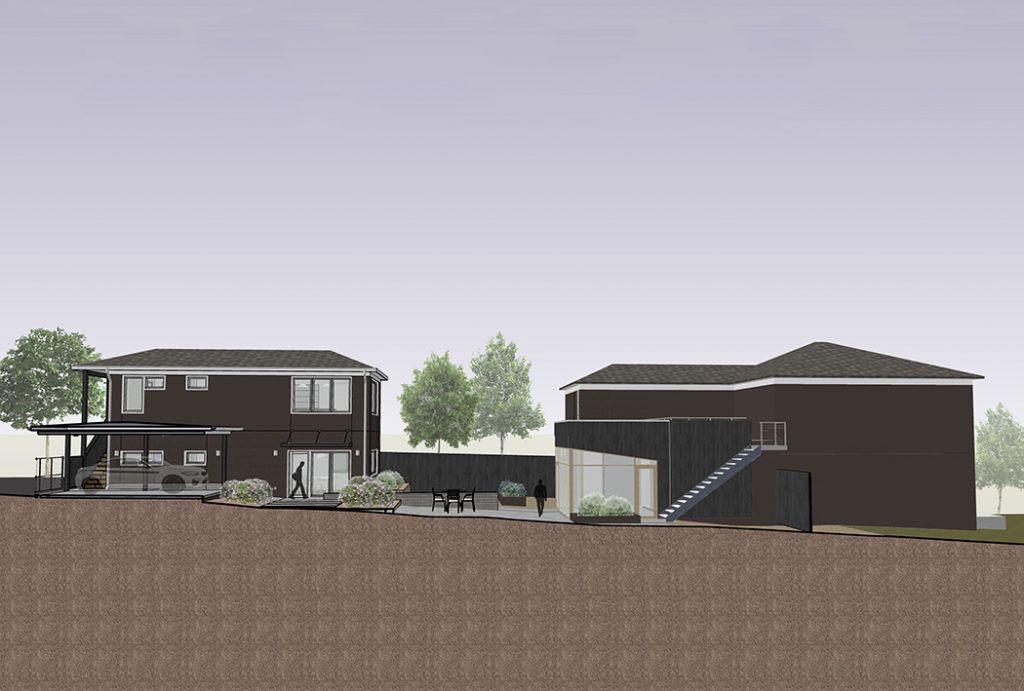

Over the last five years, New Hill has been building. Its first major initiative, the initiative that gave it its name, was a small area development plan that aimed to revitalize Black housing and business in Starr Hill. At the heart of the plan that was developed in 2019—itself a master class in holistic urban development—is an ingenious reimagination of City Yard, a 10-acre piece of city-owned land, as a mixed-use residential and commercial area. It’s a perfect illustration of entrepreneurial spirit: transforming a municipal storage site into the heart of a revivified Vinegar Hill.

The coming of the pandemic in 2020 forced Harrell and New Hill to turn their creativity and resourcefulness back on themselves. They completed their Starr Hill Vision Plan—and, as of last November, saw it officially incorporated into Charlottesville’s Comprehensive Plan—but knew that it would be impossible, with the inevitable redirection of resources and energy, to enact it immediately. What would they do in the meantime? “People should not have to wait for generations for things to change,” Harrell says. New Hill wanted to act.

The pandemic was devastating for all business owners, but it was especially so for Black entrepreneurs. The U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Small Business reported that 41 percent of Black-owned businesses closed their doors between February and April of 2020. As New Hill worked with Black-owned businesses to stay afloat, it saw a need for a more robust network of support for Black entrepreneurs, leading to the creation of BEACON: the Black Entrepreneurial Advancement and Community Opportunity Network.

With a critical mass of Black entrepreneurs in the food industry, that’s where BEACON’s energies would be focused. And true to form, the incubator would not focus on only one area of need. In addition to training—not only general education for entrepreneurs, Harrell says, but specialized training about the food industry—BEACON will provide marketing and bookkeeping help that will enable its members to get loans and leases, access to a commercial kitchen so no one will be burdened with crippling startup costs, and even storefront space for testing new concepts and getting off the ground. The BEACON project has already begun building out training and support, and is looking for funding for kitchen and storefront spaces. “What we wanted to do,” Harrell says, “was to look at a way of helping people embrace their dream without risking their financial future: ‘I can dare to dream this dream if I want to.’”

Vinegar Hill flourished before; it is no pipe dream to think a new hill can flourish, too. If it does, it will be because of the patient, enterprising, and determined work of people like Harrell. “We want to make sure that something is happening,” she says. “We are in a position to help move lives forward in a way that the community wants to move their life forward.”