UVA Medical Center has sued more than 30,000 people over unpaid bills since 2010. One woman is pushing back.

Cancer. Major surgery. An uncertain prognosis.

It’s a nightmare situation no matter how you look at it. But when Zann Nelson got the phone call nobody wants to get in 2012—a UVA nurse practitioner telling her the tests she’d just gone through came back positive for uterine cancer—her vantage point was especially bleak. She didn’t have health insurance.

The cost of the operation she got at her surgeon’s urging despite her fears about being unable to pay wasn’t necessarily catastrophic—it cost about as much as a new compact car—but it might ruin her financially anyway. Like tens of thousands of other locals in the last several years, she found herself on the receiving end of a civil suit brought by UVA over medical bills. Unlike most, she chose to fight the claim in court—by herself.

“I’m not trying to push the responsibility off on anyone else,” Nelson said. “I never wanted to be pitied. I want to pay my bill.” She claims she was never told how much she’d owe, and that she felt taken advantage of when she was at her most vulnerable and was dismissed when she tried to work with the hospital. So she’s taking a stand.

It’s an unusual case, and one that brings up serious questions for the University’s medical center, which, like other public hospitals, is facing a future of major shortfalls as it struggles to fund its mandate to care for all patients, regardless of their ability to pay: Should care providers consider financial impact an essential part of the health care equation? And should a public hospital sue its way to a secure bottom line?

Bad timing

Zann Nelson describes her life as one of ups and downs, but mostly—thanks to thrift and hard work—ups. She brought up her two children on the Culpeper farm her father, a Pan-Am pilot who spent his boyhood on a Texas ranch, bought for his family in 1951. She raised cattle and trained horses, hung on to the land through a divorce, and found work as the director of a local nonprofit museum. Then came tragedy and hardship: Her son took his own life in 2003, just shy of his 18th birthday. Her second husband, who had been unemployed since 2001, left the following year, saddling her with heavy debts. Two years later, she lost her job.

Still, she managed. She worked with her bank to secure what she described as a “monster” loan that let her hang onto her house, writing, consulting on preservation issues, and bringing in a little income from rental properties in order to make payments. Despite the housing crash, the plan to sell off pieces of the farm to pay down debts was working, she said, albeit slowly.

One thing that went by the wayside in the lean years, though, was health insurance. She’d paid out of pocket for a plan post-divorce, but the premiums kept climbing despite the fact that she made no claims, and she let it lapse. She was 63. She’d always been healthy. She figured she could stick it out until she was eligible for Medicare in a few more years.

Then, just over two years ago, she was in the middle of lunch with a friend when she was seized with cramps. In the bathroom, she realized she was having what looked like a heavy period—which made no sense, as she hadn’t had one for at least a decade. Her first feelings were ones of panic.

“I wanted to cry, to have someone else fix the problem, care for me,” she said. But she knew none of those were options. And even before she left the restaurant, she was worrying about how much whatever problem had just reared its head was going to cost.

She didn’t think it could end up being everything she had left.

A surgery, a suit

Nelson tried her best to master her anxiety and come up with a plan. The receptionists at the busy office of the doctor who had once been her regular gynecologist told her to go to the emergency room if she was critical. She called her nearby free clinic instead, and was told to try the free clinic in Charlottesville. They told her she couldn’t be seen for a month, and to try UVA’s Midlife Health Center—which was not, as she remembers being told, a low-cost provider for the uninsured like the clinic.

When she arrived at UVA Imaging for an ultrasound, she said she was clear about her financial situation: She didn’t have insurance, and she was worried about being able to pay. The staff there had a ready solution, detailed in a bill that’s included in Nelson’s extensive records. They offered her a 20 percent discount on her $1,150 bill for the day’s procedures and a plan with monthly payments based around what she thought she could afford.

That, she said, was the first and last straightforward conversation she had about money with her care providers.

Later the same day, at the registration desk at the Midlife Health Center where she went for a battery of tests, she asked again about cost. She was told she could file for financial assistance, but she doesn’t remember being given any other information, including a price tag for the procedures to come. It was busy. Someone handed her a small piece of paper the size of an index card to sign. She doesn’t remember that, but she knows she signed it.

She knows because it’s now labeled Exhibit B in her massive stack of court filings. Under the heading “Long Term Signature Agreement” is her name, along with the following in small type: “In consideration of services furnished or to be furnished, I guarantee payment to the Medical Center…and the Physicians Group of all outstanding balances incurred or to be incurred including those not paid by any third party source. If payment is not made when due, I agree to pay all reasonable costs and expenses related to collection of any outstanding balances, including but not limited to reasonable attorneys’ fees.”

