“To tell you about the beauty, I must also speak of threat,” writes Greg Wrenn in Mothership: A Memoir of Wonder and Crisis. A complex exploration into personal and ecological trauma that also investigates alternative healing and the cultivation of wonder, this book is as much a prompt for personal reflection as it is a call to climate action.

A survivor of childhood abuse, Wrenn spent decades in denial about and dissociating from his trauma. Much of Mothership is focused on processing relationships (especially that with his mother) and attempting to come to terms with his past. “It felt impossible to write about climate change without discussing my upbringing, to meditate on our future without thinking about my past,” he writes. “Denial leads many Americans to tell themselves pollution is a sign of progress and climate change is a hoax. It leads perpetrators to rebrand abuse as no big deal. … Whether we’re talking about abusers and victims—or people and the planet—it’s all part of what’s known as our extraction mindset.”

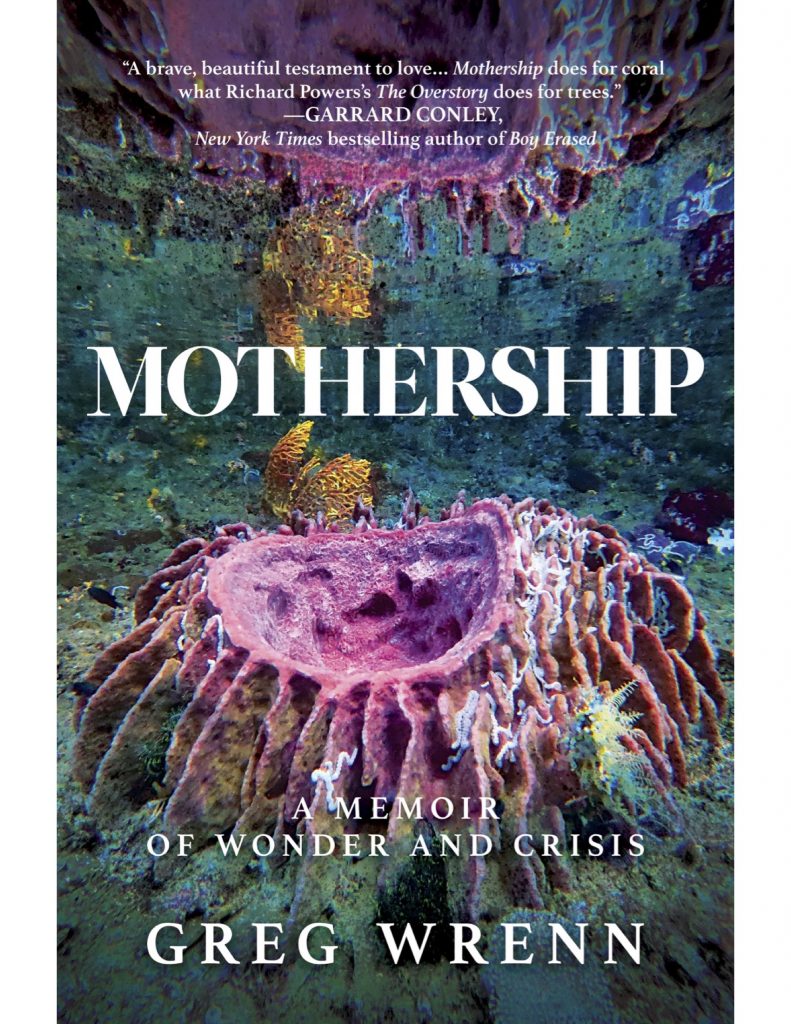

Built on a series of experimental eco-essays that Wrenn composed before he fully undertook the work of trauma processing, Mothership is rooted in his formal education as a poet as well as a love of nature. A self-described citizen scientist, he first explored coral reefs on a fourth-grade snorkeling trip in the Florida Keys, and has taken countless diving trips since, including repeat visits to the Raja Ampat Islands of Indonesia, which he describes in detail. Still, when sharing these experiences in his initial essays, he says he “wrote from that place of [environmental] concern, but wasn’t ready to make it personal yet.”

This avoidance aligns with his earlier work. “For me, poetry was an escape,” says Wrenn. “I hid behind symbolism and metaphors. In the kind of poetry that I was trained to write, fragmentation was praised … and a traumatized brain struggles to tell a story about the past because it is in fragments. For some, it’s a craft element but, for me, it’s my lived experience.”

That shifted when Wrenn began participating in ayahuasca ceremonies as a way of coping with suicidal ideation and addiction that resulted from C-PTSD (complex post-traumatic stress disorder).

“Ayahuasca helped me shift my identity from that of a poet to that of a prose writer, from a victim and an addict to someone empowered, who took responsibility for my brain … and in taking that responsibility, I realized I had a story to tell,” he says. Combining earlier essay themes with newer memoir work in Mothership, Wrenn reflects on the ways that silent meditation retreats, forest bathing, and medicinal use of psychedelics kept him alive and helped turn his attention to global concerns of impending climate collapse.

Indeed, after enduring ineffective attempts to address his trauma through talk therapy and psychopharmacology, Wrenn’s journey with ayahuasca led to dramatic change. From his first experiment with DMT, “in Tennessee at a multiday gathering of Radical Faeries, a group of back-to-nature queer folks,” to more focused medicinal use of ayahuasca at more than 30 private ceremonies held in places as varied as a Peruvian retreat center, the D.C. suburbs, the Amazon, rural Virginia, the Catskills, and—perhaps most stereotypical of contemporary ayahuasca culture in the U.S.—a Brooklyn loft. Wrenn reflects, “I was a patient, not a thrill-seeking tourist blind to the realities of cultural appropriation.” He expresses conflicted feelings about the colonialist power structures that are part of ayahuasca use among many, while nonetheless relying on these very structures for his own healing. However, he sees this as necessary after all other attempts to recover failed. “In healing myself, what awakened in me was the need for us to heal the planet,” he says. “So many of us receive healing from nature and it only seems fair that we should return the favor. … What we’re facing amounts to global C-PTSD.”

Alongside statistics about the severity of the climate cataclysm humans have wrought, Wrenn’s literary lyricism infuses Mothership in poetic phrasing and devices, including a chapter written as a letter to Adara, his “seventh or seventeenth great-niece,” a nod to the Iroquois’ Seventh Generation Principle. Here he grapples with one of the core ethical questions of our times. “As coral elsewhere is bleaching and dying, I’m here to document reefs that are still healthy and gorgeous,” he writes. “My carbon from my flights on this trip will melt Arctic sea ice about the size of my office.” Wrenn continues, “I did that to you, Adara. … No apology I could offer would be enough, but I want you to know I’m sorry. Sorry and ashamed you inherited the planet you did because of our inaction.”

Without looking away from the complicated and dark reality of climate collapse, Wrenn’s work is a project of inspiring wonder, sharing the beauty of reef ecosystems as a reminder to care. In this, he conjures coral textures and fleeting flashes of fish. He evokes an awe in the world, which might be more ephemeral than we know, if we continue to live with an extraction mindset.

“I tell myself, etch the shark and the coral into your mind’s eye. Hold these memories close like the philosopher’s stone for when you’re an old man and the ocean isn’t the same,” writes Wrenn. “Share them with anyone who will listen and believe.”