A dedicated few have long tried to slay the gerrymander beast that allows politicians to pick their voters. For nearly 20 years, state Senator Creigh Deeds proposed redistricting reform bills that typically died in subcommittee. In 2013, attorney Leigh Middleditch founded advocacy nonprofit OneVirginia2021 to reform redistricting, an initiative that was seen as a long shot at the time.

But last year, 66 percent of voters approved a constitutional amendment to have district lines drawn by a bipartisan commission. The commission is ready to roll once the 2020 census numbers come in.

There’s the rub.

All hopes of conducting 2021 Virginia House of Delegates elections in newly drawn districts crashed when the Census Bureau announced that redistricting data will not be available until September 30, way too late for Virginia to amend districts before the November elections for state offices.

“It was very disappointing that it was at the mercy of census data,” says Middleditch.

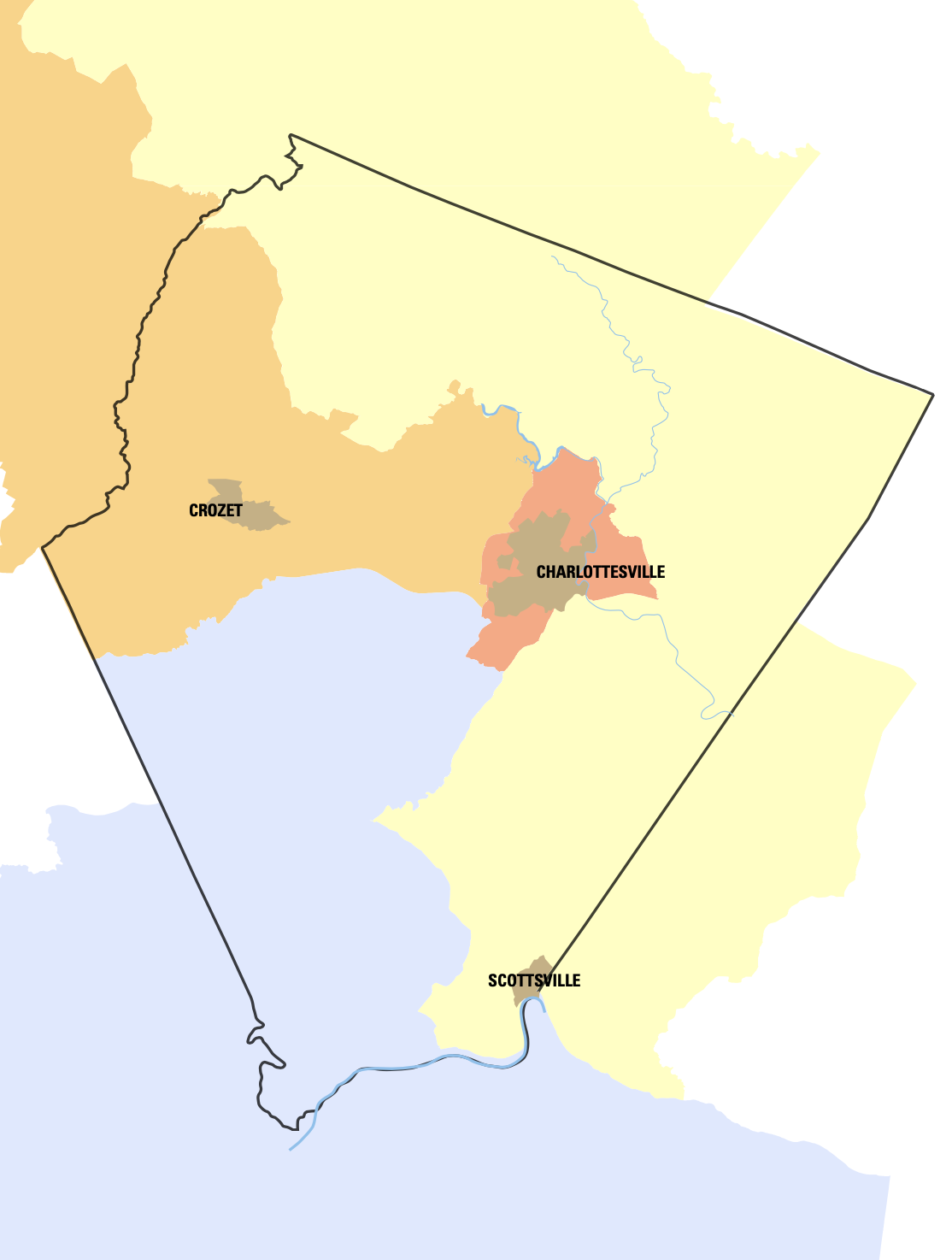

That disappointment is particularly keen in Albemarle County, which is split into four House of Delegates districts and has two state senators. Only one of the six representatives lives in Albemarle.

