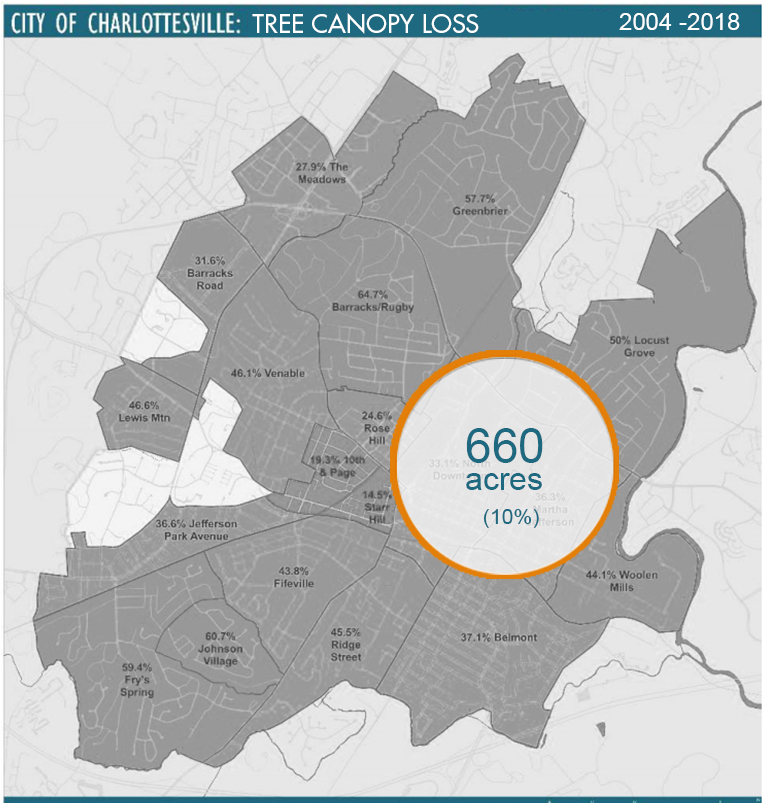

In 2004, Charlottesville’s tree canopy covered 50 percent of the city. In 2018, it covered just 40 percent of the city—meaning the city has lost one-fifth of its total tree cover. Eleven of Charlottesville’s 18 neighborhoods—including North Downtown, Woolen Mills, Belmont, Martha Jefferson, and Fifeville—now have below 40 percent canopy cover, according to the city Tree Commission’s latest annual report.

That has real effects on the people who live in town. “Low canopy neighborhood means that there’s more space that has no shade and therefore more solar radiation coming down, hitting the pavement, pavement heats up, and then you have these heat-island effects,” explains commission vice-chair Jeffrey Aten.

With very few trees nearby to absorb sunlight, low canopy-neighborhoods experience much higher temperatures, making it harder to breathe. Heat can also worsen diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, stress, and mental health issues. The effects aren’t evenly spread. Thanks to racist redlining practices, historically Black neighborhoods Starr Hill and 10th & Page have below 20 percent tree canopy—making them up to 30 degrees hotter than their higher-canopy counterparts, and bringing higher energy bills in the summer.

“We’re anticipating that if the trends that were from 2004 to 2018 continue into these next few years…we’ll continue to see that drop in canopy,” says Aten. The current canopy is estimated to be around 35 percent.

The commission’s goal is to have at least 50 percent average tree canopy across the city, with each neighborhood having at least 30 percent canopy.

Development is the main factor behind the tree loss, the commission says. As the city continues to build new housing for its growing population, more and more trees—often with large canopies—are cut down, and never replaced. Storms, like January’s massive snowstorm, can bring down tons of trees, too. Then there’s the emerald ash borer, an invasive beetle that feeds on and lays its eggs in the bark of ash trees, ultimately killing the tree. Over the past few years, Charlottesville Parks & Rec has treated 30 of the city’s important ash trees, but will need to remove about 300 over the next five years.

The Tree Commission hopes to see more investment in the canopy. Lack of funding means the city has not met its annual goal of planting 200 trees for five years in a row. Last year, it only planted 23 trees, mainly in parks and public right-of-ways. And over the past five years, it’s planted an average of 108 per year.

The city manager’s proposed FY23 budget includes $75,000 for tree planting and $105,000 for removing ash trees. The commission hopes the final budget will allocate at least $100,000 for planting.

Some community members are taking the problem into their own hands. Last year, the Tree Commission and Charlottesville Area Tree Stewards—in partnership with City of Promise—founded ReLeaf Cville to educate homeowners on the importance of tree canopy, and provide them with free trees. Since the fall, the volunteer group has planted 14 trees in 10th & Page. This month, the city’s utilities department—in partnership with the Arbor Day Foundation—is also providing 200 free trees to customers.

For future developments, the commission hopes the city will increase tree requirements, and require builders to pay fines for removing or damaging public trees. “We want the [city zoning rewrite] to be a much stronger document, and require more new trees, protection of our existing trees, and enforcement if a developer damages a tree,” says commission chair Peggy Van Yahres.

The commission also encourages the city to create a natural resources manager position in the Neighborhood Development Services department.

“They just would be able to give the Planning Commission or staff certain environmental assessments as these projects are developed,” says Van Yahres, “[so] it becomes a part of the decision making—it’s not an afterthought.”