Attempting to sum up a person’s life in a few words is often an unreasonable, almost futile, effort. But James Yates has a word for his wife, artist Beryl Solla, who died February 19 after a 13-year battle against cancer: Yes.

At some point during their 43-year marriage, Solla made a wooden folk-art inspired sculpture for Yates, a cutout wood angel holding a banner that says “yes.”

“It was mainly in response to my tendency to focus on what was wrong with the world, to focus on the negative,” says Yates, also an artist. “She really encouraged me to focus on what I could say ‘yes’ to in the world. I said ‘yes’ to summer, said ‘yes’ to flowers. I said ‘yes’ to spring, said ‘yes’ to a garden.”

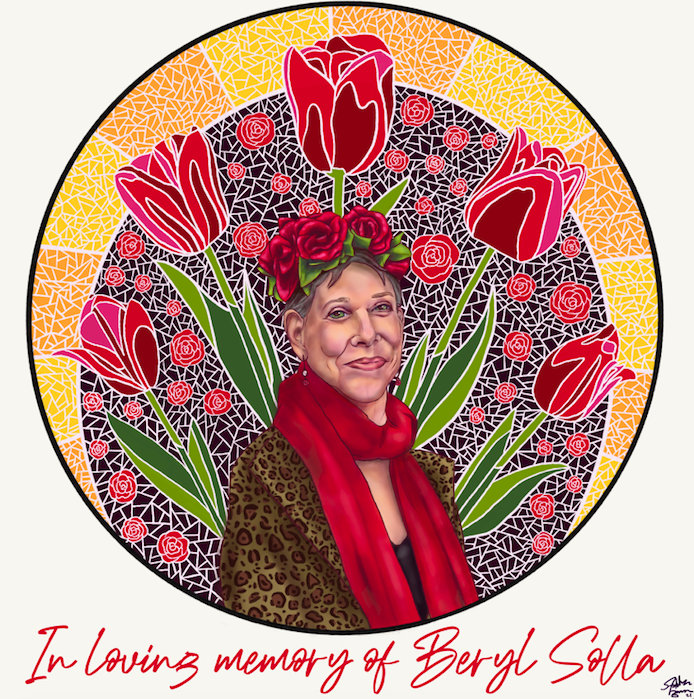

Best known for her large mosaic murals (including one at McGuffey Park), often made in collaboration with people of all ages, Solla taught at Piedmont Virginia Community College for 15 years. As chair of PVCC’s visual and performing arts department, she advocated relentlessly on behalf of students and faculty to ensure that they had what they needed—a flat space for officeless adjunct professors to grade portfolios, a cup of tea and an ottoman for a pregnant student, a “yes” to a fantastical idea—to make and teach art.

She went out of her way to believe in people, says Lou Haney, a multimedia artist who Solla brought into the teaching fold at PVCC. “She had a way of lifting you up, and you wanted to prove her right,” she says, adding that people often went beyond the boundaries of what they thought they could do, because Solla believed they could.

Solla always spoke her mind, and her honesty was sometimes intimidating, particularly during portfolio critiques, says her longtime friend, colleague, and fellow artist Fenella Belle. “She always found something nice to say about even the most unimpressive piece…unless you hadn’t worked on it. …She did not have time for people who are full of shit.” But even that came from nurturing kindness, from knowing that everyone has something to offer the world. It was “remarkable mentoring,” says Belle.

Solla believed that art was play. She made art accessible and she made art fun. She painted the walls of PVCC’s basement-level art department in bright colors and peppered the walls of other campus buildings with student artwork. For 14 years, she made heaps of banana bread and hot chocolate for visitors to the popular “Let There Be Light” winter solstice outdoor light art show that she and Yates founded. She started a free community film series at the school. She held tile art workshops throughout the state via the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. She was funny. She paired the annual PVCC student art show with a “chocolate chow-down” to get more people in the room. Her favorite band was Talking Heads. Her students and colleagues adored her, and she adored them right back. She loved her husband, their two children, and three grandchildren deeply.

Solla “was an amazing gardener,” says Yates, who plans to continue tending to her patch. But Solla planted more than flowers, says photographer Stacey Evans, another longtime friend and colleague of Solla’s, and “although she has passed, what she has planted in Charlottesville will continue to grow.” It will. Yes.