Before ditching Charlottesville for California last month, former Police Civilian Oversight Board executive director Hansel Aguilar evaluated the board’s long-awaited first case, which concerned the violent arrest of a man experiencing homelessness on the Downtown Mall in 2020. Though the board was initially scheduled to hold a hearing on the case in July, complainant Jeff Fogel, a local attorney, and the Charlottesville Police Department agreed to an alternative dispute resolution on the day of the hearing, due to Fogel’s claim that two board members were biased against him. After city attorney Lisa Robertson expressed legal concerns over the ADR, the board and two parties then decided in August to allow Aguilar to conduct a neutral evaluation of the case.

On September 28, Aguilar—who resigned from the board on October 12, after accepting a new gig as the director of police accountability for the City of Berkeley, California—issued his 63-page evaluation, which determined the CPD did not “thoroughly, completely, and accurately” investigate Fogel’s complaint. On October 24, the CPD refuted some of Aguilar’s findings and rejected most of his recommendations for the department, but neglected to address multiple questions and concerns raised by the former director.

Fogel filed his complaint against the CPD in July 2020, after a Charlottesville police officer—identified as Officer Houchens in Aguilar’s report—arrested 36-year-old Christopher Gonzalez, who was lying down on the Downtown Mall. Gonzalez admitted to drinking alcohol, and said he was homeless. Houchens threatened to arrest him for public intoxication unless he left the mall, which Gonzalez refused to do. Houchens tried to handcuff him, but Gonzalez pulled away. Houchens then pinned Gonzalez to the ground, and put him in a headlock for nearly a minute, according to a now-deleted Instagram video. Gonzalez was later charged with assault of a police officer, public intoxication, and obstruction of justice, and was held without bail for almost three weeks at the local jail. Though Gonzalez’s charges were later dismissed, in September 2020 the CPD exonerated Fogel’s allegations of excessive force, and concluded that the allegations of bias-based policing were unfounded.

In his report, Aguilar asserted that the CPD should have evaluated the appropriateness of Houchens’ threat to arrest Gonzalez “through the lens” of its public intoxication policy—which directs officers to arrest intoxicated people when they “may cause harm” to themselves or others—instead of just its biased-based policing policy. Investigators also should have better questioned Houchens to determine if his actions were biased, Aguilar said.

“I like to give them the opportunity to go sober up or go somewhere,” Houchens said during an interview with a CPD investigator. “I know that these people don’t have anywhere to go, really anywhere to be. … Once we start getting calls from citizens about it, that’s kind of when it starts to become a problem, but I still will try to get them at least out of the public’s view.”

“Who are ‘these people’ that the officer is referring to?” asked Aguilar in his evaluation. “Was C.G. ‘causing a problem’ other than community members calling in about him? Under what departmental guidance, practice, or procedure is Officer L.H. operating under when he states the need to ‘try to get them at least out of the public’s view’? Is Officer L.H. suggesting that being intoxicated in public is acceptable just if it is not on the downtown mall?”

“Without asking sufficient questions … it is difficult to ascertain whether the threat to arrest C.G. followed the Department’s policy,” continued Aguilar. However, the former director agreed with the CPD that “the officer had established probable cause to affect the arrest of C.G. in violation of the state’s public intoxication law,” which states that “if any person is intoxicated in public … he is guilty of a Class 4 misdemeanor.”

In response, the CPD claimed that Aguilar was not authorized to publicly release these details from Houchens’ interview, according to a standard operating procedure—but did not explain how Houchens determined Gonzalez was a danger to himself or others, or clarify which department policy directed him to get Gonzalez “out of the public’s view.”

Aguilar also questioned why the CPD did not submit the complaint to the commonwealth’s attorney during its criminal investigation into the matter. “It was unclear what specific investigative steps the CPD Captain took (beyond the interview of Officer L.H.) to reach the conclusion that no criminal violation took place since there is only one email from the CPD Captain,” wrote Aguilar. In the email, the unnamed captain explained that the department did not contact the commonwealth’s attorney because Houchens’ use of force was appropriate and lawful under CPD and state criminal justice department policies.

