With an array of Pride flags, masks, and posters on display, dozens of families gathered in front of the Albemarle County Office Building on a hot August Thursday to show their support for the school division’s proposed policy outlining the rights of transgender and gender-expansive students. A handful of cars sporting colorful decorations honked their horns in support while circling the building. The rally was hosted by the Hate-Free Schools Coalition of Albemarle County.

Under the new policy, transgender and gender-expansive students (an all-encompassing term for people whose gender does not fit a traditional male-female binary) may use the bathroom and locker room that align with their gender identity. Teachers and staff must address all students by their preferred name and pronouns, and complete training on preventing bullying and discrimination and fostering a safe and inclusive environment. Transgender students have been allowed to participate in Virginia High School League sports since 2014.

“All students should have the right to safety and comfort in their education,” says Ollie Nacey, a ninth-grader at Western Albemarle High School, who attended the rally. “It’s an important thing to fight for because right now it’s not automatic that everybody has that—we have to make it so that it’s a given.”

The change comes after a period of debate at both the local and state levels. This year, a new state law required all Virginia school districts to adopt policies regarding the treatment of transgender and gender-expansive students before the start of the 2021-2022 school year. Many school districts, including Charlottesville, signed off on the state-mandated policies over the summer. Others, like Albemarle, chose to pursue individualized policies after hearing from constituents in the district. And a few districts, particularly in conservative areas, have pushed back against the requirement entirely.

According to The Trevor Project’s 2021 national survey, more than 50 percent of transgender and nonbinary youth have seriously considered suicide within the past year.

If a student comes out as transgender or gender-expansive at school, a teacher or staff member will work with them and their family to develop a plan regarding their transition in school. However, the school must prioritize the wellness and safety of students who may face violence or punishment, or get kicked out of their homes if their families find out about their gender identity.

“In some cases, gender-expansive students may not want their parents to know about their gender-expansive or transitioning status,” reads the policy. “These situations must be addressed on a case-by-case basis and will require schools to balance the goal of supporting the student with the requirement that parents be kept informed about their children.”

Over the past month, some parents registered their disapproval of the policy, claiming that it allows schools to hide information from parents and puts cisgender students in danger.

According to Learning for Justice, allowing transgender and gender-expansive students to use the bathroom that corresponds with their gender identity has not increased sexual assaults or violent crimes. (Single-stall, gender-neutral bathrooms are also available to ACPS students.)

Nacey reminds the school board that the fight to protect transgender and gender-expansive students is far from over.

“We have to keep on seeing what’s working and what’s still needed,” she says. “The school board must talk to trans students who are experiencing it and how it’s affected them, and keep working at it to make it the best policy possible.”

Critical critiques

Albemarle schools recently found itself on the end of conservative ire of a different kind—the fight over critical race theory, a graduate-school level legal scholarship framework that conservatives have wrongly claimed is being used to turn primary school students into cultural progressives.

