It wasn’t until the 1970s that painter Frances Brand found her creative calling. Inspired by the story of Anna Luisa Puerta, an immigrant from Colombia who took a job as VDOT’s first flag woman in order to support her family, Brand started thinking about other people in our area who were the first to do something noteworthy in their careers, studies, or other endeavors, whether because of race, gender, or nationality. Running with this idea, Brand completed over 157 portraits with the bulk produced between 1974 and 1978.

Painting History: Frances Brand and the “Firsts,” a panel discussion on Brand and an exhibition of her legacy of socially engaged artwork, will be presented at 6pm on Wednesday, January 10, at the Martin Luther King Jr. Performing Arts Center. The panel boasts its share of firsts—Nancy O’Brien (Charlottesville’s first female mayor), Cornelia Johnson (Charlottesville’s first Black female officer), Teresa Walker Price (the first Black female secretary of Charlottesville’s electoral board)—all painted by Brand, as well as Frank Walker (artist and painter of a portrait of Frances Brand). Former Charlottesville mayor Virginia Daugherty will serve as the event’s moderator.

The panel, and exhibition of a selection of Brand’s portraits on view in the performing arts center lobby, is part of a larger effort undertaken by Daugherty, O’Brien, and others, to ensure the “Firsts” portraits remain a vital part of the Charlottesville community. Brand’s granddaughter, Cynthia Brand, donated the collection to the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society in 2006. Many are in need of costly restoration work. Brand didn’t use the best materials, sometimes painting over affordable artwork from five and dime stores.

Brand, who died in 1990, was wonderfully unconventional. An Army brat, whose father, maternal grandfather, and maternal great-grandfather all graduated from the U.S. Military Academy, Brand was born at West Point. She moved from one Army post to another throughout her childhood, attending boarding schools, including a convent school in Belgium, before entering Goucher College in Baltimore.

Brand lived in Charlottesville twice. The first time while her husband was attending law school in the late 1920s, and then she returned for good in 1959, settling in the JPA neighborhood. In the interim, she had two sons, joined the Women’s Army Corps, divorced, and lived abroad working with the German Youth Association aiding children who’d suffered under the Nazis. Upon her retirement from the Army in 1954, she lived in Mexico City, where she earned a bachelor’s degree in art.

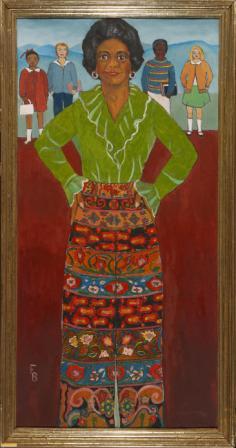

Brand’s deep commitment to portraiture and social justice is similar to her contemporary, the great Alice Neel. So too is the confrontational quality of her portraits, their scale, and the interest in pattern. Brand uses it with panache, as can be seen from the bold herringbone in the jacket of William Harris, UVA’s first dean of African American affairs; the black and gray houndstooth of The New York Times’ first female reporter Nancy Hale Bowers’ cape, which echoes the newsprint in her hand; and the elaborately embellished skirt worn by Grace Tinsley, the first Black woman to serve on Charlottesville’s school board. In Brand’s self-portrait, she employs the conceit of the mirror to give you two Brands: herself and her reflection, thus doubling not just her, but also the expanse of eye-popping floral material that comprises her gown, turning the bottom of the painting into a field of flowers.

Evident in the work of both Neel and Brand is the respect and admiration for their sitters. But that’s where the comparison stops. Neel was a consummate artist in complete control of her medium. She took her time developing a work to completion. For Brand, the narrative elements, and her goal of recording as many firsts as she could, eclipsed technique. She was in a hurry, eager to complete her project and trumpet the achievements of her sitters.

Brand didn’t just paint “the walk,” she walked it, not only by shining a spotlight on ordinary people doing extraordinary things, but in her inclusive attitude. It’s noteworthy that Brand, along with her friend, prominent local civil right activist Sarah Patton Boyle (who Brand depicts with a burning cross that had been ignited by white supremacists on her lawn), are the first white members of Charlottesville’s NAACP.

We don’t often have the opportunity to pause and consider steps made along the way that help enrich a community and move it forward. Brand’s joyful paintings of this extensive cast of lively, interesting, stylish, and socially engaged people offer just this, breathing life into a slice of Charlottesville’s history.