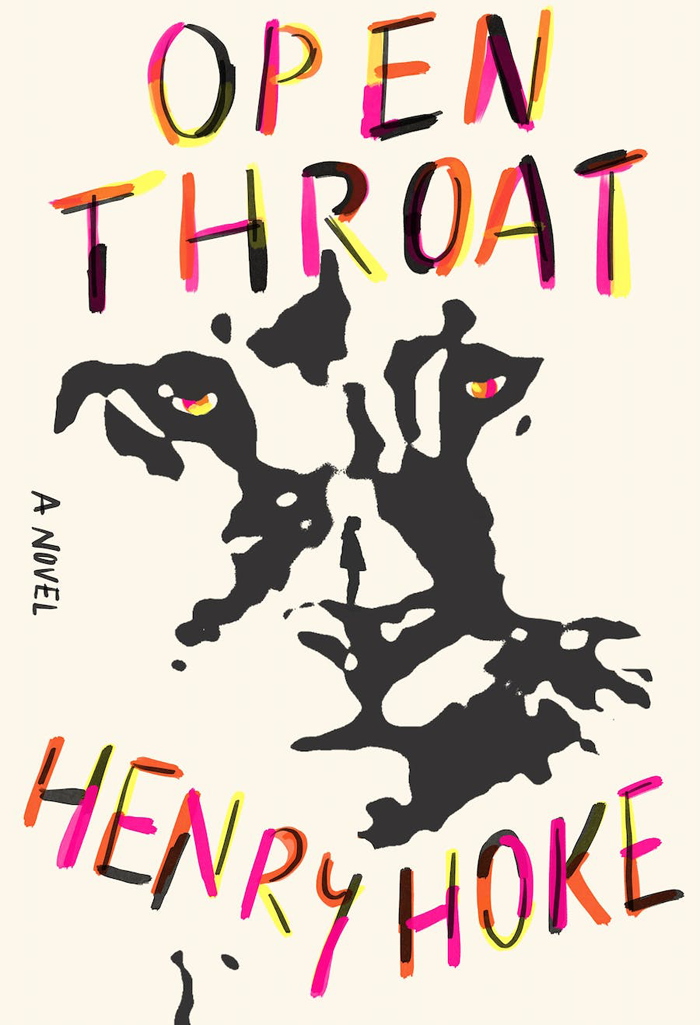

A queer mountain lion in “ellay” is the narrator of Open Throat, the new novel by Charlottesville’s own Henry Hoke. If that doesn’t pique your interest, we interviewed Hoke to take a deeper dive into his fifth book, which has garnered widespread attention and acclaim, and tops many of the year’s best-of lists.

C-VILLE: The mountain lion narrator of Open Throat has a name from their mother that is “not made of noises a person can make” and later comes to be called heckit. The character was based on the real-life mountain lion who was known by his wildlife tracking identifier number, P-22 (though Indigenous tribes found this too similar to dehumanizing numbering used in residential schools). Combined, this points to the power of identity-affirming names. How does your work explore this?

HH: The core of all my writing seems to be identity exploration, and the futility of truly capturing a place or being, whether it’s my infamous hometown, or the gender journey of a puma. I love how literary work can refract and warp our perceptions and allegiances. In my practice I tend to find some (often bizarre) constraint or conceptual approach as the engine for creation: a memoir of Charlottesville told through 20 stickers, or this feral animal voice to access and engage with the kaleidoscopic chaos of L.A. These approaches feel less authoritative, and more truthful to my limitations, which I strive to embrace.

As someone whose time in Los Angeles overlapped with P-22’s heyday, how did you experience that phenomenon, and did you have him in mind as a protagonist even then?

I always felt a kinship with the big cat, because we moved to L.A. around the same time—me coming south from my suburban grad school, him crossing the 405 freeway from the Western mountain ranges—and spent the better part of that decade roaming in parallel. I first became fixated on P-22 when he was found living under a house in my neighborhood. I thought how remarkable it is to have this apex predator chilling quietly, undiscovered, right on the fringes of L.A.’s wild urbanity.

Though this is an L.A.-focused book, the themes are universal: parental estrangement and chosen families, human destructiveness and despair, environmental disasters and climate collapse, and even the what-could-have-been of old crushes. Were these intentional or did they emerge along the way?

The lens of the lion really allowed all the environmental, societal themes to emerge organically, so I didn’t set out to thread those, just trusted they’d be present. And, of course, some larger story beats were based on P-22’s real-life journey (even the attack on a koala at the L.A. zoo). The family history, queer desire, and particular arc of vengeance were what I brought to the table and ran with, so those were the core for me as creator.

There’s also an undercurrent of exploring the tension between needs and wants when it comes to survival, personally but also from community and global perspectives. Why was it important for you to empower the lion to ultimately give in to desires?

My lion’s internal journey becomes one of accepting that, by prolonged exposure to people—our language and our encroachment on the natural world—they’re becoming a bit of a human themselves in regards to their own agency, accessing deeper desires, behaving against their own survival instincts. To quote heckit: “this is not about need / no this is want / it’s a terrible choice but I’m making it / just like a person.” It was fascinating to get inside the mind of a powerful hunter of an animal, who is still deeply out of control when it comes to their own circumstances, confused and isolated. There’s something deeply human about that struggle in this global moment. I think we all feel our impact on the world, but have no idea how to shift the destructive trajectory, to right past wrongs.

Thinking about the lion’s vocabulary that’s been gleaned from passing hikers, how do you think about oral tradition as a narrative device but also as a degraded aspect of life in the Anthropocene?

That’s a big, haunting question. Assembling meaning from fleeting, concentrated bursts of language emerges as my lion’s key mission, and curse. I felt, and feel, similarly in our era of full informational deluge, of attention spans slipping. This book is my first monologue, where I inhabit an uninterrupted first-person-singular voice throughout. In that way—and especially listening to the beautiful audiobook performance of my reader Pete Cross—I thought very much about carrying on a direct, oral storytelling tradition. A natural voice bearing witness, cataloging, and roaring out to whoever will listen and remember.

You mentioned in another interview that your editor encouraged you to add asides and digressions—like a reverie about when “all the people were gone”—as a way to add texture to the text. These are also some of the most hope-filled moments in the book, where the lion imagines a life less defined by isolation and “scare city.” What’s an unexpected wisdom that you’ve learned through writing this book?

That breathing room, gracefully allowed and encouraged by my editor Jackson Howard, was key in letting Open Throat’s potential bloom. The narrative intensity, the nonstop, was important in getting me through my drafts and getting it out there, but on the other side of the sale, it was such a gift to work with someone who prompted me to allow more air into the equation, to weave, to imagine even more. I learned that even in a succinct book like this one, there’s never a moment where it can’t sharpen or explode with focused revision.

Finally, what’s it like to have one of the most talked-about books of the summer, with an official T-shirt no less?

It’s been overwhelming! I’m attuned to and holding onto all the surreal moments of being known: Mia Farrow tweeting about The Washington Post review. Taking a Lyft home with the windows down and witnessing a group of people outside a closed Brooklyn bookstore pointing inside at my lion’s face. My U.K. publicist wore the T-shirt on the day of our London event, and a stranger approached him on the Tube to say how excited he was for Open Throat. Later that day, in a completely different neighborhood, we ran into the same stranger and I got to shake his hand. I may get burned out, but I’ll always be grateful for the booksellers and readers who’ve championed this wild story, and all the new friends I’ve made.