If you’ve never heard of Martin Clark, you haven’t read The Many Aspects of Mobile Home Living, a cult classic, at least in this reporter’s book group. And you probably aren’t aware that Clark, a former circuit court judge, was the first judge in Virginia to remove from his courtroom a portrait of a Confederate general—J.E.B. Stuart—in namesake Stuart, Virginia.

Now retired, Clark, 64, has more time to write, and to speak freely, with anecdotes about Rita Mae Brown, Jay McInerney, and of course, fellow legal thriller writer John Grisham. When The Many Aspects of Mobile Home Living came out in 2000, The New York Times called Clark “the thinking man’s John Grisham, but, maybe better, the drinking man’s John Grisham.”

“I’ve never asked him about ‘the thinking man’s John Grisham,’ which I’ve dined out on for years,” says Clark in a phone interview from Stuart. He’s a big fan of Grisham, and says that people tend to discount how talented he is, and how hard it is to write a “strong, compelling muscular story” every year.

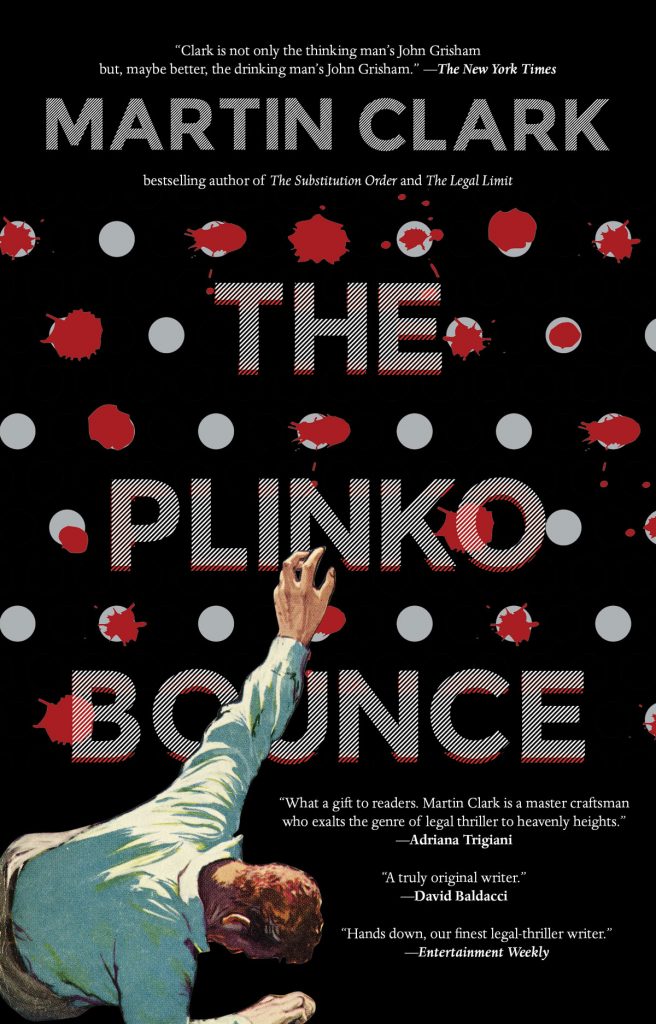

Clark describes himself as a “slow pen,” and has just released his sixth novel, The Plinko Bounce. Corruption, fraud, and behind-the-scenes manipulation are common devices in legal thrillers, including his own, says Clark. However, he’s a big believer in the integrity of the legal system, and wanted to tell a story in which there’s no corruption, but because of a legal technicality or constitutional issue, “we get an outcome that doesn’t track.”

In the case of The Plinko Bounce, a confessed murderer and all-round reprobate may walk. “So many people believe the legal system is corrupt,” says the former judge, who spent nearly three decades on the bench and who received the Virginia State Bar’s Henry Carrico Professionalism Award in 2018. “It’s not corrupt when you get a decision that’s controversial. It’s a good system that works 99 percent of the time.”

Clark grew up in Stuart, in Patrick County, where all his novels are set, and after schooling at Woodberry Forest, Davidson, and UVA law school, he returned to practice law, and became the state’s youngest judge when he was appointed at age 32.

But writing was always his first career choice, and he has 20 years of sometimes “hysterical” rejection letters before he got published. His favorite came from Rita Mae Brown. During those long years, he decided it would be “genius” to get a literary sponsor, and one night with a friend, put an early Many Aspects of Mobile Home Living manuscript in Nelson County resident Brown’s mailbox, along with a bottle of scotch.

Three weeks later, she replied: “It occurs to me you’ll either be a half-assed lawyer or a half-assed writer, because writing is a full-time profession.”

“I got good vibes from that rejection letter,” he recalls.

The vibes weren’t so good when he removed Stuart’s portrait in 2015, a year before Charlottesville began to grapple with its own Confederate iconography issue. “It was the right thing to do,” he declares, calling it a “no-brainer,“ both legally and morally.

“That decision remains unpopular where I live and I remain a villain to many people in the community.” He points to other unpopular decisions—women’s and African Americans’ right to vote, gay marriage—that were also the right thing to do.

The day after January 6, 2021, Clark, a self-proclaimed “Barry Goldwater/Bill Buckley conservative,” wrote an open letter to his congressman, Morgan Griffith, also a lawyer, scolding him for supporting Trump’s false claims that the election was stolen: “Your feckless, self-serving actions in Congress have given vitality to a dreadful lie, and in doing so, you have damaged a bedrock institution in our country, the court system… Succinctly put, you have invited people to disregard the rule of law simply because they disagree with it. We got a nice dose of that yesterday in Washington. I am ashamed of you.”

“I could do that now that I’m retired,” says Clark.

Clark was so desperate to get The Many Aspects of Mobile Home Living published that he promised God he’d give all the proceeds to his church. Stuart Presbyterian has been the beneficiary of that book’s proceeds, a pledge Clark says he didn’t dare go back on.

The protagonist in Many Aspects is also a judge, albeit a heavy drinking, pot smoking jurist. Clark says many people showed up to his readings expecting the “fun, free-wheeling Judge Evers Wheeling,” not a “buttoned up, boring judge.”

Publisher Alfred Knopf sent Clark on his first book tour with Jay McInerney, author of the cocaine-fueled Bright Lights, Big City, to show him the ropes. Says Clark, McInerney was “a delight to work with,” who was very handsome, had groupies and stalkers, and who offered to let debut novelist Clark be the headliner.

At a reading in Atlanta, a camo-dressed guy informed Clark that he could tell he wasn’t a pot smoker, because “pot didn’t make you hallucinate,” recalls Clark.

“The reason I could write Many Aspects is because I live in such a small town that everybody knows me,” says Clark. “The folks who wiped my nose and tied my mittens are here. If I were a drinker and stoner, everybody would know it. There’s no way you could do my job and be Evers Wheeling.”