By Michael Moriarty

Dad’s words stung like a leather belt across my backside. “You know what you are?” he asked. “You’re quick, certain, and wrong!”

It was more than half a century ago, and I was less than 10, but the sting still lingers.

I grew up in the crowded middle of seven children, where it seemed all of us were competing to get a word in edgewise, so how was I the only one who nicked that raw nerve with Dad, the nerve that screamed, “Only a fool would fail to take the time to get it right”?

I tried to do better, but I still struck that nerve with enough regularity that when Dad began (“You know what you are?”), I cringed, because I knew what was coming next. Eventually—I think I was in my late teens—Dad’s harsh critique of my decision-making ability fell into disuse. Maybe I’d grown wiser, or maybe Dad had just grown tired of trying to correct me. Probably a little of both.

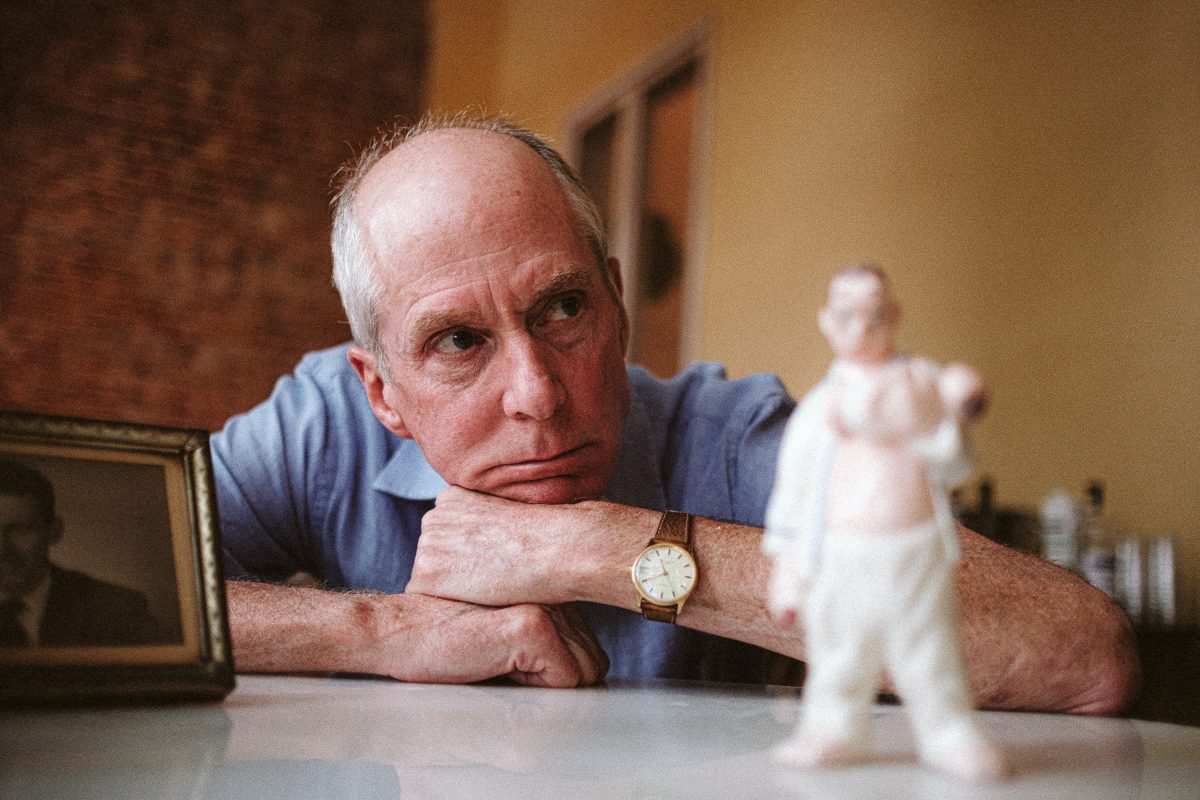

It’s been nearly 30 years since Dad died, but I’ve continued to hear “quick, certain, and wrong,” not in his voice, but in my head. Almost every time things haven’t gone as planned, I have, without forgiveness, blamed my own impatience, my own poor judgment, my own damned foolishness.

* * *

My brothers and I were clearing out my parents’ house last summer, a few weeks after our mother died, and I volunteered to clear my parents’ bedroom. Dad’s dresser had sat largely untouched since 1996, so sliding open the top drawer was like cracking open a crypt to reveal a trove of treasures buried with the deceased for his use in the afterlife.

I found the spring-top box where Dad had kept bus fare for his morning commute. I found the Swiss Army knife that was a virtual prosthetic for Dad: One minute he’d be using it to pop open a can of beer as we floated down the Shenandoah in a boat, while the next minute he’d use it to pry a hook from a trout’s mouth. I found tie clasps and cuff links that I’d seen Dad put on before Sunday Mass. I found the medals he’d earned in the service, years before he met my mom and started a family. I recognized—and left—those familiar treasures in the crypt of that top drawer.

