Rod Walker has always loved the natural world. Throughout his career as an IT consultant, the avid hunter and fisherman owned forested land where he and his family could get away for a quieter life, if only for a weekend. But now retired to a western Albemarle County farm, his quiet life has inspired a new crusade: He’s one of the generals in the war against invasive plants that threaten our forests and fields.

In the mid-1990s, planning ahead for retirement, Midwesterners Walker and his wife Maggie went looking for land. “We had this theory—buy now and be ahead of the baby boomer rush,” he recalls. They had four must-haves: at least 50 acres, close to culture, good health care, and an airport. After two years of searching, the Walkers found their place—1,500 acres near Sugar Hollow. Over the next few years, the couple designed and built a new home on a ridge overlooking their valley, using stone from their mountainside and wood from their own trees. They moved in for good in 2012.

With a large chuck of forest to care for—“never in my wildest dreams did I think we’d end up with 1,500 acres”—Walker hired a forestry consultant to develop a management plan. His priorities included a healthy forest with plenty of wildlife, and careful harvesting to maintain forest health and generate money to help cover the costs.

During that process, Walker enrolled to be certified as a tree farmer. (Certification under the American Tree Farm System is open to anyone who owns 10 to 10,000 acres of forested land). The ATFS encourages landowners to apply the best management practices to their forests, and creates a network of common-minded conservationists. According to an ATFS member survey, “The top three objectives of family forest owners in the program are conserving wildlife habitat, having a place to enjoy with their friends and families, and leaving the land better for the next generations.”

The forest management survey of the Walkers’ land found many beauties—and lots of threats. Walker recalls early on, when they saw “these little vines with red berries, we thought they were native. Fast forward 15 years, and we found 15 acres close to Shenandoah National Park that were just a wall of these vines. We had to use a bulldozer to get into that area and start clearing it.” That was his introduction to Oriental bittersweet, one of the area’s most common invasive species.

Because their land abuts Shenandoah National Park, the Walkers contacted Jake Hughes, a park biologist specializing in invasive plant management and forest restoration. From Hughes, they learned about Cooperative Weed Management Areas, a collaboration of government agencies, groups, and private landowners working together to control invasive species. There were plenty of CWMAs around the country, but none in Virginia. In 2013, Walker began talking with other agencies and groups, and the Shenandoah National Park Trust agreed to be the new organization’s 501(c)(3) sponsor and provide administrative support.

That was the start of Blue Ridge PRISM—the Partnership for Regional Invasive Species Management. “We started with the western half of Albemarle County,” Walker recalls, “and then we figured, hey, go big or go home.” PRISM expanded to cover the 10 counties surrounding the national park, and last year it added Loudoun and Fauquier counties. In 2020, it set up its own NGO independent of the SNP Trust.

Hughes, who is still actively involved with PRISM’s leadership team and its advisory council, says, “The bulk of interest [in starting PRISM] came from private landowners. They really drove it. And PRISM has done a fantastic job on landowner education, and on helping with [public] awareness.”

Walker says PRISM is “unusual [among CWMAs] in that we don’t just work on the land of our members—we focus on the education of everyone.” While large landowners and commercial operations like farms, orchards, and wineries pay attention to the threat of invasive plants because of its economic impact, managing the problem area-wide requires the participation of landowners of all sizes. As Walker points out, invasives do not respect boundaries.

Walt Morgan, who bought eight acres along the north Rivanna River in 2019, is one of the local small landholders who has benefited from PRISM’s efforts. A transplant from the West Coast, Morgan was used to a much drier climate. At first, he was delighted by how green his property was—until he realized all that green was actually vines pulling his trees down.

PRISM’s resources and activities helped him get educated about his invasives and how to manage them. “I’m learning to see the whole ecology here,” Morgan says. “This has been a really positive experience; there are a lot of people in this area really working to be stewards of the land.”

Jennifer Gagnon, coordinator of the Virginia Forest Landowner Education Program, calls Blue Ridge PRISM “a fantastic resource” for landowners large and small across the state, adding that “we rely on them in the Shenandoah area.” She finds invasives to be “the number one concern” among the landowners she works with, so there’s a link to the PRISM website in her program’s monthly newsletter. In fact, it was Gagnon who nominated Walker for his recent recognition as ATFS’s 2023 Virginia Tree Farmer of the Year.

While education was and is PRISM’s primary focus, Walker says, “Soon we saw we needed a second thrust on policy, with Richmond and the state agencies.” One of its first efforts was expanding the state’s noxious weed list, developed by Virginia’s Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services. The list now includes 14 species: “Half of [them] we worked to have added, and 12 more are in the regulatory approval process.”

When PRISM first started focusing on policy, Virginia law said plants that were “widely disseminated” (i.e., occurring in many places around the state) couldn’t be added to the state’s noxious weeds list. PRISM and its partners worked out a compromise with the nursery industry, says Walker, and got the law changed so that only plants commercially propagated in Virginia could be exempted.

PRISM’s most recent success was pushing for a bill stipulating that the state’s invasive plant species list, published by the Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation (not the same as the noxious weeds list), must be updated every four years. It also requires landscape architects, landscape designers, and landscapers to inform landowners if any plants they are specifying are on the list. “Most of the plants grown in Virginia nurseries are sold wholesale,” Walker says, so getting to landscaping professionals is another way of educating homeowners and giving them a choice before something is planted on their property.

