“We want to not have data like this,” Katina Otey said candidly at the February 2 Charlottesville School Board meeting. The chief academic officer’s presentation on student conduct revealed a troubling trend.

“A majority of [conduct violation] incidents were committed by Black students,” she said. “And male students.”

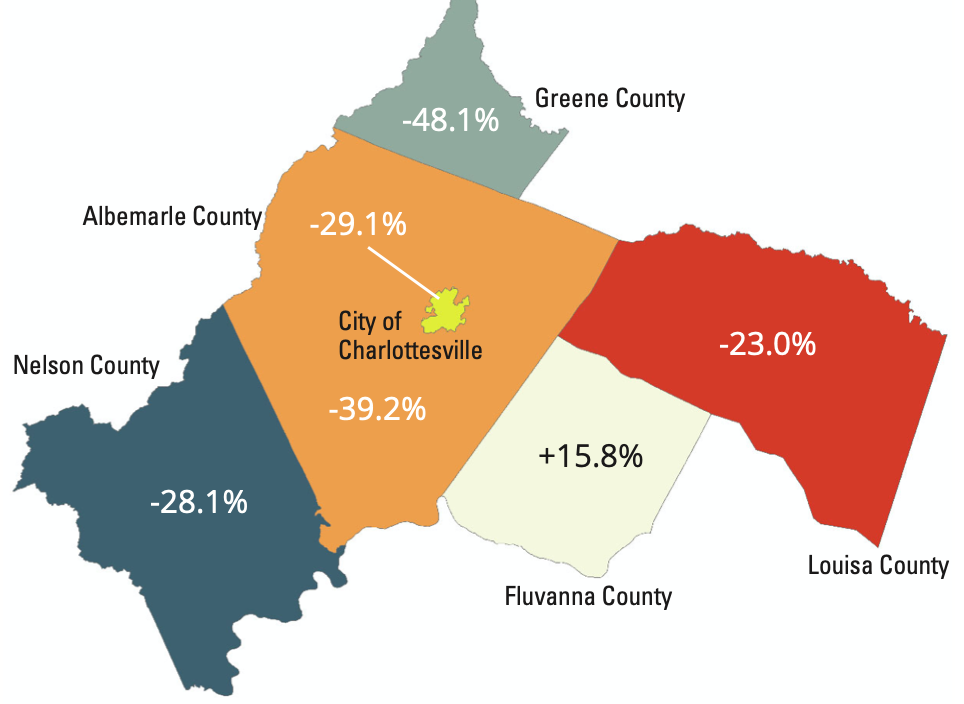

Seventy-seven percent of students suspended in Charlottesville City Schools this school year were Black, despite Black students constituting 28 percent of the student body. Conversely, white students make up 40 percent of the student population but only 4 percent of suspensions.

Black kids being disproportionately punished is a national trend, but some school board members hoped that removing school resource officers would rectify this. Several CCS representatives argued that parents and the community have a role to play.

“There’s a lot of undue burden on counselors and teachers to deal with a wide array of different problems,” said student representative Vivien Wong. “There’s not enough bandwidth to deal with every student’s concerns.”

Board member Lashundra Morsberger concurred, noting that “a lot of the conditions of your life if you’re a young Black boy or girl … are a consequence of being Black here in Charlottesville.” Morsberger argued further that “these things are generational and deep” and there is no “quick fix.”

Regardless of the root cause, parents remain concerned about violence in schools after a brawl at Charlottesville High School was filmed last week. Tanesha Hudson called out board members for being “unable to control the school” and alleged that students can easily leave campus without permission.

Superintendent Royal Gurley gave an impassioned speech, “debunking” that the schools are “out of control,” and asking “if the community is not holding the community accountable, what do you expect the teachers to do?”

“If you want to create this narrative that it’s about … what teachers are not doing, that’s absolutely not true,” said Gurley. “I’m not going to mince my words at all—I am holding students accountable.” The superintendent recounted an instance in which a parent refused restorative services. “You can only help people who want to be helped,” he stated plainly.

Board chair James Bryant repeated this call for accountability, asserting that “it takes a village to raise a child,” and “we have to have the parents and guardians come to the table as well.”

Activist and UVA student Zyahna Bryant said she also “would not mince her words.”

“We can pass the buck all day. Communities aren’t doing enough, teachers aren’t doing enough—what are the practical asks? And where do we meet in the middle?”

The CHS alum, who was instrumental in the removal of the Robert E. Lee statue, acknowledged that the district could not fix systemic racial inequity in Charlottesville but implored the school board to focus on tangible results.

“I don’t think anyone is asking for the school board to fix age-old issues of the community,” she said. “I think what we are asking for is accountability in terms of new policies, a sort of grading measure of how we’re doing with these new policies, and for the school board to take a strong stance on what the district represents.”

In a statement sent to C-VILLE, Otey clarified that the data was collected to “help schools handle situations with consistency and fairness,” and that they “are very mindful of the need to keep equity in the forefront when we are responding to behavioral issues.” Gurley wrote that the school board plans to “calmly and transparently acknowledge these behavioral issues” and “work with the community to find equitable solutions.” He also noted that the school board is not currently considering bringing back school resource officers, something Albemarle County Public Schools has flirted with.