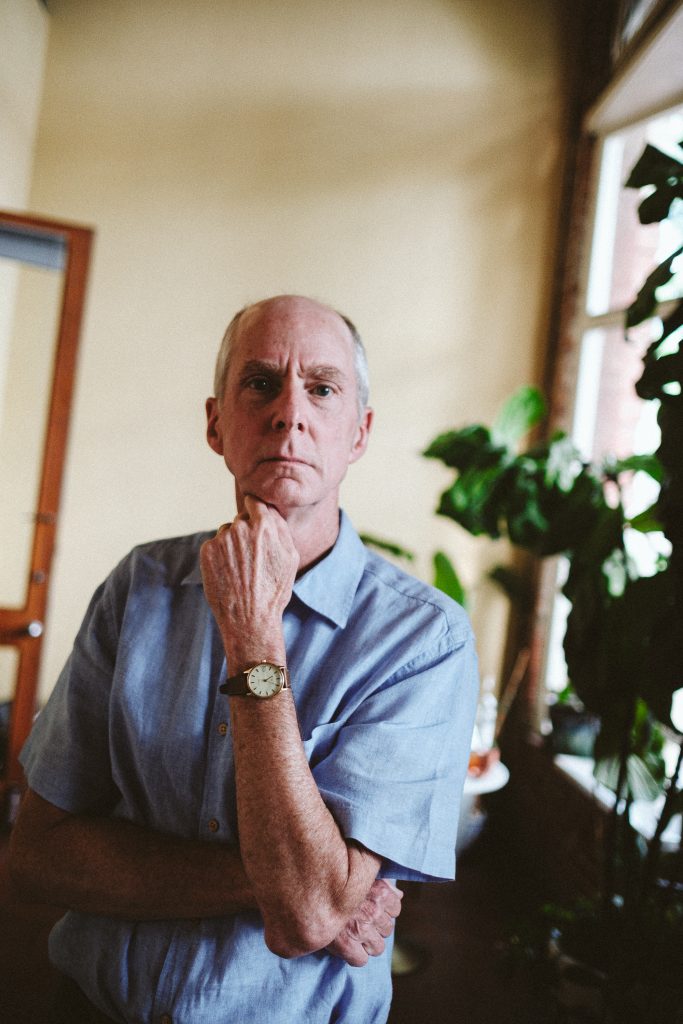

The treasure that drew my attention was one that I didn’t recognize, though I immediately knew what it was. I was 8 years old when Dad returned home from Vietnam in 1969, sporting a battery-powered Seiko wristwatch, and here in Dad’s dresser was the wind-up Timex that came before the Seiko. It hadn’t ticked in more than half a century, and despite my winding, it produced not one tock.

The wristband was indented where Dad had buckled it every morning. He’d been a barrel-chested, physically imposing man, so I was surprised to discover that the band fit my thin wrist exactly as it had his.

I took the watch to Tuel Jewelers, where the jeweler’s eyes twinkled at the challenge of bringing the old Timex back to life.

It was during the weeks that the jeweler worked to restore Dad’s wristwatch that I began to wonder if my father’s sensitivity to my quick decisions might have been grounded as much in his own experience as it was in my own actions. I thought of instances when time had been taken from him, about moments in Dad’s life when he’d been rushed to decisions he hadn’t wanted, to conclusions that ranged from unfair to cruel.

