Less than two weeks before the fifth anniversary of the deadly Unite the Right rally, the City of Charlottesville announced it would not be terminating an employee who participated in the January 6, 2021, insurrection at the U.S. Capitol. After former Charlottesville police chief RaShall Brackney accused the city of refusing to discipline the employee—IT analyst Allen Groat, who works with the police department, sheriff’s office, fire department, and rescue squad—in June, city leadership provided limited information on the matter until last week’s City Council meeting.

During the August 1 meeting, interim City Manager Michael Rogers explained that the employee wrote an apology letter to him—which he refused to share publicly—and has been interviewed by the FBI three times over the past year and a half.

“I’ve spoken with the employee, who has never been charged with any criminal offense,” said Rogers, declining to publicly name the employee. “The employee in question admits he attended the events at the Capitol. He posted his presence on his social media page, he shared this information with the FBI, and he was not arrested.”

“He is very sorrowful of his activities. He’s experienced a great deal of personal loss,” Rogers added. “Considering the totality of circumstances, including that it’s been a year and half without any action, I conclude that no further action or review is warranted in this case.”

According to Rogers, the Charlottesville Police Department received information from a city official—who Brackney has told C-VILLE was former city councilor Heather Hill—regarding the employee, initially thought to be a CPD officer, on the weekend of January 16, 2021. Then-assistant police chief Jim Mooney later determined that it was an IT employee, and reported his findings to Brackney and then-city manager Chip Boyles on January 20. The following day, CPD notified the FBI in Richmond.

“@FBIRichmond interviewed Asst Chief & claimed arrest pending. Boyles & IT director were informed the employee was dangerous & to revoke his IT access/privileges,” Brackney tweeted in June. In an email on August 8, Brackney clarified that Mooney was informed by the FBI that it planned to arrest Groat possibly in late January or early February.

On January 6, 2021, 31 CPD officers were also absent from work. However, “they were mostly on regularly scheduled days off. … There is nothing that we see that raises any alarm,” said Rogers during the meeting.

When asked if she was concerned about the number of CPD officers who took off work on January 6, 2021, during her tenure, Brackney said she expressed her alarm directly to former interim city manager John Blair, Hill, and CPD’s command staff following the insurrection. She instructed the command staff to check the social media accounts of CPD officers, as well as officers from Albemarle County, UVA, and other surrounding police departments. “I cannot confirm the [31 CPD officers’] days off were regularly scheduled. However, I am not sure how one makes the leap that regularly scheduled days off equates to no cause for alarm,” she wrote.

During his investigation into the insurrectionist employee, Rogers claimed there “were no city records available” for him to review, except for Mooney’s report on his conversation with the employee. In a confidential letter Mooney sent to Blair—which Brackney posted on Twitter in June, with the employee’s name blacked out—on January 20, 2021, Mooney said he had a private meeting with the employee, who he identified as the city’s IT public safety liaison. The employee told Mooney he was an “independent journalist and photographer” and was admitted to the Capitol by police officers, along with other members of the media. “It is my opinion that this is a civil, personnel matter,” wrote Mooney.

Since assuming his position in January, Rogers has not spoken with the FBI about the case. “I tried to reach the FBI, and the agent has retired,” said Rogers during last week’s meeting. Last May, FBI agent James Dwyer was reassigned from Richmond to Dallas, but “he indicated things would continue to move forward” with Groat’s case, wrote Brackney in an email to C-VILLE on Monday.

Brackney also claims that Groat lied about why he needed to take off work on January 6, 2021. “When Mooney briefed me, he spoke with the IT Director [Sunny] Hwang to determine if Groat was working that day. Hwang stated, ‘Groat requested the day off to take his wife to the doctors,’” Brackney wrote.

In an email to C-VILLE on August 8, Mayor Lloyd Snook explained that the city’s personnel policy prevents leadership from disciplining the employee since he has not been charged with a criminal offense related to the insurrection. “Most of the government employees who have been disciplined for being involved in the events of January 6 fall into one of two categories—either they have been charged with a crime … or they are a member of a government that has a ‘Code of Conduct’ for its employees that allows the government employer to take action under certain circumstances against someone who is not actually charged with a crime. We have no such Code of Conduct, though I have suggested that we look to adopt one,” he wrote.

The city will not fire an employee “just because they become a political football,” added the mayor.

Per the city’s personnel regulations, a city employee can be terminated for a felony conviction, sexual harassment, workplace violence, illegal drug or alcohol use in the workplace, and other serious offenses. Contrary to Rogers’ claims, Groat has a criminal record—in 2020, he pleaded guilty to aggressive driving with intent to injure, a Class 1 misdemeanor, after chasing a woman and pulling a gun on her at a red light.

In June, Snook initially agreed with Mooney that the employee—who he said he could not name publicly—had not committed a crime that CPD could investigate. However, after activist Molly Conger exposed Groat’s pro-insurrection Twitter account in June, Snook saw videos that “seem to show a different picture,” he told C-VILLE. He also confirmed that Conger had positively identified Groat as the insurrectionist employee.

On his Twitter account, @r3bel1776, Groat did not hide his support of and participation in the insurrection. In November 2020, Groat called on those who “love America” to “defend the republic by any means necessary.” He also posted photos of himself with far-right conspiracy theorist Alex Jones and white supremacist group the Proud Boys at a Trump rally, later claiming in a Facebook post that he served as “impromptu” security for Jones and the Infowars team. Just days before the insurrection, Groat again shared his plans to “force Congress [to] #DoNotCertify the fraudulent election results” at the “#WildProtest” in D.C. (Groat confirmed to C-VILLE that the account belonged to him.)

