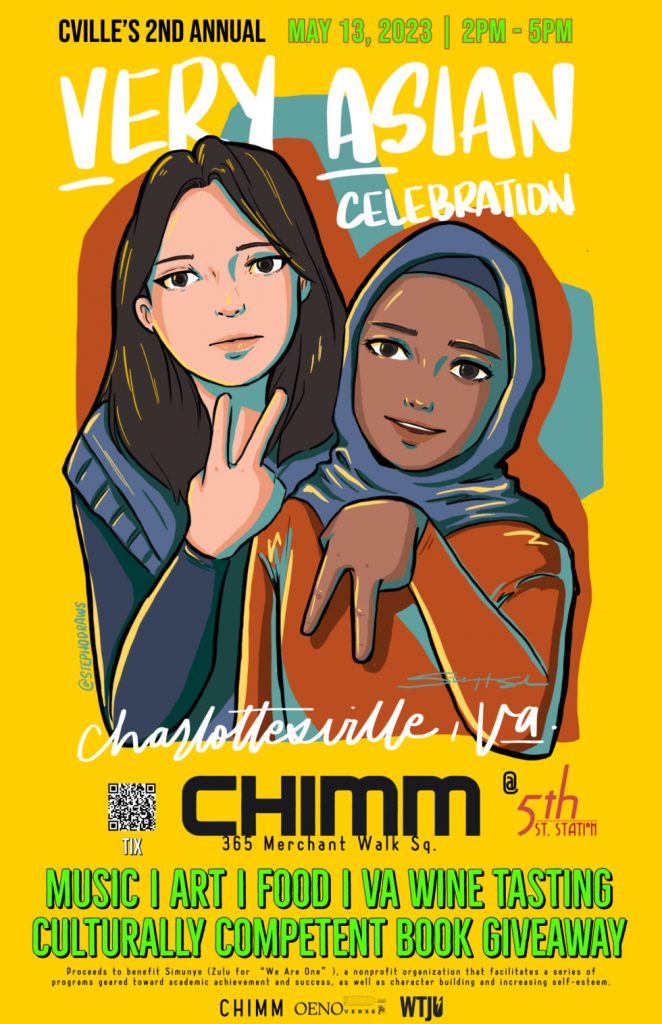

In celebration of Asian Pacific American Heritage Month, the second annual VeryAsian celebration is coming to 5th Street Station on May 13. The day-long event, co-organized by Jay Pun and Sylvia Chong, is jam-packed with music, art, food, and community. Chong, a professor and director of the minor in Asian Pacific American Studies at UVA, discusses the history of APAHM, the importance of VeryAsian, and her performance of Asian American folk rock as part of the celebration. veryasianva.com

What is Asian Pacific American Heritage Month?

It’s a chance to celebrate and honor the histories and cultures of Asians and Pacific Islanders in the U.S.

Is there any significance to it being held during the month of May?

It honors two historical events: May 7, 1943, marks the arrival of the first Japanese American immigrant, a 14-year-old sailor named Manjiro, and May 10, 1896, saw the completion of the first Transcontinental Railroad, on which over 12,000 Chinese had labored.

Charlottesville, and UVA, certainly have a long, largely unacknowledged, history of racism toward Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. And more recently, the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic led to many people of Asian descent being targeted by hate crimes. How does our local history fit into broader experiences?

Sadly, many people are unaware of how Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders contributed to the building of this nation, from the Transcontinental Railroad and the sugar cane plantations of Hawai’i to military veterans from the civil war up to the war in Afghanistan. A lot of anti-Asian racism presumes that Asians are foreign, culturally deficient, and conduits of disease or immorality, that Pacific Islanders are primitive, and that all of them are interchangeable. When I researched the first Asian students at UVA in the early 1900s, I found stories by their white classmates ridiculing Chinese and Japanese as heathen, grotesque, and ignorant, despite the fact that many of these students were highly educated, fluent in English, and often Christian. There’s a direct line between this and the recent spate of anti-Asian violence, which presumed that Asian Americans were responsible for bringing COVID to the U.S., or the Atlanta spa shootings, in which the murderer blamed his sex addiction on Asian massage workers.

Last year’s APAHM fest was the first of its kind in Charlottesville. What does it mean to bring this celebration to the city at this time?

Asian American students at UVA have a decades-long tradition of celebrating APAHM with dozens of events, but outside the university, there was almost nothing going on. During the isolation of the pandemic and the frightening rise in anti-Asian violence, I started talking with my friend and co-organizer Jay Pun, who grew up in Charlottesville, about what we could do to respond to this. We threw together the first Charlottesville APAHM celebration in just under a month, focusing on the diverse artistic expression and experiences of Asian Americans, from recent immigrants to those born here, from adoptees to mixed-race folks. Our event was a way of taking up space, of showing up and speaking up.

Together, Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders make an incredibly broad group. How is VeryAsian celebrating AAPI voices and stories?

Jay got inspired by the St. Louis news anchor Michelle Li, who got racist messages about being “very Asian” when she tried to talk about eating Korean food on New Year’s. That’s why our festival is named “Very Asian” this year—we’re focusing on the different ways we may claim our Asian Americanness, from food to music to art. Although some of this may seem traditionally Asian, a lot of the festival will draw on the ways we’ve created new identities in the U.S. that are unique and different even from one another. We’ve also tried to highlight the enormous diversity within Asian America. People assume Asian means Chinese or Japanese, but we also have participants with Thai, Filipino, Indian, Bangladeshi, Pakistani, and Korean heritage.

In addition to co-organizing VeryAsian, you’re also performing Asian American folk rock. What is Asian American music to you?

I ask myself and my students this question a lot. Again, many people think Asian American music is Asian music, and usually only traditional music. But what about Asian American jazz, rap, folk, or rock? In my set, I include two songs from the Asian American movement in the 1970s by singer-activists Chris Iijima and Nobuko Miyamoto. They are influenced by Woody Guthrie, Jefferson Airplane, and Nina Simone, but they sing about things like imperialism, the Vietnam War and the Japanese American incarceration. I also do a song by the Khmer American band Dengue Fever, which was part of a pandemic-era hashtag (#CRBChallenge, for the play “Cambodian Rock Band”), not only to support Asian American theaters, but also to address systemic racism and anti-Blackness. Of course, there’s a wide world of Asian American hip-hop that I can’t begin to cover with my limited abilities, so I urge folks to check out Ruby Ibarra, the Far East Movement, and M.I.A. if you’re interested.