Twenty-three years ago this week, Albemarle Supervisors officially adopted a policy called the Neighborhood Model to encourage construction of a more urban fabric in the county’s designated growth areas.

“We were proud of the tremendous efforts put into developing the Neighborhood Model by a committee of local residents and staff,” says Sally Thomas, who represented the Samuel Miller District at the time. “It was ‘smart growth’ before that was a common moniker.”

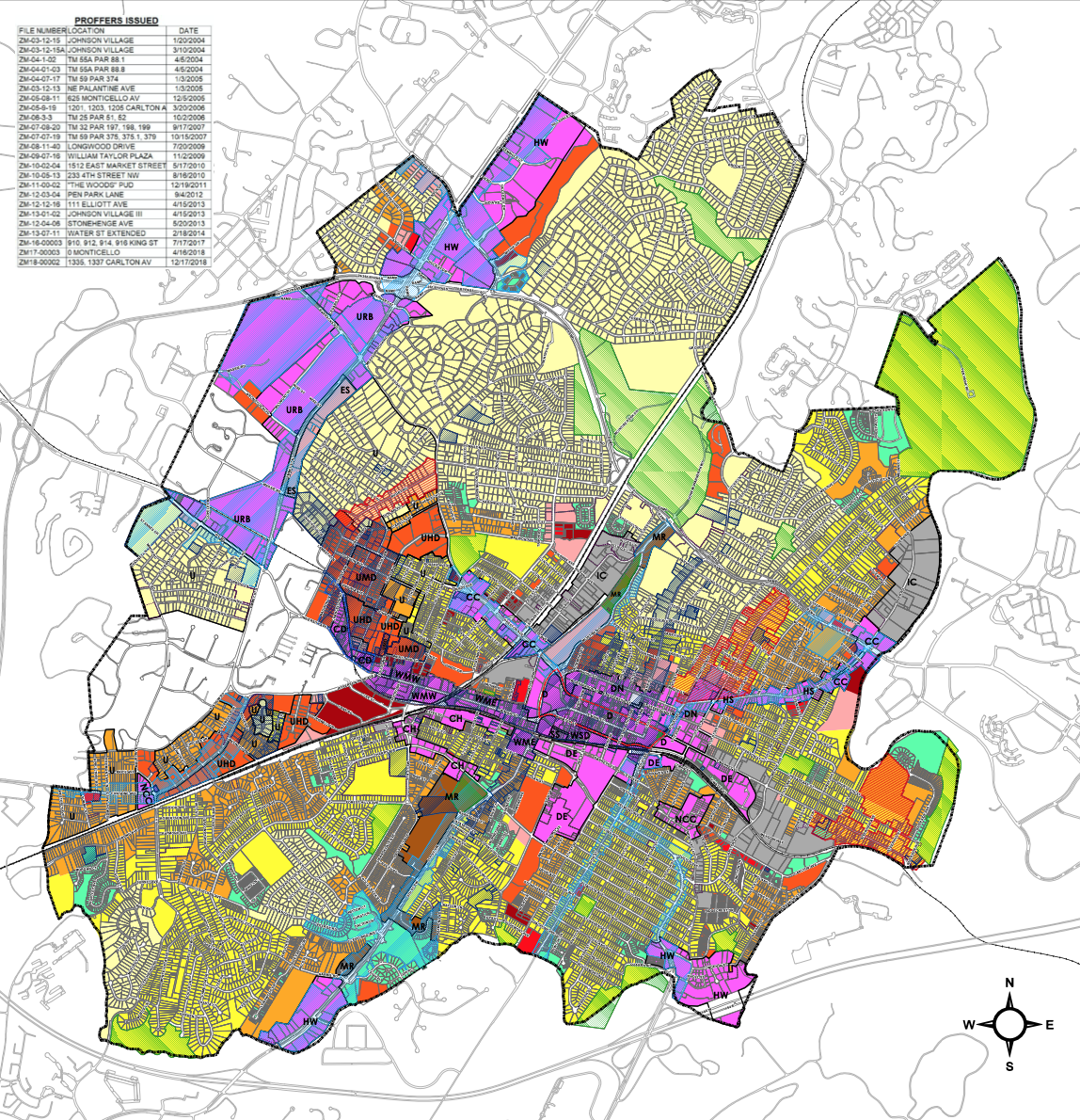

Since that time, developers have gotten approval from the Board of Supervisors by demonstrating how their projects satisfy twelve principles intended to avoid suburban sprawl by using land more efficiently. Albemarle also created master plans for each area to signal to property owners what the local government would like to see happen.

Dr. Jay Knight operates his dental practice on a one-acre parcel on Woodbrook Drive near the intersection with Berkmar Drive in a building constructed in 1996.

“Our building pretty much needs to be updated at this point,” Knight says. “I have been thinking for some time about redesigning the office and the building and thought it would be a great idea to also be able to have some residential components with the property.”

According to the plans drawn up by the firm Line and Grade, the one-story building would be demolished to make way for a four-story structure with a footprint of 6,698 square feet.

“Currently the plan is for ground-level dental office space with three stories residential above, at up to 15 units,” reads the narrative for the application written by Line and Grade.

Knight is a native of the area who says he appreciates Albemarle’s work to limit development into the rural area to attain what he described as a “great harmony.” This property is designated in the Places29 Master Plan as “urban density residential.”

However, comprehensive plans are advisory and landowners must comply with zoning. The current classification for this property is commercial (C-1) so a special use permit is required for residential use. Two special exceptions to building placement rules are also requested to allow the site to be reused.

The property is adjacent to Agnor-Hurt Elementary School, and plans show an easement for a future pathway to the school should the county decide to build one. Knight said that came at the suggestion of planners in Albemarle’s Community Development during a preliminary meeting before the application was filed.

Albemarle has amended its Comprehensive Plan several times since 2001, including the addition of the Housing Albemarle plan. This plan has a clear goal for developers: More places to live are required for the county to support anticipated population growth. The Places29 Master Plan, adopted in 2007, called for an extension of Berkmar Drive north, and VDOT has plans to connect that roadway to Airport Road where it joins the UVA Discovery Park.

Another principle in the neighborhood model is to provide residential density in places where there are sidewalks, bicycle infrastructure, and public transit. People who live in the space would have access to at least one Charlottesville Area Transit route. Knight said residents could walk to the Rio Hill Shopping Center for groceries and could easily make their way to jobs.

“I think a concept like what we’re talking about would really fit in,” Knight says.

The permit and the special exceptions will need to go through the Planning Commission and the Board of Supervisors. Knight hopes to be able to move to construction between two and five years.