Five days later, she got the phone call. She had Stage 1 uterine cancer. A few days after that, still reeling, she met with a surgeon at UVA’s Cancer Center, who recommended a complete hysterectomy within a month. Again, she said, she brought up her lack of insurance and her worries about the total cost.

Many months later in court, she tried to get the same surgeon to repeat the advice Nelson says she gave her in the exam room that day. The exchange, included in the trial transcript, was peppered with objections by attorney Peter Hetzel, representing UVA, and direction from Albemarle County Circuit Court Judge Cheryl Higgins.

“Did we have a conversation about my concerns of being able to pay the bills?” Nelson asked.

“I don’t recall,” the surgeon said, “but if we did—”

“Then I would object to anything further,” Hetzel interjected. “That’s the point I was making; she doesn’t recall this conversation that we are supposedly revisiting.”

Then Higgins: “The Court’s going to sustain the objection.”

“At any time, did you offer advice to me to not worry about the finances, that we needed to simply focus on my health?” Nelson went on.

“I—generally, that is what I would say, was that you can’t put a price tag on your life. This is my spiel to every patient, so I feel like I probably said it. And that I try not to think about…finances, because I so much want my decision-making to be only about my patient’s health and taking good care of them. And you know, we have a financial program that I will send patients to ask those questions because I don’t know.”

Nelson says nobody at the Cancer Center directed her to the financial counseling center. And the card with about 200 words of legalese that she’d blindly signed a few days before she got her diagnosis turned out to be the only contract for hospital care she’d ever see.

So why didn’t she press the issue? Why didn’t she keep asking about the cost of what was coming until she got an answer?

“I know at any point I could have said, ‘Stop the horses, I want to get off,’” Nelson said. But she said she was afraid to do anything other than go ahead with rapid treatment. She figured that whatever the final bill, the hospital would work with her to hammer out a payment plan she could afford, she said, just as UVA Imaging had. The fact that her doctor was recommending surgery, and quickly, despite her financial concerns, seemed to support her assumption.

“I thought I was doing the responsible thing for my health,” she said.

She had the surgery in July. In e-mail exchanges with her surgeon afterward, she learned her cancer didn’t appear to be aggressive. Her incisions healed. She was hopeful. “With all sincerity,” she wrote to the surgeon, “you have reaffirmed my faith in the medical profession.”

The bills showed up in August. The UVA Physicians Group wanted $5,573, the Medical Center $27,802.51.

“I immediately started trying to work out some kind of plan,” she said. UVA offers an across-the-board 20 percent discount for patients without insurance, she learned. But because she owned assets well-over the state-regulated threshold of $3,200, she didn’t qualify for charity care. She was told her monthly payments would still total about $1,000 a month, she said—nearly her entire monthly income.

She eventually worked out a payment schedule with the Physicians Group, but the biggest bill, owed to the Medical Center, was still outstanding, and there was no plan in place to pay it down. For months, she said, she called and wrote, trying to get a meeting with someone. Eventually, she got a face-to-face with an administrator, but she said she couldn’t negotiate her payments down to something she could manage on her limited salary.

“There wasn’t anything concrete I could work with,” said Nelson. She heard nothing more until April, when the Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia filed a civil complaint against her in Albemarle County Circuit Court for $23,849.21.

“I never thought it would be free,” she said. “I want to pay what was equitable. I’m still willing to pay.” But the monthly total was just too high. The money wasn’t there. She couldn’t afford a lawyer. She couldn’t find anyone to represent her pro bono. Her only choice, she felt, was to represent herself and fight the claim on the grounds that the contract wasn’t valid.