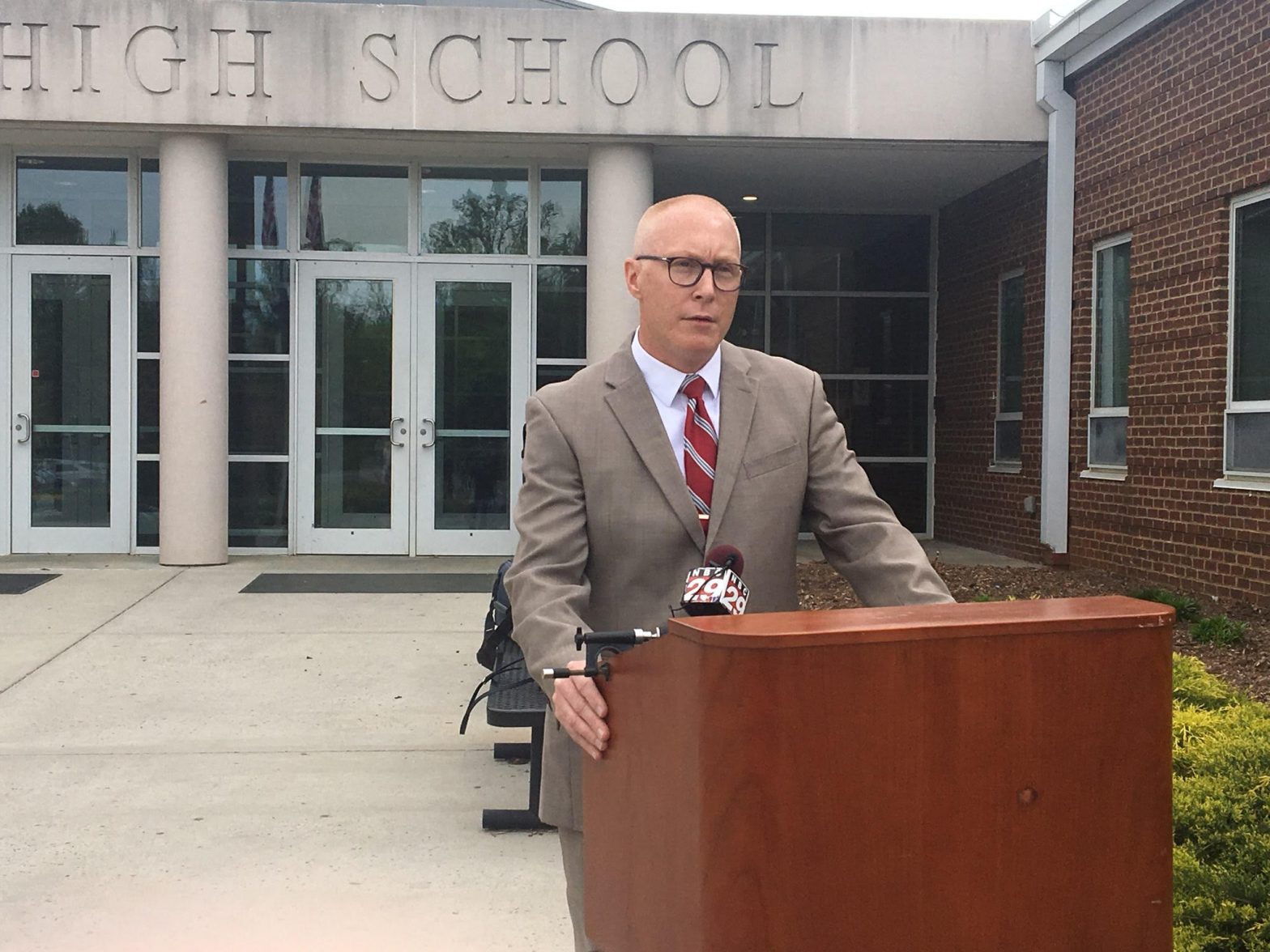

This year, a group of county parents alleged that anti-bias lessons piloted at Henley Middle School were based on critical race theory. The school board and Superintendent Dr. Matt Haas denied the claims and emphasized their commitment to the division’s anti-racism policy, which was adopted in 2019, as well as culturally responsive teaching.

Republican Philip Andrew Hamilton, who is currently running for the 57th House of Delegates District, planned to hold a rally in front of the County Office Building on August 12, calling for the school board to not implement critical race theory, but later canceled the event.

“The audacity of a political candidate to use [the Unite the Right rally anniversary] as the backdrop to his anti-CRT rhetoric is unconscionable,” says Amanda Moxham of Hate-Free Schools. “Anti-CRT movement is rooted in anti-Blackness and transphobia while being used to build up white nationalists.”

Moxham hopes that as the school year gets underway, ACPS will develop accountability and transparency strategies for anti-racism and anti-discrimination work in schools. She also calls on the district to recruit and retain more teachers of color.

“While policy is important, no policy can make a difference if the real work is not started, sustained, and nurtured as part of a healthy school culture,” she says.