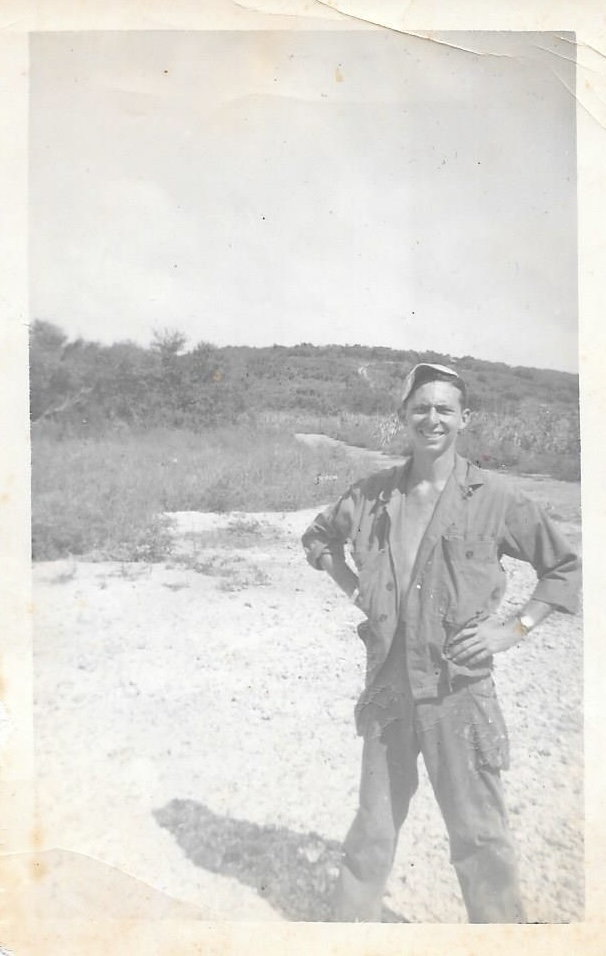

I thought first of Dad as a skinny 13-year-old, when his father—larger than life in my dad’s telling—died of a heart attack in 1938. When the Birmingham News reported the death, the story omitted Dad’s name from among the surviving family members. Maybe the reporter was in a hurry, but the slight left a scar that Dad carried for some 50 years until I uncovered the Mobile Advertiser story of the event that included his name. Still, the strongest man in Dad’s life was gone forever, reduced to an unattainable aspiration. I thought of Dad in 1943, a flight cadet in officer training, having enlisted immediately after his 18th birthday in the hopes of catching up with his older brothers, one commanding an air squadron in Burma and the other skippering a Navy ship. But, as Dad explained it to us later, leadership concluded they “hadn’t killed off as many pilots as anticipated,” so he was shipped to Saipan with the humble rank of Private, a laborer in an ammunition ordnance company responsible for loading bombs into B-29’s piloted by young men who’d earned their wings just a bit sooner. Glory, Dad found, went to other, slightly older men of his generation.

I thought about the 1950s, after Dad left the service, married, and tried to make a go of it with his own business. Dad designed and created figurines that he sold at shops and local events, until piracy of his best products (as well as a third child on the way) compelled him to exchange that dream for a steady government paycheck. As responsibilities took precedence over dreams, Dad boxed up the last of his figurines and stashed them under a bed in the nursery, where I discovered them last summer, caked in dust.

I thought about the Friday after Thanksgiving, 1964. My parents were in the dining room that Dad had only recently finished building onto the back of our house. My mom was holding in her arms my three-week-old sister when Dad spied water streaming through the kitchen light fixture. He dashed upstairs and found me, along with my diapered little brother, turning the bathroom into a water park. Dad quickly lifted me and “put” me down on the slippery floor outside the bathroom, where I slammed into the wall—and snapped my femur. I don’t remember that it hurt, only that when Dad tried to stand me up, my leg kept sliding to the side like a puppet’s.

A few days in traction, followed by a few weeks’ recuperation in that new dining room, and I was as good as new. My mom told me later that Dad had felt terrible, but I don’t remember that he ever told me he was sorry for having been, well, quick, certain, and wrong.

I thought about that years later when it occurred to me that in 1938 Dad had not only lost a father he admired, but he’d also lost the chance to slowly learn and accept that fathers sometimes make mistakes with their sons (and vice versa); that sometimes disagreement and fault do not preclude, but instead engender, respect and even admiration.

Like most people, Dad was complex, sometimes even self-contradictory, and that’s what often made pleasing him difficult. He could tell a joke with impeccable timing. He was committed to making to-do lists and getting things done—on time. He had no patience for dithering. When it came to me, my quickness in winning races at our local swim club earned his admiration, but quick answers on more sensitive matters such as race or politics earned his admonition.

As I grew older, I made plenty of mistakes—undoubtedly many of the “quick, certain, and wrong” variety. I’ve thought about one more than all the others. My sister, the one who’d been a mere three weeks old when I suffered my broken leg, had singled me out as her “hero” since we were little. Three weeks into the second semester of her junior year in college, she made a surprise visit home. Something was troubling Molly, so on the day she was to return to school, I spent the afternoon with her. Two weeks later my mother called and said “something terrible has happened to Molly,” and I realized that her hero had been quick (to dismiss the warning signs of her depression), certain (that she would grow out of whatever was bothering her), and unforgivably wrong.

It is said that the older we get, the less we know. And so it was that on that day in February 1985, I aged decades. As horrible as the loss was for my sister’s hero, though, I knew even then that it was worse for her daddy. The loss upended Dad’s world, robbed him of precious time with his only daughter, and left him (if we had this much in common) with all the time in the world to consider the unanswerable questions that a suicide bequeaths its survivors. Life, it seemed, had pushed and shoved Dad again, this time with unspeakable cruelty.