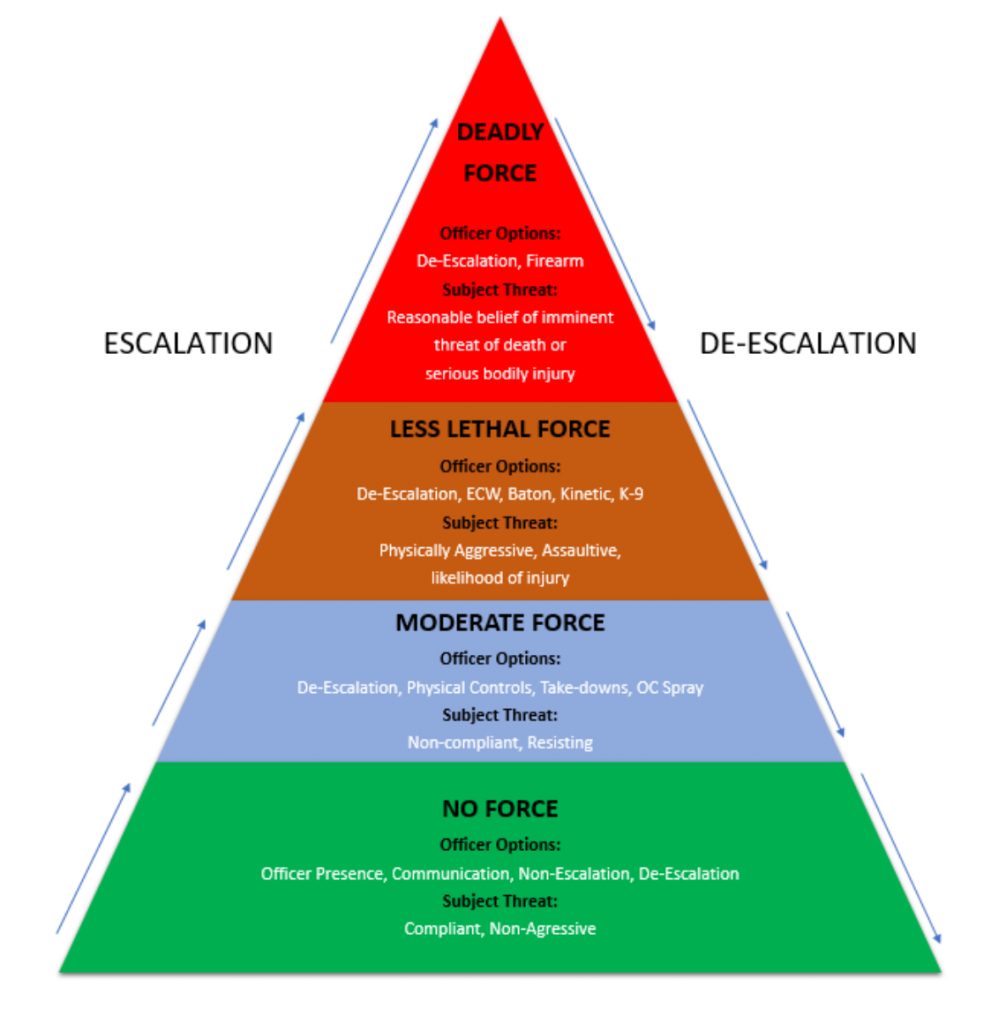

The CPD countered that then-chief RaShall Brackney agreed with the captain and criminal investigations division that Houchens’ “response to the resistance did not rise to a criminal violation” and “was in accordance” with its response to resistance policy, and therefore “did not require review by the Commonwealth’s Attorney’s office.” However, the department’s response did not explain why Houchens did not wait for backup to help de-escalate the situation, or why investigators did not interview Gonzalez, among other questions in Aguilar’s report.

Concluding its responses, the CPD rejected six out of Aguilar’s nine recommendations to help increase community-police transparency and accountability, including “lowering the probable cause standard to reasonable suspicion when determining whether to refer complaints to the Commonwealth’s Attorney,” “updating UOF/RTR [use of force/response to resistance] to include explicit identification and handling of pre-assault indicators,” “retraining [Houchens] of de-escalation techniques,” and “revisiting how much information is made available to complainants of misconduct.”

The department argued that “the discretion is up to the Chief of Police regarding a criminal investigation,” and “pre-assault indicators vary from person to person if known.” All officers have already “undergone substantial de-escalation and Crisis Intervention training,” and complainants are not granted access to body-worn camera footage and other evidence during an ongoing investigation, unless the chief allows footage to be released, claimed the department.

Additionally, the CPD disagreed with Aguilar’s recommendation that City Council consider how public intoxication policies can have a disproportionate impact on vulnerable communities. “We cannot excuse one class of individuals of their illegal actions and immediately turn around [and] charge another for the same crime based on social class. This would be considered a bias-based policing claim,” reads the response.

On November 3, Fogel issued his response to both Aguilar’s report and the CPD’s rebuttals. Though the attorney agreed the former director’s recommendations were worth consideration, he took issue with parts of the evaluation.

“There were several points at which he deviated from his own [prescription] to consider ‘whether the CPD thoroughly, completely, accurately, objectively, and impartially investigated’ the allegations of the complainant and not to ‘reinvestigate the interaction,’” explained Fogel. “His finding that there was probable cause to arrest C.G. for drunk in public under the state statute speaks to a conclusion, not an inquiry into the investigation.”

The attorney questioned why the CPD did not want Houchens’ interview to be released to the public. “Why is this statement subject to secrecy? Because it acknowledges that he makes an effort, when he gets calls, to ‘get them out of the public view . . . [and] just not on the mall.’ This is significant evidence that the arrest was for not leaving the mall, not because C.G. was a danger to himself or others,” said Fogel.

Fogel also slammed the department for rejecting most of Aguilar’s recommendations “without a logical, or even any, explanation,” particularly regarding information provided to complainants.

“Without disclosure of the evidence upon which the CPD relies, there is no opportunity for the complainant to know or challenge the accuracy of IA [internal affairs] determinations, or for the public to have confidence in the IA process,” claimed Fogel. “There was no reason for CPD not to provide the complainant with all of the evidence that IA relied on except for its culture of secrecy.”

When asked how the city planned to move forward with Aguilar’s evaluation and recommendations, Mayor Lloyd Snook said that he did not know what would happen next— “This is all new!” he wrote in an email.