During the now-infamous tiki torch rally at the University of Virginia, hundreds of white supremacists marched across Grounds on the evening of August 11, 2017. Shouting racist and anti-Semitic chants like “White lives matter” and “Jews will not replace us,” the group later surrounded and attacked student counterprotesters at the Thomas Jefferson statue in front of the Rotunda, throwing lit torches, spraying pepper spray, and hurling threats and slurs.

Five years later, students who took a stand against these white supremacists are sharing their personal narratives from the deadly Unite the Right rally in a new UVA library exhibit entitled “No Unity Without Justice: Student and Community Organizing During the 2017 Summer of Hate.” Last week, the 37-item exhibit opened to the public at the Albert and Shirley Small Special Collections Library.

“It was really healing to be able to articulate a lot of things that I had been journaling about, [and] processing on my own and with fellow survivors and students over the past couple of years,” says co-curator and UVA alumna Hannah Russell-Hunter, who was a student counterprotester at the August 11 rally.

Kendall King, a fellow UVA alumna and community organizer, first approached Russell-Hunter about creating the exhibit in 2019, but the pandemic forced them to put the project on hold until this year. In partnership with Jalane Schmidt, the UVA Democracy Initiative’s Memory Project director, King worked with guest alumni curators Russell-Hunter and Natalie Romero, as well as Memory Project postdoctoral fellow Gillet Rosenblith, to collect personal artifacts from student and community counterprotesters, including: a shoulder bag used by an activist as a shield on August 11, a tear gas canister launched at counterprotesters during the August 12 rally, and activist Emily Gorcenski’s dossier—which she provided to Charlottesville leadership before the rallies—detailing violent threats made online by Unite the Right organizers and attendees. Throughout the curation process, the alumni consulted with and gathered input from community members.

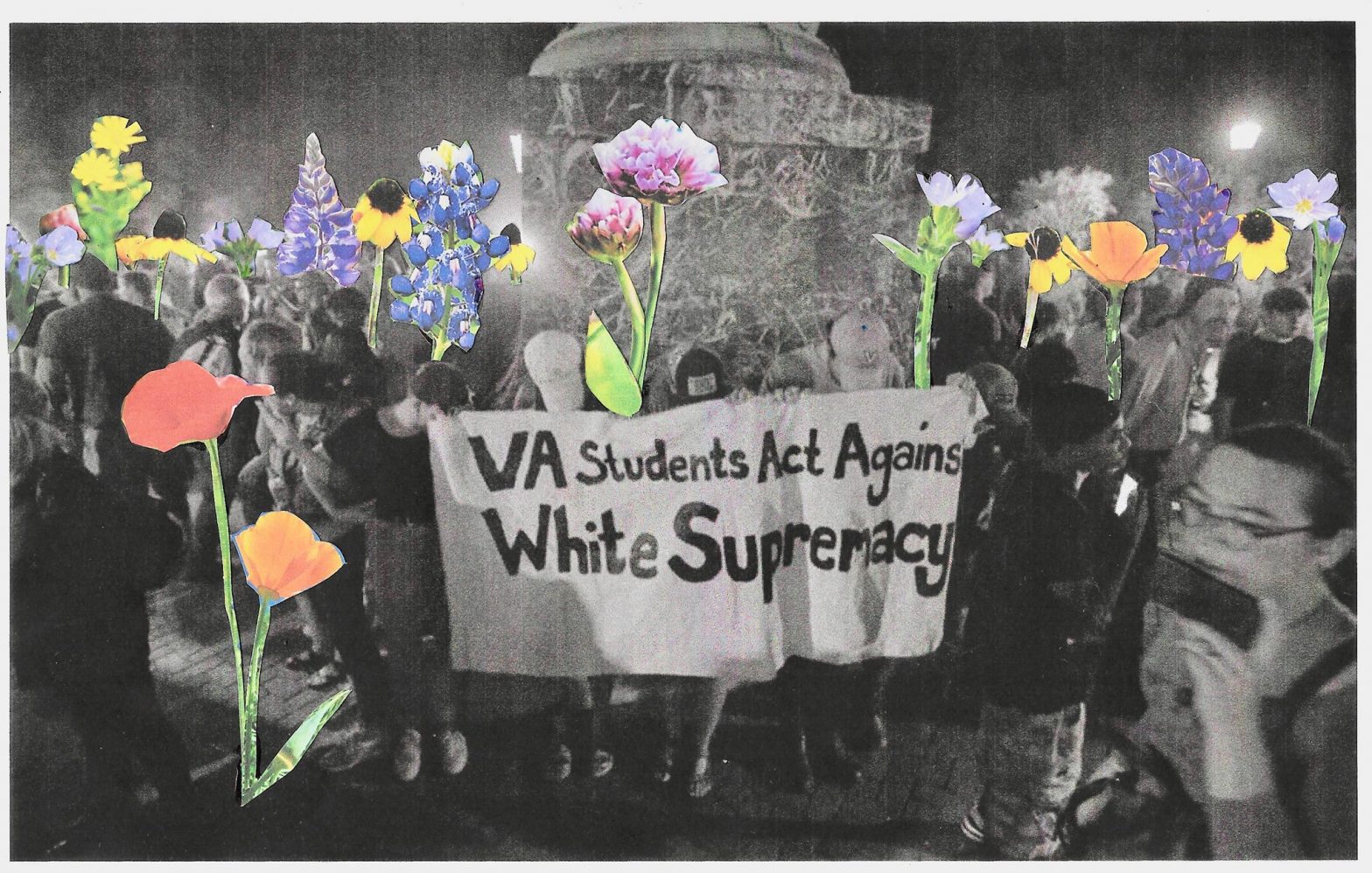

Particularly moving to Russell-Hunter is a photo of student counterprotesters holding a banner that says “VA Students Act Against White Supremacy,” while they’re surrounded by white supremacists during the torch-lit rally. On the first anniversary of the rally, she created a collage of flowers and placed them over the white supremacists in the photo, symbolizing activists’ efforts to deplatform white supremacy.

“Not only are we resisting neo-Nazis and white supremacists … [but] we’re trying to build a world where there are no neo-Nazis and white supremacists,” she says. “[And] where there is going to be no future Unite the Right rally 2.0.”

Other Summer of Hate artifacts on display include Russell-Hunter’s original draft of UVA Students United’s demands to the university, as well as her notes from a meeting student activists had with former UVA president Teresa Sullivan following the Unite the Right rally. The exhibit also features a controversial video of Sullivan claiming that no one told the university administration about the tiki torch march. (A 2017 report by former university counsel Tim Heaphy found that the university administration was warned of the impending violence, and did not properly prepare for and respond to the march.)

The exhibit also details the decades-long history of student activism at UVA—including the fight for desegregation and co-education—and criticizes the university, city leadership, and police for not taking action against rally organizers or preventing the violent events. To provide further historical context and background, the exhibit includes QR codes linking to news articles, City Council meeting minutes, the Sines v. Kessler civil lawsuit, and other important sources.

As the fifth anniversary of the rally heightened the nationwide focus on Charlottesville, Russell-Hunter believes it’s especially critical to uplift survivor and organizer voices, and reflect on what has—and hasn’t—changed in the city since 2017. She hopes visitors will come away from the exhibit with an increased recognition and appreciation of “the rich history of organizing” at UVA and in the community, she says.

“I hope that this is a starting point for more research and curiosity about the city, the [rally], and all of the circumstances around it,” adds Russell-Hunter. “We have such a deeper history to learn from.”

“No Unity Without Justice” will be on display until October 29.