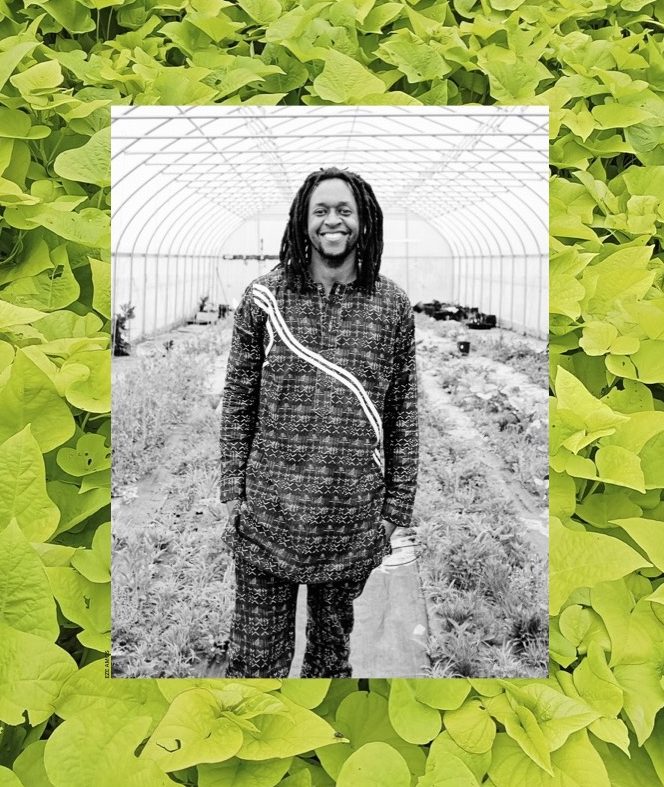

To call Michael Carter, Jr. a farmer would just barely scratch the surface. He does raise crops, but mostly what he grows are connections—to history, to other Black farmers, to markets and opportunities. It’s all encompassed in the term Africulture, also the name of the nonprofit he heads. Sitting in a farmhouse in Orange County, on land his family has owned since 1910, he begins his story by connecting the present moment back to events that took place decades ago.

The land had gone into probate and nearly left family hands, but during the 1940s, Carter’s great-grandmother and her children committed to paying off the debt. “Her three oldest sons were drafted to go into World War II, and they all sent back $29 a month Army pay for two to three years,” he explains. “And her daughters worked as domestics.” They pooled their income and saved the land. “She wanted to make sure she had a place for her boys to come back to and call home,” he says. “It really came close to us not being able to sit here [today].”

It’s not just this visit from a reporter that might never have happened; in a very roundabout way, Carter’s entire life’s work seems to flow from this land.

Surrounded by relatives who farmed and taught agriculture, he says he was “inundated” with the subject as he grew up, but resisted joining the tradition. “I wanted to be an investment banker or a street cop,” he says. “I was in 4-H and FFA and never found it attractive because I never saw Black people in those activities. As I got older the racial bias and cultural differences become much more glaring. There’s guys walking through with Confederate flags on their belt buckles. I stopped participating.”

Yet he majored in agricultural economics in college and, after becoming an African Hebrew Israelite in 2003, found himself farming on an Israeli kibbutz. Growing food took on spiritual importance.

“One of the first things in Genesis, Adam is placed in a garden, aka a farm, and he’s given instructions to till and keep the garden,” Carter says. “That gave me a different type of outlook on agriculture” as an honored, ancient occupation.

More travels followed: to Kenya and especially to Ghana, where he lived for five years in the mid-2010s, working on various agriculture initiatives—like helping conventional farmers transition to organic methods. Living in Ghana’s capital, Accra, he began supplying familiar American vegetables to the African American expat community there—things like kale, broccoli, and lettuce. Though growing those crops was a challenge in the Ghanaian climate, the project “planted a seed of creating a niche,” matching specific foods to specific customers. Yet he still wasn’t connecting all these experiences to his family legacy. “I could not see the foundation I was standing on.”

Then, in July 2017, something changed. Carter was home in Virginia for a visit, intending to go back to Ghana, but his father had begun to press him to take over the family operation. At a cookout with his relatives here on the farm, he says, “The land started speaking to me.” Reveling in family camaraderie—and seeing his four sons on the land that his ancestors had sacrificed for—awakened a connection. Even in the days when legal barriers and the KKK tried to put Black land ownership out of reach, Carter’s family had held onto these fields and woods. Now, he felt it was time for him to take up the reins. By September, he’d relocated his family to Virginia, and in November, he founded a new business called Carter Farms.

“I contacted the owner of a restaurant in D.C. called Swahili Village,” he remembers, “and inquired about growing managu”—a leafy green that’s eaten in Africa. “We’re in the second largest area of African immigrants in the country, the D.C. metro area. [Those immigrants] usually don’t have access to their traditional foods. I did some more market research and found 15 African grocery stores between Fredericksburg and Alexandria. [I said,] ‘Uh oh, that’s a market.’” He started selling crops like managu and taro leaf wholesale, and found he couldn’t keep up with the demand. “I would take stuff to [the stores] and before I got to 95 from Route 1, they called and said they sold out. It was exciting but frustrating.”