Charity care and collections

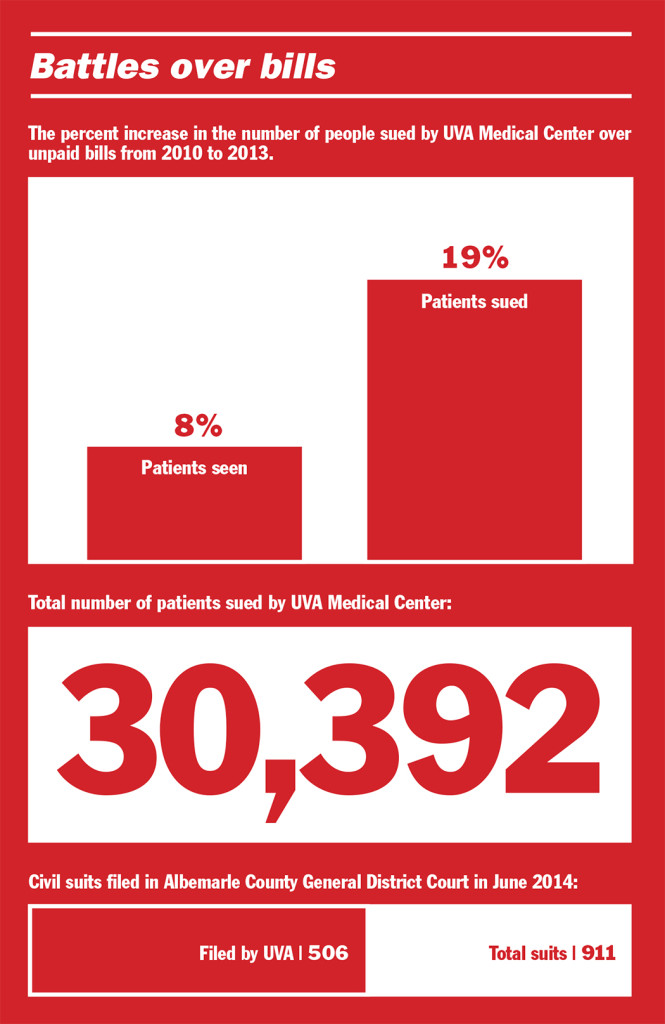

As a defendant on the receiving end of a UVA suit over medical bills, Nelson has plenty of company. According to numbers provided by Medical Center spokesman Eric Swensen, between 2010 and 2013, the hospital filed 30,392 cases against patient debtors in Albemarle County General District Court, which handles debt claims under $25,000. That’s about 4 percent of the total number of patients who came through the Medical Center in the same time period.

The number of civil cases rose more than twice as fast as the hospital’s annual patient population in those four years. A total of 6,967 cases were filed in 2010, and 8,297 in 2013—an increase of 19 percent. At the same time, the number of Medical Center patients went up just 8 percent in the same time period, from 197,643 to 213,353.

Private hospitals like Martha Jefferson can turn away patients seeking care that’s deemed not medically necessary*, but publicly supported medical centers like UVA are required to treat everyone, regardless of ability to pay. That means it’s the public hospitals that typically bear the brunt of caring for more people who struggle to pay or can’t pay at all—and that’s a lot of people. A recent study by the Urban Institute’s Health Policy Center estimated that U.S. hospitals provided $84.9 billion in uncompensated care in 2013. UVA provided $234 million in financial assistance through uncompensated charity care last year, said Swensen.

In Virginia, public hospitals are teetering on the edge of a serious financial pit. The Affordable Care Act hinges on an expansion of Medicaid to offer more insurance to more people and a simultaneous scaling back of the amount of federal funds hospitals get as compensation for indigent care. But the ACA leaves the critical decision of whether to grow Medicaid up to the states, and after a protracted budget battle that threatened to shut down Virginia’s government, the Commonwealth said no to more Medicaid. Already, UVA and Virginia Commonwealth University saw $15 million in indigent care cut from the state budget this year.

Deb Thexton, Martha Jefferson’s director of finance, said private medical centers are facing new pressures, too. Uncollected debt became a much bigger issue for all hospitals when the recession hit, and shifts in the health insurance landscape aren’t helping. “If you look at the policies that are offered on the exchange”—the health insurance marketplace set up by the ACA—“more of them are moving toward higher deductible plans, which moves the burden of the payment to the patient, and the burden of collection to the hospital,” said Thexton. There’s no question, she said, that that’s going to increase the amount of bad debt care providers are left with.

There are similarities between UVA’s approach toward care for the uninsured and Martha Jefferson’s. According to Swensen and Thexton, both hospitals offer no-interest payment plans for big bills, financial assistance for those who meet income-based charity care thresholds, a discount for all uninsured patients (Martha Jefferson’s is 42 percent to UVA’s 20), and assistance in applying for Medicaid. UVA also devotes considerable resources to helping patients sign up for Family Access to Medical Insurance Security, or FAMIS, a program that provides insurance coverage plus some reimbursement for the hospital.

UVA’s Swensen said the hospital does ask patients at registration if they expect to have trouble paying their bill; if they say yes, they’re given an information packet with a financial aid application and Web addresses and phone numbers for more information. Doctors typically don’t weigh in when it comes to costs, he said.

“Our care providers are focused more on making decisions in the best interests of each patient’s care,” he said. “We have full-time financial counselors and a centralized pricing group available to assist patients in getting more information about costs.”

Thexton described a more proactive policy at Martha Jefferson: Besides handing a billing brochure explaining payment options to every patient at registration, hospital financial aid counselors approach every uninsured patient facing a bill expected to be over $25 individually to prompt a conversation about pay. It’s not unusual now for the hospital’s doctors to field inquiries from patients about costs, she said.