Walker says that PRISM’s efforts have gotten a huge boost from the native plants movement, which encourages people to plant flowers, shrubs, grasses, and trees that have evolved to fit our area’s climate, soil types, and wildlife. Local herbivores—like deer and rabbits—may steer clear of non-natives, so the native plants get overgrazed, which allows the invasives to take over. The fruits of non-native species may not provide local birds with the nutrition they need for migrating or wintering over. And many non-native species aren’t good hosts or food sources for local beneficial insects, affecting everything from pollinators to caterpillars.

One of PRISM’s current efforts is trying to get the state to enact incentives for clearing invasives and planting native species. North Carolina, Walker notes, enacted a Bradford pear bounty: Remove one of these invasive trees, get a native replacement free. PRISM also has proposals under consideration at Virginia Tech for studies quantifying the economic cost of controlling invasives and forecasting their impact in the state—useful data for shaping policy in Richmond.

Another effort is the statewide conference PRISM will hold in December, inviting government agencies and nonprofits from around the commonwealth to identify the biggest problem areas in the state and develop proposals to suppress invasives there. Walker hopes that Blue Ridge PRISM’s example will spur the formation of other CWMAs around the state, in conjunction with the efforts of nonprofits like the Chesapeake Bay Foundation, The Nature Conservancy, and the Virginia Native Plant Society as well as the state agencies that deal with land and wildlife.

Walker is heartened by the increasing public awareness about invasive species—PRISM’s email newsletter’s circulation has increased fivefold since 2018. “The word is getting out,” he says, “in part because the problem is getting worse. If climate change wasn’t happening, we’d still have this problem—but it does make [the impact of invasives] worse.”

That’s why PRISM concentrates on education of the general public, of large landowners, and of anyone who has a yard. “If you have an acre, you can keep it clear of invasives on your own,” Walker says—with the help of PRISM and a little sweat equity.

Among other ways to support PRISM’s work, you can raise a glass to its efforts, on September 23, with an educational session and fundraiser at Devils Backbone Base Camp in Nelson County. Every glass of Vienna Lager sold supports PRISM’s war against invasive plants.

Identifying invaders

Non-native plants have been arriving for centuries, and many of them have become part of the landscape—think tiger daylilies, forsythia, and daffodils. Non-native species only become invasive when they are both rampant propagators (e.g., put out huge amounts of seeds or send out large root networks) and hard to contain, usually because there are no natural control mechanisms like predators, diseases, or insects. As a result, native species are out-competed—or overwhelmed. Oriental bittersweet and porcelain berry, for example, climb over trees and shut out access to sunlight, and their added weight can cause trees to crack or fall.

Some native species, like wild grape and poison ivy, can be categorized as aggressive. But usually there are native creatures that help keep them under control. (In many areas, for example, deer prefer browsing on poison ivy.)

As for the idea that invasive plants are only a problem on land that has been disturbed, Walker points out “almost none of Virginia is undisturbed” due to centuries of farming and development.

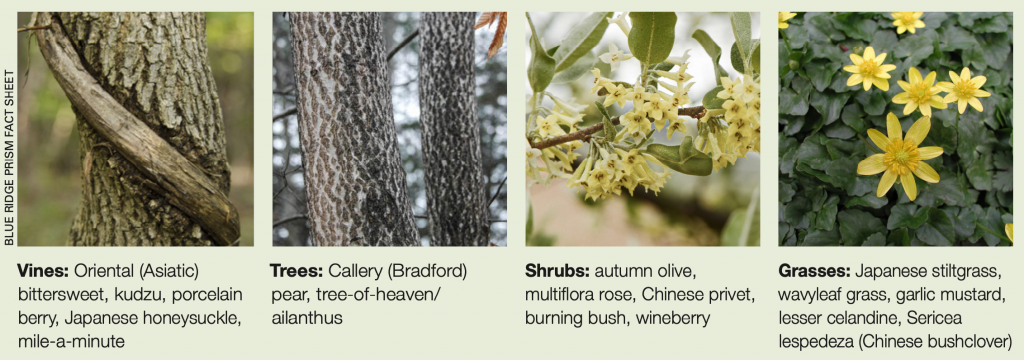

Blue Ridge PRISM’s list of the biggest threats in our area

Joining the fight

Get educated. Find out what’s growing on your property. There are plenty of resources—government agencies, universities, and nonprofits like PRISM—that provide fact sheets, online resources, and educational sessions to help you identify problem plants.

Report what you find. PRISM participates in the Virginia Invasive Mapping Initiative, a state-wide effort to collect data on species occurrence and spread to aid in policy-making and control efforts. Anyone can support the initiative by using an app called EDDMapS to document where invasives are on the rise.

Fight invasives. Resources like PRISM, Virginia Tech’s Cooperative Extension Service, and the Virginia Department of Forestry can provide information on the best way to attack specific problem plants: how and when to prune, how and when to safely use pesticides when necessary. Many invasives, once established, are almost impossible to eradicate, but they can be controlled.

Plant native species. We all have favorite plants (native or not), but choosing species that have evolved to flourish in this area not only helps control invasives, but also benefits native birds, beneficial insects, and pollinators—and your neighbors. After all, many invasives are garden plants that escaped.

Learn more about our environment. The forests that make us love living here are under attack by other factors—climate change, new diseases, invasive insects. Native wildlife too is also threatened by these factors, as well as by development and human overuse. This area is getting more popular—and more populous—every year. Each one of us has an impact, and we all can do something to protect this place.