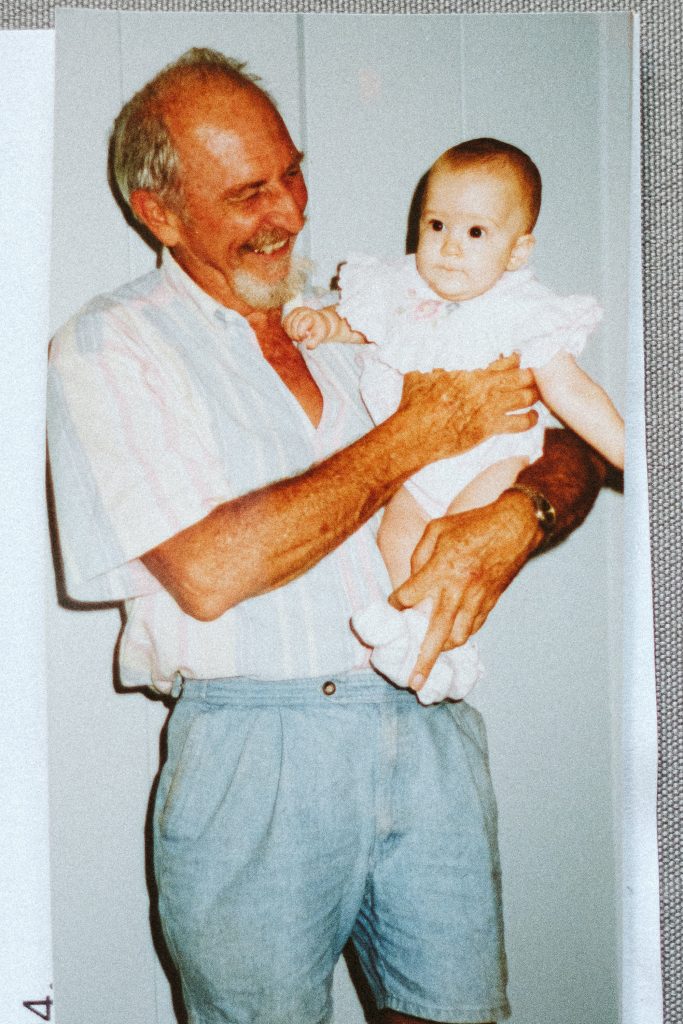

Retirement a few months after Molly’s death brought Dad relief from the “need it an hour ago” routine that characterized his 25-year career at the Pentagon, and he finally had time for the travel with my mom that the two of them had denied themselves during their child-rearing years; both relished the timeless promise brought by four grandchildren.

Photo by Eze Amos.

Life, though, would be quick, certain, and wrong with Dad one last time. A few months after his 70th birthday, Dad contracted a virus that did its damage in a furious hurry: In the space of just days, what seemed a mere cold progressed to a terrific fever and then a seizure, which left Dad in what the doctors coldly characterized as a “permanent vegetative state.” Brain dead.

Hoping for a miracle, I was, a few days later, standing next to Dad’s bed in the ICU, holding his hand, when the nearby radio began to play Rachmaninov’s Symphony No. 2, one of the most beautiful pieces of music you could ever hear—and undoubtedly one that Dad, whose own father had taken him to concerts and instilled in him a deep appreciation of classical music, had enjoyed many times. For the first time since Dad had gone under, his eyes moved (behind closed lids) and his grip on my hand tightened. I think that what was left of his brain that night still appreciated Rachmaninov, though heaven only knows if he was aware of whose hand he gripped as he listened.

About four weeks later, Dad lay in a hospital bed in that dining room that he’d built some 30 years earlier, and again I was standing next to him, stroking his limp, withered arm, when he left this world to the strains of “Solveig’s Song,” one of Edvard Grieg’s Peer Gynt suites, which I had queued up on his stereo moments earlier. I don’t know if his battered mind and departing spirit detected either the music or the touch of my hand, but I’d like to think he took with him warm memories of both.

Just before I was to pick up Dad’s watch from Tuel, one of my brothers uncovered from my parents’ things a wrinkled old photograph that I’d never seen before: It was my dad, 18 years old and rail-thin, standing hands on hips, squinting into the midday sun on Saipan, 1943. The photo is grainy, but on his left wrist is, unmistakably, the wind-up Timex.

I have a smart watch and a couple battery-powered watches that keep perfect time, but now I like to wear Dad’s old wind-up. It is beautiful, probably almost 90 years old. Sometimes it runs a little slow, other times a little fast. It is, in other words, like both fathers and sons: loved but also flawed, imperfect. Every morning when I take a minute to wind that watch, I remind myself to be a little more patient, a little less certain and, honestly, a little more forgiving. And when I place the watch on my wrist and buckle its cracked wristband, exactly as my dad used to do, I think of Solveig’s lament to Peer Gynt: “And if you wait above, we’ll meet there again, my friend.”

Michael Moriarty lives in Charlottesville and retired in 2023, following a career as a legal editor and project manager. He has been published in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, SwimSwam, and Medium.