In body-worn police camera footage obtained by Conger, Groat can be seen inside the Capitol recording on his phone. When police ordered the rioters to leave, Groat did not. “We love you guys. … It’s their fault not ours,” he told the police, motioning to Congress.

“It has been reported that more than 800 people who … entered the Capitol on January 6 have been arrested and charged,” Rogers said during last week’s meeting. “In this group are individuals who are pictured and filmed by themselves [engaging] in destructive acts or being disruptive. The arrests stem from their criminal activity—not merely their presence in the Capitol.”

While Groat’s Twitter account can no longer be found, he may now have an account on Truth Social, a social media platform founded by former president Donald Trump. On August 3, Truth Social user @R3bel1776—an almost identical username to the one Groat used on Twitter—asked his followers to pray for him, “as I was recently doxxed for my patriotic participation, and it is affecting me in my career and relationships,” according to a screenshot posted by Conger.

The FBI in Richmond has said it cannot reveal if it’s interviewed anyone from Charlottesville involved in the insurrection—the FBI’s Washington, D.C., office is responsible for filing charges against the rioters, reports The Daily Progress. The FBI could not be reached for comment for this story.

During public comment last week, community members pushed back against Rogers’ claims that Groat did not commit a crime, and called for the IT analyst to be immediately fired.

In an interview with C-VILLE, activist Ang Conn pointed out that Rogers has “no stakes” in the community as a temporary city leader, and accused him of not caring about the safety of Charlottesville.

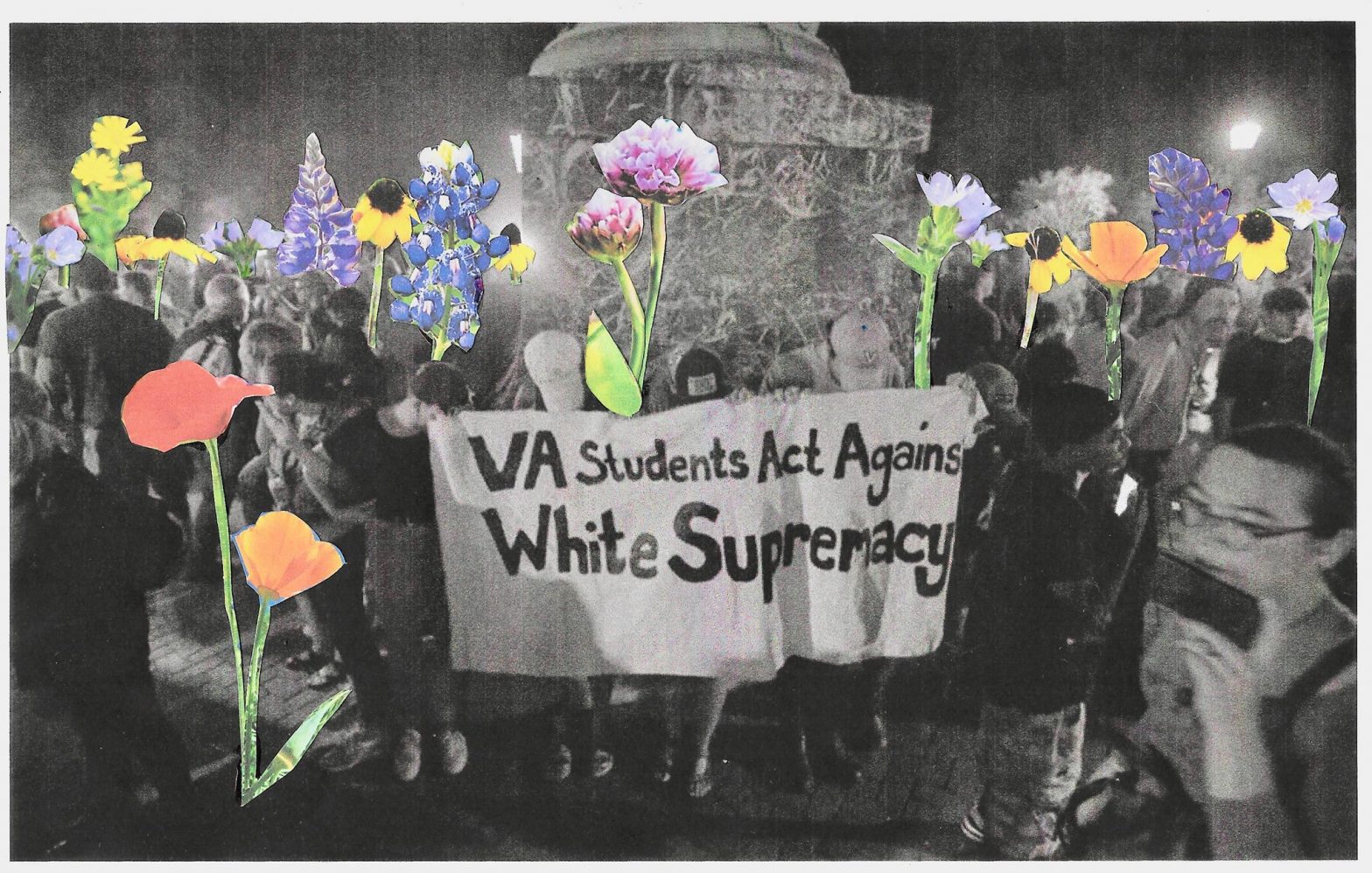

“It is a total slap in the community’s face…we have a white supremacist on our payroll and they’re going to remain there because they wrote an apology letter,” said Conn.