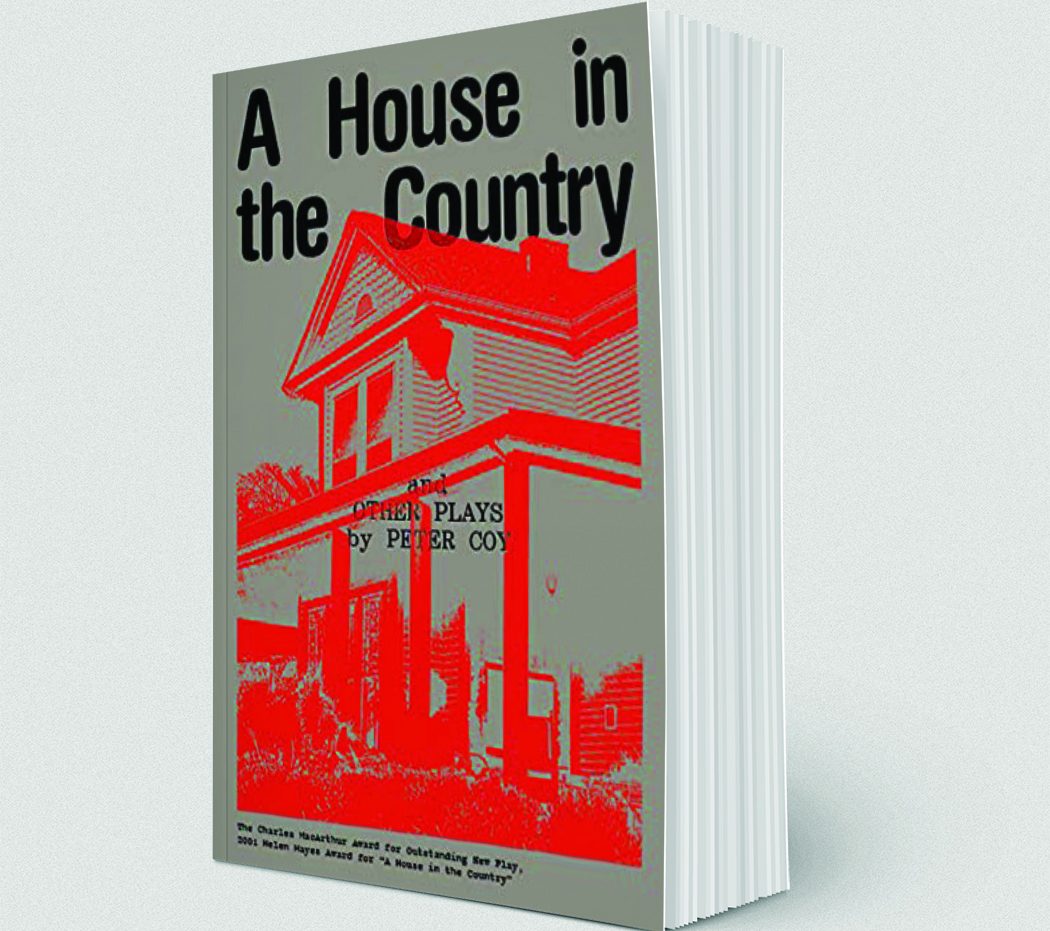

In the plays collected in his new book, Peter Coy includes a range of extreme human behavior, from fears most dreaded to murders most foul, from rank dishonor to impish perversity. He also infuses characters with love, hope, forbearance, and sometimes forgiveness. A House in the Country and Other Plays gives its audience a shot of redemption in the five works, and also gives theater-goers and readers an opportunity to thoughtfully contemplate pressing issues.

