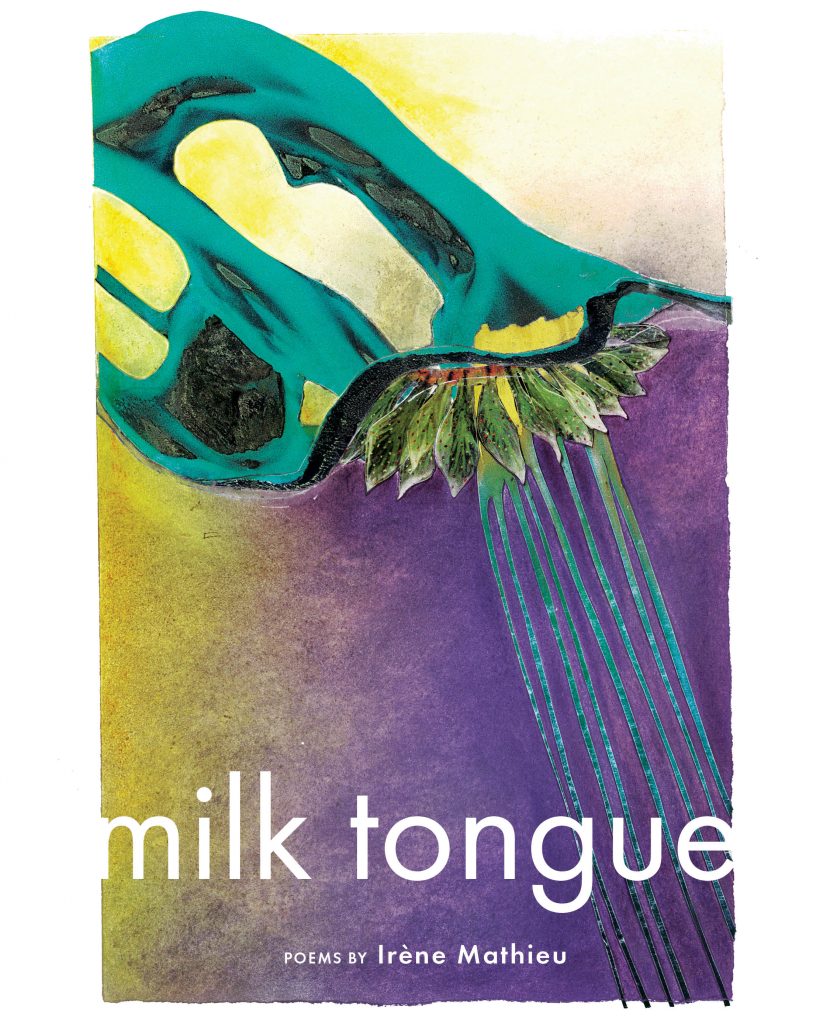

Poet, pediatrician, and public health researcher Irène Mathieu follows her three award-winning poetry collections with milk tongue, a new book of poetry.

Referencing the milky covering that can occur on an infant’s tongue after feeding, milk tongue is a collection that explores parenthood, family, and the intricacies of existence in this world, filled with Mathieu’s precise, embodied language. In “second attempt at going home,” Mathieu muses:

…here is one way to go home: find your brother, find a bench (any), pull the yarn out of each other’s throats until your language finds its hooves again, hear your common gallop over the land.

Playful with form, ranging from traditional Japanese haibun style to more experimental forms, Mathieu remains attentive to the physical space of the page, and committed to examining what it means to be human in the wild, in the world, as we experience climate collapse and other crises amidst the distinct pleasures and routines of being alive. In “clockmelt,” she writes:

…faith is the knowledge that this precise loneliness will circle back around at regular intervals divinable only by the rain that starts at midnight. in a midnight assemblé on my retinas, the future & irredeemable past blaze in and out of focus like this year’s three hundred wildfires—controlled only by the winds.

In “Labor Day,” she considers:

it’s hard work remembering to be human, and that’s what we’re here to celebrate today, with chlorine & grill at the edge of a wild we crave.

In advance of her upcoming book launch for milk tongue at Visible Records on May 6, we spoke with Mathieu about the forthcoming collection:

C-VILLE: In what ways has motherhood influenced or changed your writing practice, in addition to influencing some of the themes you explore in this collection?

Irène Mathieu: The poems in milk tongue were all written before I became a mother, but my writing practice hasn’t changed all that much since my daughter was born. My job as a physician doesn’t leave much time for large stretches of uninterrupted writing, so my practice has always been to jot things down in the margins of my days, and to delve into the work during small windows of time. Logistically speaking, motherhood has simply increased the intensity of that pressured way of writing. Although I wasn’t a parent when I wrote milk tongue (there are a couple of poems in it that I wrote while pregnant), this book very much arose from a sort of pre-parenting psychic space. That is, the book is evidence of my grappling with the ethics surrounding some of the mundane desires of adulthood, including the desire to have children, while living in a society in which inequality and separation from the greater-than-human world are foundational conditions.

What led you to the different styles and forms that show up in this book? Are there any that were completely new to you?

Haibun is a Japanese form that I came across early on in the writing of milk tongue. Traditionally these poems describe a journey, and they consist of a prose poem punctuated by a haiku-like stanza that contains some sort of key insight. A lot of my poetry is inspired by travel, but I was also thinking about the metaphorical journey that is adulting, so I found myself returning to haibun as a way to explore these themes. Other than the haibun, I was mostly experimenting with forms and styles I created as I was writing. I was really interested in how the way a poem is physically laid out on the page can add to its layers of meaning, and to the experience of reading it. I love that in this sense poetry also can be a visual form of art!

How does language meet the challenges of grappling with our warming days, diverging selves, and unreliable histories and futures? How does it fall short?

For me, language is a transformational medium. That is, through writing I discover what I need to (un)learn and how I need to grow in order to make more useful contributions to the world. Penawahpskek lawyer and activist Sherri Mitchell says that 80 percent of social change is visioning and creating the world we want, and I think writing is a tool to do that kind of imagining. Mitchell also has said, “[T]his rising tension [and] anxiety that people are feeling is not necessarily evidence that something is wrong, but perhaps is evidence that something is being righted within us.” Writing gives me a way to explore the tension I feel at this moment in history, and to figure out what is being righted within myself. When the language falls short of doing this work, for me it’s a sign of imaginational failure, and the remedy is generally to listen more—to ancestors, elders, young people, plants, and non-human animals around me—in order to feed my imagination.