By Geremia Di Maro

With the one-year anniversary of COVID-related shutdowns just a few weeks away, many people in the area and around the country have a pressing question on their minds: When will we be vaccinated?

Though distribution in the commonwealth began slowly, Virginia now ranks seventh out of 50 states in percent of citizens who have received at least one dose of the vaccine, according to The New York Times.

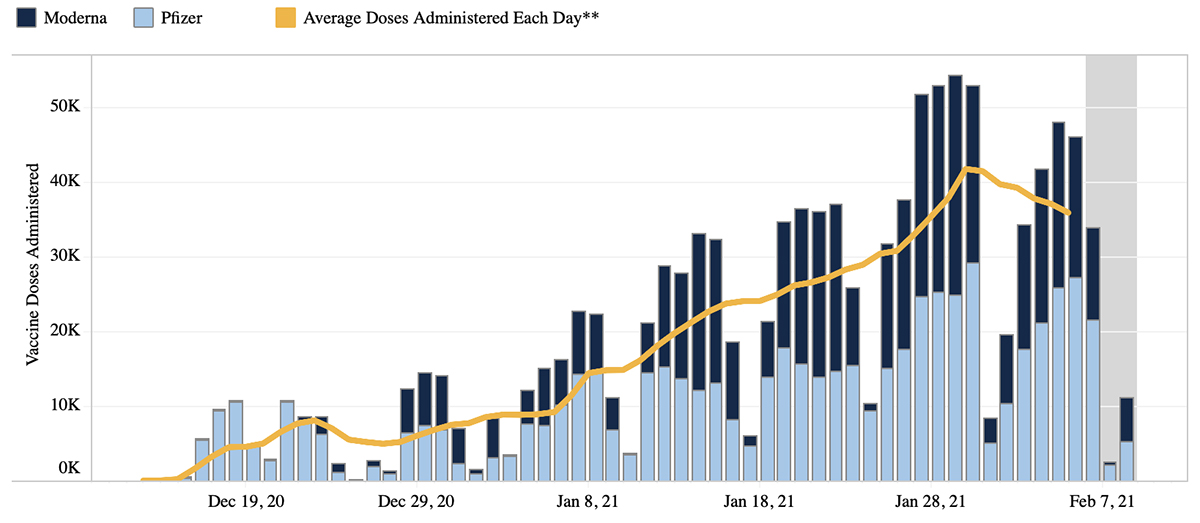

As of Monday, nearly 900,000 Virginians—or about 10 percent of the commonwealth’s total population—have received at least one dose of either the Moderna or Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine, with an average of 35,811 vaccines administered per day in the state during the past week. About 200,000 of those Virginia residents have also received the necessary second dose of the vaccine to be considered fully vaccinated.

Closer to home in the Blue Ridge Health District, which includes Charlottesville and Albemarle, Nelson, Greene, Louisa, and Fluvanna counties, per capita vaccination rates rank among the highest in the state—especially in Charlottesville, where roughly 30 percent of the city’s 50,000 residents have received at least one dose of the vaccine, according to data from the Virginia Department of Health.

Across the district, nearly 70,000 total vaccine doses have been received by local health departments, hospitals, and other care providers since the rollout began. About 50,000 of those doses have been administered, although mostly as first doses thus far. In Charlottesville, almost 4,000 individuals have been fully vaccinated with two doses out of roughly 11,000 across the health district.

Ryan McKay, director of policy and planning and COVID-19 incident commander for the district, says that the health district has led the state thanks to logistical success in the distribution process. In an area with so many health workers, it can quickly recruit vaccinators and form partnerships with local governments and hospitals, such as UVA Health and Sentara Martha Jefferson.

At one vaccination event held at the Martin Luther King Jr. Performing Arts Center last week, McKay says more than 700 individuals were vaccinated, including many local teachers as well as Charlottesville and Albemarle County staff members.

But McKay also notes that the average number of vaccines allotted to the district by the VDH—approximately 2,850 on a weekly basis at the moment—is constraining faster progress in getting shots into arms. The district’s weekly dose allocation is based solely on population.

“What’s really limiting us right now is the allotment that we get from VDH,” says McKay. “We had a big push last week to clear the inventory that was on hand, but that just makes it a little more difficult to provide greater access this week.”

The Blue Ridge Health District is currently overseeing vaccinations for individuals in Phase 1A, which includes frontline health care workers, and limited groups of individuals in Phase 1B, such as law enforcement, fire and other emergency personnel, corrections and homeless shelter employees, as well as teachers and other educators. Individuals 65 years of age and older are also currently eligible to receive the vaccine, and most of that population will be vaccinated by UVA Health.

McKay says Phase 1A has been mostly completed, adding that significant progress has been made in recent weeks on the first portions of Phase 1B as well. However, the expectation is that most individuals between the ages of 16 and 64 with underlying health conditions—who are included in Phase 1B—may have to wait several more weeks until they are able to receive the vaccine due to limited supply.

All individuals in Phase 1B are still able to indicate their interest in receiving a vaccine by filling out the district’s online survey or calling their hotline at 972-6261.

“I think the struggle we’re facing too is that once everything opened up for Phase 1B, that means half of Virginians are now eligible to get vaccinated,” says McKay. “And with only 2,850 doses coming into the health district any given week, that makes it really challenging to try to get people through from all the different categories.”

Eric Swensen, public information officer for the UVA Health System, says UVA Health has been recently administering more than 1,000 vaccine doses per day.

“Vaccine supplies are expected to be limited during the next few weeks, and we are adjusting our capacity to reflect that change,” says Swensen.

Since the vaccine rollout is overseen by the VDH and individual health districts, says Swensen, it is currently unclear whether or not will take the lead on administering vaccines to university employees, faculty, and staff who don’t work in health care.

Moving forward, McKay says the health district plans to hire contracted employees to carry out vaccinations, train paramedics and EMTs to administer vaccines, revamp the district’s online appointment system to better schedule second doses, and ensure that the vaccine rollout is equitable by guaranteeing access to communities of color.

“We know across the country, in Virginia, and in our own health district, communities of color have had a disproportionate amount of hospitalization, deaths, and cases,” says McKay. “So we want to make sure that we’re providing equitable access [to the vaccine].”

To determine if you are eligible to be vaccinated in the near future and see a list of upcoming vaccination events, visit the Blue Ridge Health District’s COVID-19 page on the VDH website.