Shortly after the pandemic hit, Mable Christian’s daughter’s work hours were drastically cut. Christian, who has lived with her daughter at Mallside Forest Apartments—a low-income housing complex in Albemarle County—since 2015, has been unable to work for years due to workplace injury, and currently lives on Social Security benefits. The mother and daughter eventually fell behind on their rent, and applied to the Virginia Rent Relief Program in February 2022.

“We provided everything—pay stubs, employment history, the first rent of the first lease…[But] everything just kept saying ‘pending,’” explains Christian. “We kept calling the [VRRP] to see what we needed, so we made sure that we did everything they required of us, [but] they said the rest was on the landlord.”

Mallside Forest, which is managed by Security Properties, never completed the landlord’s part of the rent relief application, Christian claims. The VRRP contacted the complex’s management multiple times, “but they just didn’t follow through,” she says. Still, Christian had hopes that their application would be processed soon, and they would receive enough money to pay off their past-due rent—until they woke up to a five-day pay-or-quit notice on their door on July 19.

“We thought we were fine,” says Christian. “I thought everything would be going through.”

Christian’s situation is not unique—nearly half of Mallside Forest’s 160 units possibly received pay-or-quit notices on July 19, according to Legal Aid Justice Center. Residents—who must earn 60 percent or less of the area median income to live at the complex—have told LAJC lawyers that they applied for rent relief, but Mallside Forest refused to fill out its part of the application, preventing them from receiving any financial assistance.

A Mallside Forest leasing office employee declined to comment for this story.

After lawyers from Legal Aid Justice Center visited Mallside Forest to inform tenants of their legal rights last month, Christian reached out to the nonprofit to take on her case. LAJC believes the complex refused to comply with the VRRP process because it was waiting until Virginia’s eviction protections expired on July 1 to proceed with evicting Christian and her daughter, along with other residents who were behind on rent.

Until June 30, landlords were required under state law to give tenants a written 14-day notice to pay what they owe before proceeding with an eviction, and were prohibited from evicting those who applied to the VRRP, unless they were not approved to receive relief within 45 days. Landlords who owned at least four units also had to offer a payment plan for past-due rent. But as of July 1, landlords only have to give tenants a five-day pay-or-quit notice before filing an unlawful detainer, and do not need to offer a repayment plan or wait for rent relief to arrive.

“We just didn’t know why they were just putting us on hold, and we were waiting, and everything was pending,” says Christian. “And now I know why—they were waiting for July to come.”

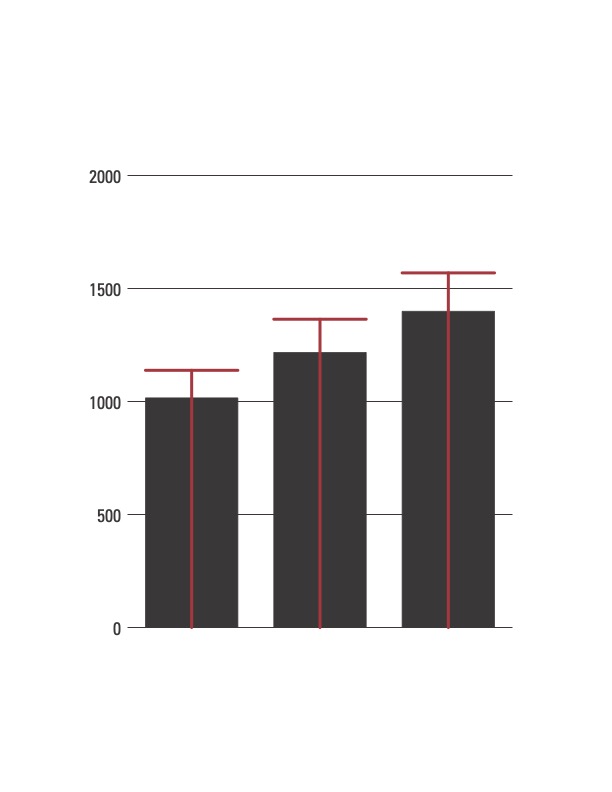

As local residents continue to struggle to find affordable housing, Mallside Forest could become one less option—the apartment complex is for sale. In a confidential offering memorandum provided to C-VILLE by LAJC, seller CBRE, a commercial real estate services and investment firm, touts the “opportunity for conversion to market [rate] upon expiration of [Low-Income Housing Tax Credit] restrictions in 2028” as an investment highlight. Without these restrictions, rent for a one-bedroom apartment could go from the current price of $1,016 to $1,783 per month in 2028, while a two bedroom could go from $1,217 to $2,152 per month. Most, if not all, Mallside residents would be unable to afford such a large rent spike, and be forced to leave their homes—nearly 60 percent of the units are occupied by residents using Section 8 vouchers, according to the memorandum.

CBRE did not respond to C-VILLE’s requests for comment.

Christian is currently working with LAJC to receive VRRP funding, and fight her eviction. For months, she and her daughter have been charged “excessive” late fees at Mallside Forest, trapping them in a cycle of debt, she claims. And every year since they’ve moved in, she says their rent has increased by more than $100, a hefty burden for people who live on a fixed income.

“It just seems like the only thing that I’m paying for is the fees, and it’s just putting me more and more in default as far as rent,” says Christian.

From 2012 to 2016, Mallside Forest filed around 120 unlawful detainers against its residents in Albemarle General District Court, according to online records. While a judge ruled in favor of Mallside Forest in about half of these cases, the other half were either dismissed, or resulted in a non-suit, which means the complex dismissed or withdrew the case.

As of August 2, the apartment complex has not filed an unlawful detainer since 2016. However, it has filed four garnishment cases against residents since 2015, including one in June 2022.

Since last week, LAJC has knocked on doors at Mallside Forest, and taken on several more clients. It has also “received optimistic-sounding news from the property manager’s office to the effect that they are (now, at least) actively working with gov2go to get people’s balances paid. From the court website, it does not appear that anyone who received a notice on 7/19 is being sued as of yet … but we are prepared to defend these evictions in court if need be,” said LAJC attorney Carrie Klosko in an email to C-VILLE on Friday.

LAJC encourages all tenants facing eviction at Mallside Forest—or any other property in the Charlottesville area—to contact them, and know their rights. Despite the five-day deadline for a pay-or-quit notice, tenants do not have to leave their home until the entire eviction process is completed, which could take two to three months, or even longer.

“The five-day notice kind of scares a lot of people. A lot of people see it and say, ‘Oh my god, I have to leave after five days,’ [and] do what we call ‘self-evicting,’” says Klosko. “But really it’s just a legal formality that the landlord has to send before they can file an eviction case in court.”

After a landlord files an unlawful detainer, a judge must hear the case and award the landlord possession of the property in order to evict a tenant. The tenant then has 10 days to appeal the judge’s decision before the sheriff serves a writ of eviction.