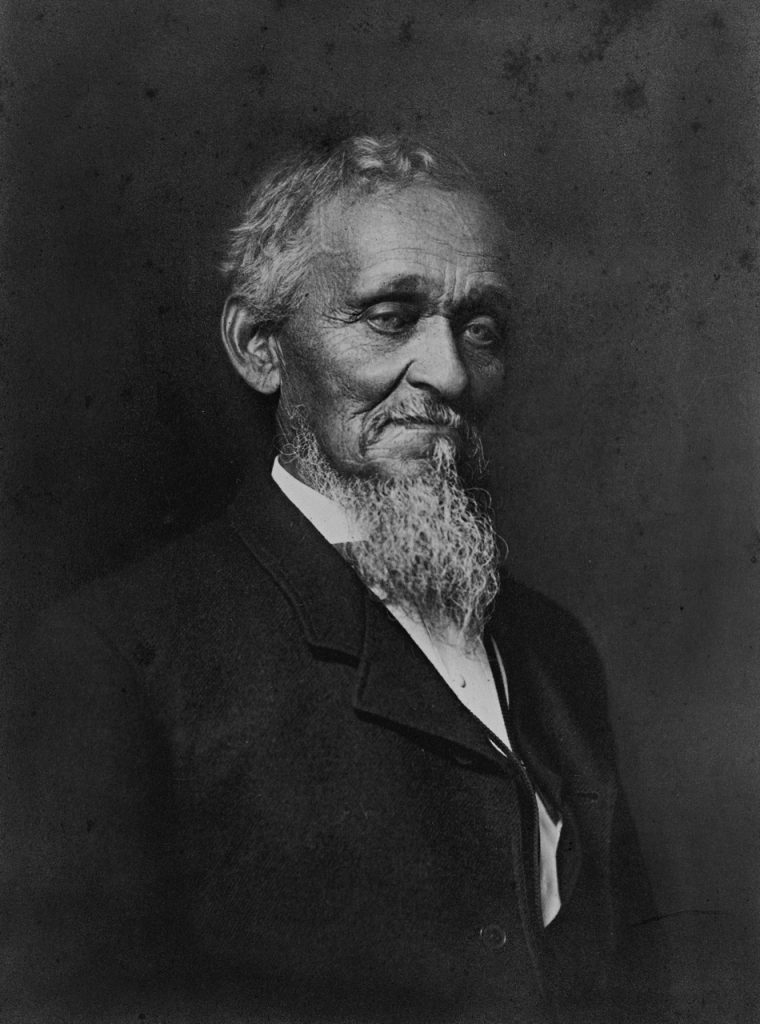

Henry Martin stands tall in the photo, his eyes piercing and thoughtful, dapper in his jacket.

Martin was born enslaved at Monticello in 1826. In the early 1900s, he was one of the most recognizable figures on Grounds. He rang the Rotunda bell, and was the head janitor at the University of Virginia. But most of the knowledge created by white people about Martin reflects their racial prejudice.

The Daily Progress wrote that Martin was a “personification of the qualities that go to make the most faithful servant.” Martin, however, was well aware of how he’d been misrepresented, so he spoke for himself through portraiture.

In the photo, part of “Visions of Progress: Portraits of Dignity, Style, and Racial Uplift,” a new exhibition at the University of Virginia’s Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library, we see a reflection of Henry Martin through his own eyes. And he is surrounded by nearly 100 portraits that similarly honor and express the personality and individual dignity of their subjects, defying a society and culture that denied them equal rights.

“Visions of Progress” features photographs produced by Charlottesville photographer Rufus Holsinger and his studio during the height of the Jim Crow era. The images, commissioned by African Americans in central Virginia, are part of an exhibition that reveals new biographical information about the subjects unearthed over the past few years by the Holsinger Studio Portrait Project team.

Holly Robertson, curator of exhibitions at the University of Virginia Library, designed “Visions” with the intention of making the portraits and their subjects “true to life.” The stories that accompany each image help to do just that.

Typical sources, like military records, birth and death certificates, and census records, wouldn’t suffice. John Edwin Mason, the exhibition’s chief curator, and his team wanted to introduce these individuals as whole people. Was Henry Smith funny? Was Cora Ross kind?

So the team asked the descendants of the individuals for help. C-VILLE Weekly documented this undertaking in 2019, as people were invited to Family Photo Day at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center to help identify the photographed individuals.

In the C-VILLE article, Mason shares that up until that point, the photographs from the Holsinger Studio Collection had not been presented in a way that represented the Black community of Charlottesville; rather, they portrayed “a very specific, very white image of Charlottesville.”

“Visions of Progress” documents the stories of the African Americans who left central Virginia and flocked to cities in the North and Midwest during the Great Migration. In doing so, the exhibition connects the local history of central Virginia to national history.

Linwood Stepp was one of those who left. Born in the Free Union district of Albemarle County to Lindsay Stepp, a blacksmith, and Jemima Stepp, a homemaker, Linwood served in France during World War I with the 349th Field Artillery.

Stepp may have commissioned his portrait as a gift to his family. Less than a year after the photo was taken, he moved to Buffalo, New York, to work at a steel mill.

He married Maggie Hansberry in Albemarle County in 1921, and the couple had three daughters.

“The magic of these portraits is that you don’t see the oppression in them,” says Mason. “And that was intentional on the part of the people who had their images made.”

Mason explains that the most attention has been paid to the oppressive side of history. “Here, we’re approaching history from a different direction.”

Though the photographs were taken during the height of the Ku Klux Klan’s violence, they do not illustrate scenes of abuse. Rather, the subjects of the portraits are dressed beautifully to resist the commonly distributed racial caricatures produced at the time.

