The Freedmen’s Bureau, founded after the Civil War, was a government agency with the goal of providing goods and services to newly freed African Americans, helping them become self-sufficient following emancipation. An 1867 request to the bureau for food describes a household of five: one 48-year-old, two 80-year-olds, and two 100-year-olds, one of whom was named Betsy.

When she saw this record, Dr. Shelley Viola Murphy, descendant project researcher at UVA, had several thoughts run through her head. Betsy was born before the country became the United States of America. She had likely been enslaved her whole life. And after emancipation, there she was, 100 years old, seeking food assistance.

Stories like Betsy’s drive Murphy’s passion for genealogical research, which involves tracing a person’s ancestral descent in order to learn more about their family.

“If I was a descendant [of Betsy’s], if I had the time, I would try to research her, to call out her name, because you know what? She lived through the torment, the violence, the servitude, the whole nine yards, and it’s more to be proud that she survived it,” says Murphy. “It’s about the stories. And no matter what, families gotta tell these stories, and they gotta call out their names, so they’re really not forgotten.”

Murphy is just one of several genealogists in the central Virginia area working to unearth local family histories. Beyond satisfying curiosities, genealogy has other benefits. Research suggests that children who have a greater understanding of their family history tend to have higher self-esteem, are more resilient, and have a greater sense of control over their lives, reports The New York Times.

Brendan Wolfe, a former editor at Virginia Humanities’ Encyclopedia Virginia, started his own genealogy research service in 2021. After realizing that some of his potential clients faced financial barriers to accessing his services, Wolfe introduced a cost-free arm of his enterprise. Every two months, he will select one applicant to receive 20 hours of research and writing, valued at $1,000. The clients will receive a detailed report that includes family relationships, historical context, sources, and images.

“When your service is connecting people to their own history, I feel like that’s really important,” Wolfe says. “Thinking more broadly, I feel as if in Charlottesville, of all places in central Virginia, we really understand what’s at stake with our history.”

Wolfe says he received over 100 applications within the first three days of the announcement, and that he hopes to recruit other genealogists to help out or find additional funding to support the initiative.

Genealogy depends on the existence of historical records, which means that events like wars and fires impact whether any records can even be found. Many records were lost, especially during the Civil War, leading to some difficulties finding records from that time period in Virginia. Otherwise, central Virginia is a good location for genealogy research.

“This place is just steeped in history, and full of people who are interested in history,” says Wolfe. “And so I think it makes it easier in some ways to do genealogy.”

Murphy specifically conducts research to try and find the descendants of enslaved laborers who built UVA, a process that involves going back in time but also tracing the line of descent forward. Her mantra for genealogy is understanding “time, place, and asking a bunch of questions.”

Murphy works from a list of over 2,000 enslaved laborers who were identified by examining the university’s financial records. The Freedmen’s Bureau is one of Murphy’s go-to collections for records of former slaves whose names were not on the census until 1870. These surviving records are often incomplete, though—some contain only first names, or common last names, making it difficult to discern who’s related to whom.

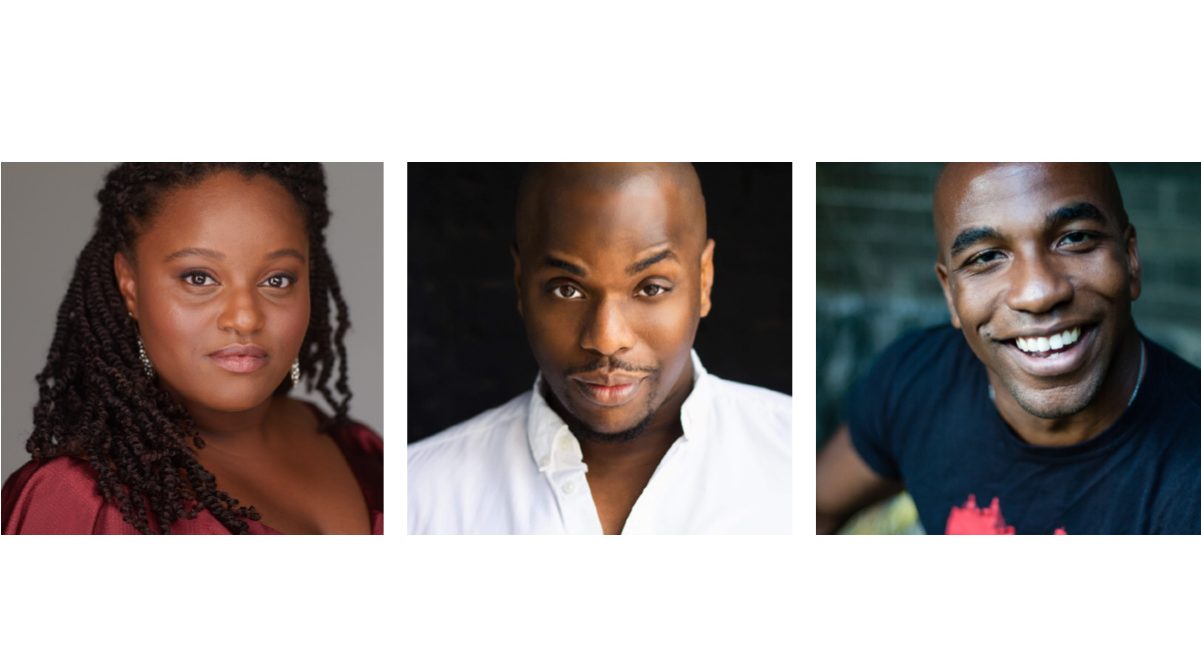

On Friday, Murphy and other local genealogists spoke at a genealogy panel hosted by the UVA Black Faculty & Staff Employee Resource Group.

Gayle Jessup White, public relations & community engagement officer at Monticello, learned that she was descended from Thomas Jefferson after eavesdropping on a conversation between her older sister and her dad when she was 13. It took her 45 years to track down the full picture—she is a descendant of Jefferson on his father’s side and was the great-great-great-granddaughter of Sally Hemings’ brother, Peter.

White chronicles her genealogical work in her book, Reclamation: Sally Hemings, Thomas Jefferson, and a Descendant’s Search for Her Family’s Lasting Legacy. The process was really about “waking up to our historical truths” and understanding how history brought her to where her and her family are today, she said.

Sly Mata, director of diversity education at UVA, spoke about how after his mother and grandmother passed, he lost access to their records—legal documents, but also things like family recipes. Although he can try to recreate them, they’ll never be the same because the records no longer exist.

“We want to be able to capture and tell those stories, and have that pride of knowing we have that knowledge. Because right now we don’t, and we’re afraid of generational curses…because we don’t know our family,” said Mata.

Thinking about Betsy and all the other stories waiting to be unearthed keeps Murphy up at night.

If she found Betsy’s family, Murphy says she’d say: “‘Did you know? Do you know about her?’ I would love to be able to hand that legacy of hers [to them].”