“I think that role that the physician plays is beginning to evolve as more and more folks become more responsible for a bigger portion of their care,” Thexton said.

And then there’s litigation. In the month of June this year, The Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia filed 506 claims against debtors in Albemarle County District Court—more than 55 percent of the total civil claims sought by any plaintiff that month. Martha Jefferson filed none. Thexton said the number of claims filed by the hospital’s collections department fluctuations, but is often between 15 and 20 a month.

Swensen said UVA Medical Center does “everything possible” to work out a payment plan before filing a civil claim. “We view filing court cases as a last resort for collecting payment,” he said.

But local attorneys who handle medical debt cases said they’ve noticed that UVA takes a more aggressive stance towards debtors than it did 10 to 15 years ago. Yvonne Griffin is a personal injury lawyer who sometimes represents clients who are sued by the University for nonpayment of their hospital bills while waiting for insurance companies to cough up claim money after an accident.

In such cases, “they used to withhold the bills if there was a lawyer involved,” she said, but these days, it’s more common to see UVA’s lawyers file a warrant in debt instead of waiting for the insurance payout. If a judge rules in their favor, they can start garnishing a former patient’s wages in lieu of payment.

Larry Miller of Miller Law Group pointed out that UVA doesn’t have to stop there. “They’re a state agency,” he said, “so if you file your tax return for the state of Virginia and you get a refund, they can seize that.”

Because UVA, like most hospitals, includes a provision in its care contract that covers fees for the attorneys they hire to collect, there’s less incentive for them to negotiate a settlement, said Miller.

“It’s an understandable place they’re coming from,” Griffin said. UVA has to take in patients private competitors might not, including cases where reimbursement in full isn’t a given. They can’t afford to hemorrhage money when people who can pay don’t.

“Certainly as a taxpayer, that would be important to me,” Griffin said.

She and Miller said one thing is certain if you decide to fight a bill: You have a difficult battle ahead.

“If you owe the money, and you admit to the court that you owe the money, then the judge has no choice but to enter the judgment,” said Griffin.

Miller agreed. “It’s not a winning battle,” he said. “Very rarely do you win those.”

Has he ever won in a debt dispute with UVA?

“I haven’t. Ever.”

Trial and tribulation

“I’m not a lawyer, and I don’t pretend to be a lawyer,” Nelson said. But over the course of the last year, she tried to fill the role on her own case. She asked for a jury trial, and the argument she laid out in court was this: The agreement she’d entered into when she signed the card handed to her on June 13, 2012 was so one-sided, thanks to unequal bargaining power and a lack of facts, that it constituted an unconscionable contract and was legally void. UVA was aware of about how much her procedure would cost and could have given her an estimate, Nelson said. The hospital had a stated policy of offering financial counseling. She was given neither, she said. Instead, she was handed a small card at a vulnerable time and told to sign.

“I don’t know how one could say that that constitutes a binding contract for unknown procedures, unknown costs in perpetuity, when it provides absolutely no resource for validating the contract,” she argued in court. “There’s no website, there’s no contact person; nothing. It’s just sign here and you’re bound to us forever.”

But the witnesses she tried to call—financial aid staff who could have testified that they didn’t counsel Nelson ahead of her surgery—were successfully quashed by Hetzel, the attorney representing UVA.

In the end, it came down to that little card she signed more than two years ago. Whether or not UVA had responsibly informed Nelson or determined how she would pay was outside the scope of the case, Judge Higgins said, and when it came to whether the card counted as a contract, she agreed with Hetzel. She granted summary judgement, and the jury never deliberated.

Case Number CL13-218, The Rector and Visitors of the University of Virginia versus Elizabeth Ann Nelson, was resolved, and Nelson was on the hook for another $8,377—accrued interest, plus Hetzel’s fee.

Nelson’s legal fight isn’t over. She’s filed notice of her plan to appeal Higgins’ ruling. She just won a small victory in a hearing this week, successfully stopping the illegal garnishment of her Social Security benefits.

Part of what’s driving her is a belief that the system needs to change. “It would have been so easy for the Medical Center to have provided information about costs, alternative health coverage and payment options,” she said. “For whatever reason, they did not.”

But she also knows that the cost of failure—to win an appeal, or to work out an agreement with the hospital, which she still thinks is possible—could mean bankruptcy and the loss of her father’s farm. She doesn’t see that as an option. Nelson said she’s determined to pay what she owes, she just needs time.

“I wasn’t taught to walk away from my obligations,” she said.

*Clarification: This story previously stated that the hospital can turn away patients with non-emergency conditions. It has been changed to reflect the fact that the hospital can only refuse care to those who are seeking treatment for conditions deemed not medically necessary.