“It’s really important that the job and status and oppression in Jim Crow are completely invisible in these pictures,” Mason says. “African Americans were not defined by their oppression.”

While the exhibition acknowledges the presence of the KKK, the effects of restrictive covenants, and the many forms of oppression endured by local African Americans at this time, the images serve as a form of silent protest against those injustices.

“They are saying, ‘We are not who you think we are. We are not those stereotypes; we are not defined by our status in Jim Crow society,’” Mason says.

This truth struck undergraduate researcher Ben Ross, too. “It’s easy to hear about the ways that the community was mistreated and oppressed and believe that they only knew hardship, but in reality this was a community full of love, dignity, and honor,” Ross says.

Rufus Holsinger—Holly to his friends—employed up to 25 people in the 1920s. Most of them took the photos included in the exhibition, yet we don’t know who they were.

Mimi Reynolds, an undergraduate research assistant who’s managing the social media accounts for the exhibition, recently posted a Holsinger photograph of Susie Lee Underwood Henderson and her child on Facebook. A little while later, Helice Jones commented that the woman and child were her Great Grandmother Susie and Aunt Evelyn.

“My hope is that the exhibition leads people to broaden their perspectives by uncovering this quiet yet powerful piece of history,” Reynolds says. Mason and library staff members urge anyone who might recognize ancestors or have any information about the portrait subjects to email the team at HolsingerStudio@virginia.edu.

The project’s website, which is currently under construction, but soon will be ready for public consumption, is a place where the team hopes people doing genealogy will download the document listing the photographed individuals and their stories, and that they’ll identify their ancestors.

This exhibition is for everyone, Mason says. Ultimately, he hopes that UVA “changes the way that everyone in central Virginia sees their history. We can tell a history of resilience, of people living complex lives in the midst of Jim Crow and living during the era of the New Negro.”

And perhaps some people will even find their ancestors brought back to life.

From the Holsinger Studio Portrait Project

Developing a clearer picture

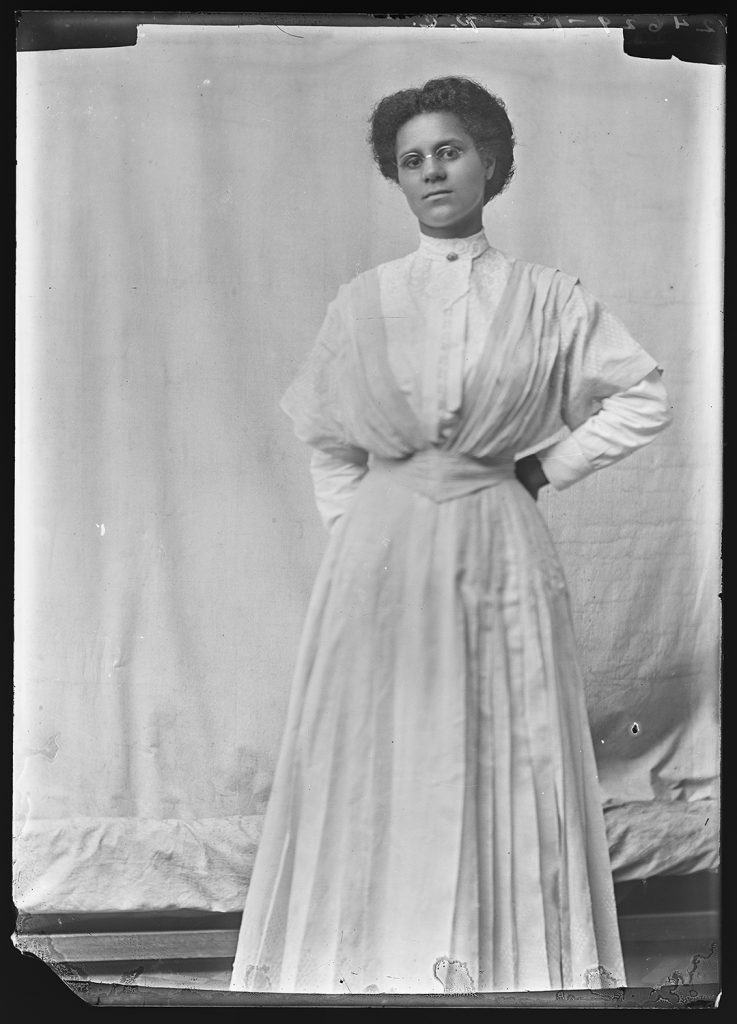

Everything about Cora Lee Ross’ (1884-1969) portrait suggests that she was an extraordinary woman—strong, proud, and wise. Her life story confirms that she faced the triple challenges of racism, sexism, and economic exploitation with an indomitable spirit.

When Ross commissioned her portrait from the Holsinger Studio, she lived in Charlottesville with her husband, James Lemuel Ross, and their five children—four girls and a boy. Cora was a housemaid, and James was a manual laborer. The couple would eventually have several more children—a daughter and two sons. Cora and James remained married until his death, in 1952.

By 1920, the family had moved to a farm in Albemarle County. James supplemented the family’s income by working as a railroad guard. Cora assumed the duties of a farm wife and mother while also working as a housemaid. Cora returned to Charlottesville in late middle-age, living in Fifeville with two of her children.

Cora’s portrait befits a woman who had the strength to raise a large family while jointly running a family farm and the style of someone with cosmopolitan tastes. Nothing about it hints that she also spent much of her adult life working as a housemaid in other families’ homes. That is precisely the point. As the University of Virginia historian Kevin Gaines has written, “[t]o publicly present one’s self … as successful, dignified, and neatly attired, constituted a transgressive refusal to occupy the subordinate status prescribed for African American men and women.”