Meanwhile, he began to think about a broader mission. “Carter Farms pivoted to growing farmers versus growing produce,” he explains. “We structured Carter Farms to be much more of a business that also farms. We received a beginning farmers grant in 2019 to help out farmers as an incubator and have grown that ever since.” His focus became the larger community of African American farmers. In 2020 he founded Africulture, a nonprofit arm that supports farmers and promotes the history and culture around Black farmers and African crops.

He had already been involved in getting Black farmers connected to customers—including a big one: Aramark, the contractor that services UVA Dining. Aramark’s regional vice president, Matt Rogers, says he met Carter in 2018 through a partnership with the Local Food Hub and 4P, organizations that do support work for local farmers. “We were starting conversations about how to improve our local supply chain purchases and understanding what the barriers are,” Rogers says. Carter became a voice for BIPOC farmers—a group that Aramark, in conversation with UVA’s Working Food Group, had targeted for greater spending.

“This is a demographic that has been well underserved and is a little bit distrusting of large institutional food systems,” Rogers says. “He is of that community and they trust him.” The barriers for small farmers can be as simple as where to park on UVA Grounds when making a produce delivery.

But Carter says he was concerned about the financials, too. “You need to pay a retail price but buy a wholesale volume,” he remembers telling Aramark. “I’m dealing with vegetable farmers, not commodity farmers that can make up for their low margins with volume.” He saw the African vegetables he’d been encouraging farmers to grow as a niche with both economic and cultural value: “We’re going to be growing some things you can’t get anywhere else.” If there was nutritional and educational benefit to Aramark serving ingredients like Nigerian spinach or callaloo, then Black farmers growing those crops could earn a premium.

Carter secured promises from Aramark to pay well and help out with the food safety certification process, which can be burdensome for small growers. The company also offers up-front guarantees to buy farmers’ produce. “I was shocked they had come to this,” Carter says frankly.

His approach wasn’t just to make demands. He also tried to get people excited. “The [Aramark] chefs came out here [to the farm], and we provided them some ethnic vegetables,” he says. “The chefs were inspired and started to create recipes.” He in turn went to UVA to give a presentation about the ingredients, sending students home with recipe cards in their pockets.

One of the crops Carter highlights is already familiar in the U.S.: good old sweet potatoes. But he’s been spreading the word that the leaves, not just the tubers, are delicious and full of nutrients.

It was news to Clif Slade, one of the many Black farmers in Carter’s network. Slade is a third-generation farmer who grows sweet potatoes on 15 acres in Surry County. For years, he’s been selling “slips”—baby sweet potato plants that other gardeners transplant into their plots in spring. He ships half a million of these around the U.S. every year between May and July, but he’d never considered the leaves to be a crop in their own right.

“I have an acre of plants that basically is worthless come July 15; I can’t sell them anymore,” he explains. “In comes Michael Carter and he says ‘Let’s see if we can sell them.’ We cooked [the greens] and they were very delicious. If it can turn lucrative, we can have these sweet potato greens right on up to Christmas.”

He says that Carter’s marketing savvy adds something important to his operation. “Mike’s a very enterprising young man,” he says. “This is like a byproduct, but it’s very scrumptious. I’m more of a grower than a marketer, and I’m 69 years old. He knows how to use all the social media. If it wasn’t for Mike I wouldn’t even try this.” He’s exploring the possibility of supplying both UVA and William & Mary with sweet potato greens, and says that Carter has plans for a public event at Slade Farms with food trucks and chefs.

According to Rogers, Aramark is already buying from eight or nine BIPOC farmers to supply UVA Dining. It took a few years to get there. “That was fall last year, really having this thing off the ground,” Rogers says. “Everything to that point was more capacity-building.”

Meanwhile, Carter continues to expand the scope of his mission. He sees his support of Black farmers as the preservation of an endangered way of life. “In 1925 in the state of Virginia, there were approximately 50 to 52,000 Black farmers,” he says. “[By] 2017 there were 1,333 Black farmers. That’s a 98 percent decline. This is an extinction-level event. In any situation where you have extinction you have to change the environment. I’ve sought to change the environment.”

As ever, that means attending to culture as much as to the business side. “I learned in Ghana that everything is connected,” he says. He keeps on finding more links: between the African-derived banjo and the gourds it can be made from; between young kids of color and the natural world; between American weeds and the African plants they sometimes resemble. The farm continues to act as a base for Carter to share these moments of expansion with all kinds of visitors. “When people leave here I want them to leave full, not with bellies, but with knowledge and soul being full,” he says.

Carter is teaching an Africulture course at UVA—bringing the connections to an audience on Grounds, even at a moment when diversity initiatives at the school are under attack. “I never expected someone would ask me to consult with a major corporation or teach at a university,” he says.

“I don’t claim to be an overly great farmer in terms of produce, but I grow farmers. And my greatest commodity is my story.”

Now growing

At Carter Farms, Michael Carter, Jr. plants many vegetables that are native to Africa, and are popular ingredients for immigrant communities in Virginia.

Managu

Common in Kenya and surrounding regions, managu leaves are often cooked with other greens.

Taro Leaf

Poisonous before cooking, the leaves of the taro plant are a staple in Africa and Asia.

Nigerian Spinach

This is an African green that’s used in soups and stews in many countries across the continent.

Callaloo

A rich leafy green that is frequently made into a popular Caribbean dish of the same name.

Sweet Potato Greens

The classic sweet tuber’s leaves have plenty of nutrients and flavor.