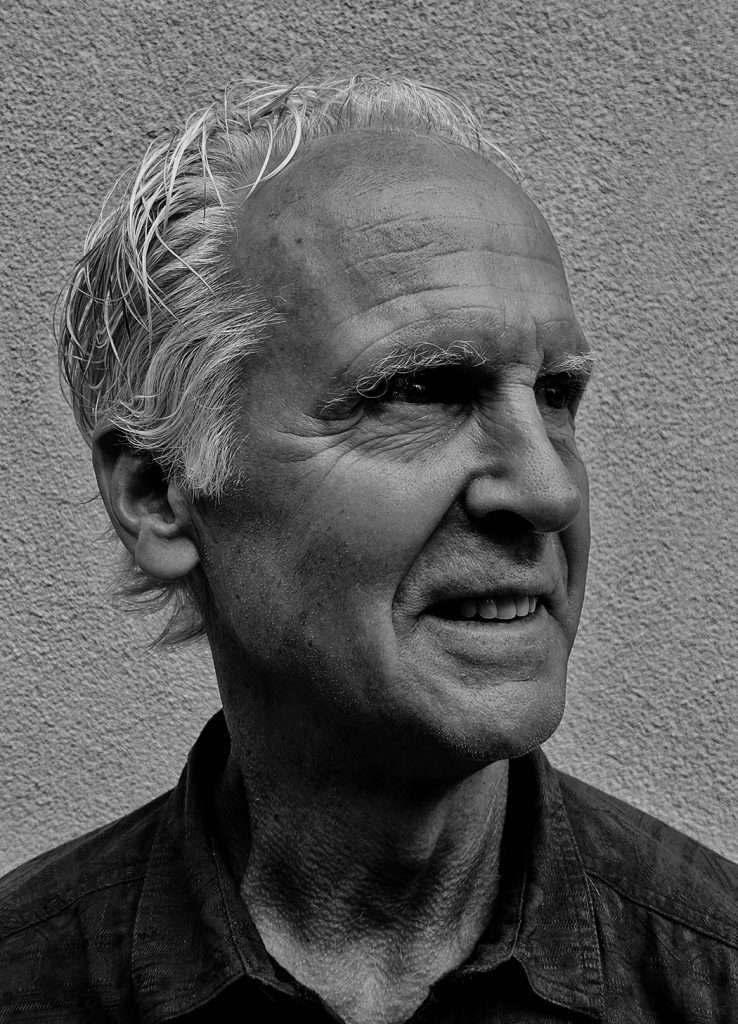

Meeting Coy, a genteel, seemingly easygoing man, it’s difficult to square his soft-spoken words with the imagined scenes he asks an audience to take on, the visceral images that materialize from dialogue, from characters’ memories and admissions.

Coy has lived in Nelson County for 30 years, but says he can’t claim it, “because your grandparents have to be born there.” An all-American lacrosse player at UVA, he also trained as a director in the drama department before departing for a life of camaraderie in the theaters of New York and Washington, D.C. He’s a founding member of several theater troupes; the Earl Hamner Theater in Afton is his most recent company. He’s also won a Helen Hayes Award for Outstanding New Play.

“From the adaptation of a classic story, to the highly imaginative use of an oversized doll, to the use of music, and inventive uses of time, Coy explores the possibilities inherent and unique to the stage,” says the Charter Theatre’s Richard Washer of Coy’s five plays, which seem to spring from a quest to understand what makes a typical person despair enough to pursue the terrible.

A House in the Country is based on a slightly toned-down version of a gruesome crime in Pennsylvania. It was inspired by a brief item in a newspaper, and it explores how Coy answered his own questions about such a traumatic event.

The believability in his plays comes from deep study, particularly around brain trauma and post-traumatic stress disorder. He researches areas of psychology and neuropsychology to learn about what might trigger certain types of behavior.

“Making characters means creating behavior that is transparent to an inner psychology,” he says. “As a director, you try to find activities that keep things interesting on stage, and can morph, change, or reveal something about the character.” Imagination allows you to see things that are not present or obvious, Coy says. He was delighted, for instance, when he handed an actor a beer bottle, and in no time, the actor began peeling the label off.

As tragic as his plays may seem, Coy carefully deploys comedy to keep things balanced.

“Physical comedy is the most difficult acting of all,” he says. “In drama, actors can change timing in their scenes and still have the same impact. In physical comedy, scenes are much tighter.” If a character falls while managing to throw a hat onto a hook, it has to happen the same way each time.

In some of his plays, he introduces the buffoon, who instead of playing the fool, ends up mocking the audience. The playwright is also versed in commedia dell’arte, an Italian form of comedy with character types that have lasted for centuries.

In the 50 plays that Coy has written, there is complicated, lyrical, and antiquated language. Sometimes he makes it even more challenging. In Poe & All That Jazz, his Edgar Allan Poe—part clown, part doomsayer—speaks aloud the rhythmic, escalating verses of “The Raven.” At the same time, the actress who portrays his mother (and also embodies all of his ill-fated loved ones) cuts in by singing Cole Porter’s “In the Still of the Night,” as she taps like the wretched raven at his door. Music is an important component in many of Coy’s plays, including one about Mozart (not in the book), and he clearly enjoys playing with lyrics, love letters, poetry, invented words, and uneasy stutterings.

In two of the plays, Shadow of Honor and Will’s Bach, male protagonists suffer and speak as they do because of post-traumatic stress and to seemingly taunt a spouse, although the latter lines are eventually shown to burst from a dark source.

Suspense is served liberally. In a re-imagined The Gift of the Magi, based on the O. Henry story, the writer casts the characters into a gritty 1907 New York. The audience is treated to two new sets of decisions that are as heart-wrenching as they are dangerous. Both the early 20th-century community tragedy and contemporary anguish in A Shadow of Honor yield cliff hangers, as do the shame and secrets of A House in the Country.

When not writing or directing, Coy helps shape plays with Nelson County High School students, assisting them in conquering Shakespeare, Molière, and others. During his 13 years at NCHS, his students have won five first places and four second places in the Virginia High School League’s annual One-Act Play Festival.

For more information about A House in the Country and Other Plays, as well as the upcoming audiobook, go to petercoyplay wright.com.