Sixty-six percent of Albemarle County voted for Joe Biden in 2020, but at the state level the district is represented by four Republicans and two Democrats. Only one of those districts is even remotely competitive—in 2019, five of the six Albemarle pols won their races by at least 19 percent.

“In my ideal world, Albemarle wouldn’t be four [House] districts,” says Albemarle County Democratic Party chair Stephen Davis. “It would be two,” made up of Charlottesville and Albemarle County in two compact districts and communities of interest, key criteria in fair redistricting.

Although Albemarle County has turned blue over the past decade, currently Crozet, Ivy and western Albemarle are sliced off into the 25th District, which includes parts of Augusta and Rockingham counties, represented by Republican Delegate Chris Runion.

Runion says in an email that western Albemarle shares with his Shenandoah Valley constituents the same “transitional position” of being neither high-density urban nor low-density rural, although the district has components of both. Of Crozet, he says, “Overall, I believe we are always more alike than dissimilar.”

The 59th District puts southern Albemarle into a district that stretches south of Lynchburg and is represented by Republican Rustburg resident Matt Fariss.

“Certainly an improvement would be three districts, not four,” says Davis. “The 59th District goes to Campbell County. It dilutes the Democratic effort in three [Albemarle] precincts.”

And the 59th is not a community of interest, he says. “We don’t even get the same television or radio stations as Lynchburg.”

Ben Moses is a North Garden Dem who plans to challenge Fariss in November in a district drawn to favor Republicans. “When I decided to run,” says Moses, “my presumption was I would be running on the existing lines.”

Had the lines in the 59th been redrawn, he could have faced a different—and possibly more favorable—electorate. “My excitement in running is not dampened by redistricting,” he says. “There’s so much else we can focus on.” He notes that all 45 Republican-held House of Delegates seats will be challenged by progressive candidates who call themselves the “broadband caucus,” a nod to what many rural communities lack.

Virginia’s constitution requires that lines be redrawn every 10 years based on the latest census. Because that’s not going to happen this year, state elections will use the current lines—and there’s a chance that the state will have elections three years in a row.

Davis predicts that once people know what the new districts are, there could be a court challenge that would result in an election in 2022, and then back to the regular state election schedule in 2023.

Delegate Sally Hudson, a Democrat who represents Charlottesville and part of Albemarle in the 57th District, says the delay is “one of many unfortunate consequences of COVID and the Trump administration. It’s frustrating to all of us who want fair districts.”

The issue probably matters more to people in other districts, she says. “I have one of the few coherent districts on the map.”

Liz White, executive director of OneVirginia2021, points out the delay in redistricting offers opportunities for voter education, resources, and tools, “especially for those historically marginalized by redistricting.”

When drawing new lines, the Virginia Redistricting Commission is required to try to keep “communities of interest” together in the same districts.

“It’s easier to define what a community of interest isn’t,” says White. It could include language, economic interests, or a faith community, she says. It could be, “We all go to this one hospital or we all go to this rec center.”

Communities of interest are not based on “political affiliation or relationship with a political party, elected official, or candidate for office,” according to state code. Citizens can tell the commission what their community is through public hearings or online.

Despite the census setback and the uncharted territory for state elections, she says, “So far we’ve been pleased with the makeup of the commission,” which has eight legislators and eight citizens, equally split between Democrats and Republicans.

Deeds, a Bath County Dem whose own gerrymandered Senate district includes Charlottesville, is not surprised with the latest setback. “The way the last administration handled the census, I wasn’t shocked,” he says.

He says information is already available on where population changes have occurred. “We know which areas have grown and which have lost people. We have a new game plan and we don’t know where it’s going to go.”

For North Garden resident Diana Mead, it’s been a long 10 years since the lines of the 59th District were last drawn. “My outrage over the years has settled into real disappointment with Virginia politicians,” she says. “I am just tired of feeling disenfranchised.”