The folks at Visible Records want to lift artists up. To do so, they’ve had to slow things down.

The newish art studio/gallery concept, backed by The Bridge/Progressive Arts Initiative and located in the former office space at 1740 Broadway St., opened last November. But the artist-run consortium, which highlights minority and low-income producers, still finds itself carefully navigating COVID-19 concerns. Organizers say they aren’t as far along in their mission as they might’ve expected at this point.

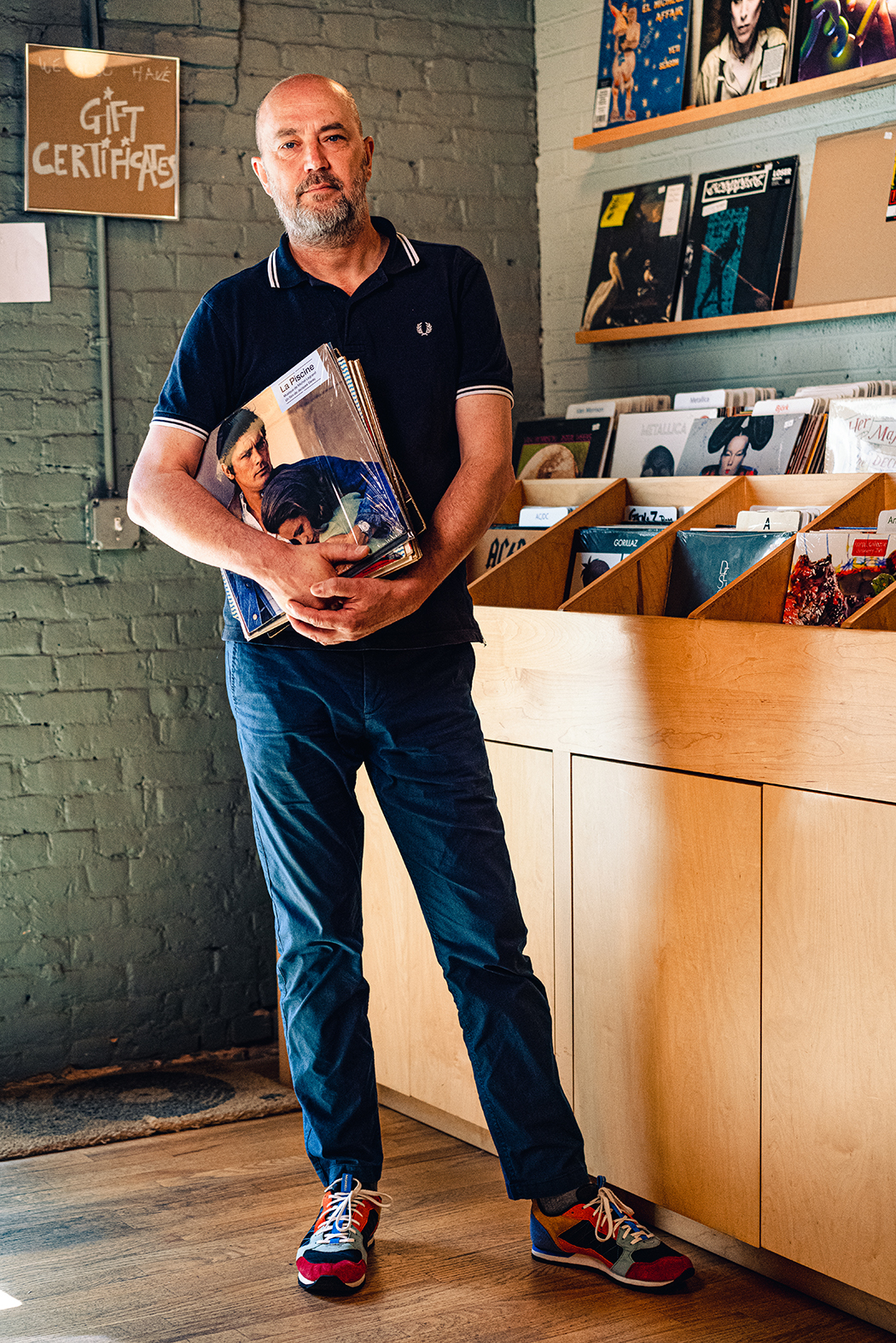

Visible Records’ studio portion—23 distinct spaces from 130 to 312 square feet in size—is less than two thirds full. And the gallery side saw its first exhibition open on August 6, nearly nine months after Visible Records’ first tenants took up studio space. “We’ve had no other option than to move really slowly,” says Kendall King, who heads studio operations.

But the slow pace has almost certainly been a blessing, King says. Building a community around the right artists takes time.

One of the firsts to use a Visible Records studio herself, King says the space has been invaluable in her own production of large-scale prints. She thinks other artists will benefit similarly—not only from the dedicated studios but also from the available common area, where they can collaborate and be inspired by others. “We give artists time and space to take stock of where their career is going.”

Getting into the studio is the first step, and Visible Records’ vetting process for new tenants is deliberate. Because the studio’s intention is to lift up marginalized artists, space is available by application only and has no set price. The community selects artists for inclusion based on fit—whether it be in terms of mission, medium, or demographic.

“We go through a process—everyone who applies that we also want to have as part of the community, we ask them what they can afford without impacting them negatively,” King says. “It might look like someone who helps doing work around the space. Or it might look like us raising money to help them.”

Fundraising has gone well, King says, largely because of Visible Records’ association with the established nonprofit Bridge/PAI. King doesn’t believe the consortium will be limited by money as it selects artists for inclusion in the near future.

King operates the studio space alongside another local artist-in-residence, Morgan Aschom, who acts as manager of the larger warehouse housing Visible Records. The multi-use space was converted after its former tenant, data management company Data Visible, closed in 2014. What remains is 55,000 square feet now encompassing Decipher Brewing, Grow Coral Reefs, Patois Cider, Metal Inc., A2D Appliance Sales, Dreadhead, The Freeman Artist Residency, recording studios, and other small businesses, in addition to Visible Records.

A separate team of local and regional arts industry insiders direct Visible Records’ gallery side, King says. The space’s first exhibit, which closed September 14, is Tiahue Tocha, featuring art by the Colectivo Rasquache. The artists have been unable to return to their home in San Francisco Coapan, a community in the volcanic region of the State of Puebla in Mexico, due to the pandemic.

“It’s just been going great—people are coming to see it,” King says. “The Rasquache collective is entirely aligned with our community. Every day when I come to [the gallery], I am moved and provoked thoughtfully by it again. There is such a range of mediums and contributions to it, but you can tell when you are in the space that these artists have the same energy and intent.”

Beyond its first exhibition, Visible Records has a full schedule lined up for the remainder of the year. Next up is the Freeman Artist Residency, running September 25 to October 30. Established by University of Virginia Professor Neal Rock, the residency program intends to lift up Black artists who are first-generation college graduates.

A solo exhibition featuring Fidencio Fifield-Perez will follow, from November 4 to December 11. Fifield-Perez lends his perspective as a native of Oaxaca, Mexico, to the debate over borders, edges, and the people passing them. Closing out the year and moving into 2022 will be a group exhibition of the current Visible Records studio tenants. The exhibit will open December 17.

With gallery operations scheduled for the foreseeable future, Visible Records can now continue the slow process of finding and vetting possible tenant artists. One remaining hurdle, King says, is that outsider artists often don’t know what’s available to them.

“We’ve subsidized, partially or fully, at least five artists here,” King says. “And we’ve always had at least a third of our artists partially or fully subsidized. I would urge people—if this is how you want to make your mark on the community—we are the place.”