If you lived in Charlottesville in the early ’90s, you’re probably familiar with Steve Keene’s art. Keene worked as a dishwasher at Monsoon Café, which opened on the Downtown Mall in 1992, and owner Lu-Mei Chang gave him free rein to paint the walls, tables, and chairs.

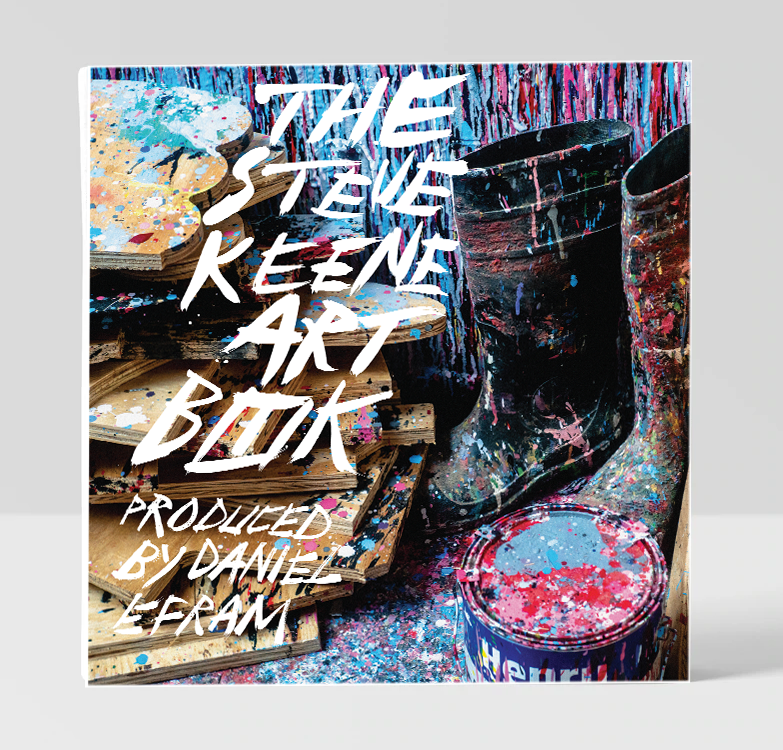

Chang’s early efforts to promote Keene are immortalized in an essay by her daughter, Elle, which appears alongside terrific pieces by Sam Brumbaugh, Shepard Fairey, and Ryan McGinness, among others, in The Steve Keene Art Book, produced by Daniel Efram.

Efram spent six years gathering material from art collectors, friends, and associates of Keene’s to create this comprehensive survey of his career. The book comprises 265 pages, over 200 of which are images of Keene’s work drawn from more than 600 submissions from around the world.

Spencer Lathrop of Spencer’s 206, a funky second-hand CD purveyor and coffee shop that was situated on the ground floor of what is now Common House, was an early Keene promoter. At Lathrop’s comfy, casual, and authentically hip establishment, you could browse the selection of used CDs, or get a coffee and sit in one of the mismatched chairs by the plant-filled window.

Along with the coffee and CDs, Lathrop had bins of Steve Keenes for sale. In nice weather, he’d move the bins outside with an honor system box where you’d slip in the money. The paintings, almost always on plywood panels, cost a dollar, sometimes two.

I was drawn to the unusual flickering quality of the paint and arresting subject matter paired with enigmatic titles. And the price was right. As I filled up my arms, shelling out the requisite bills, I didn’t think much about the work beyond its aesthetic appeal (which has held fast all these years). I was not alone. You began to see Steve Keene paintings popping up all over Charlottesville. To paraphrase Keene, it was bleeding into the landscape. “I was obsessed with leaving a mark, leaving a trace of me,” says the man whose goal was to be the Johnny Appleseed of art.

After his wife, Star, finished architecture school, the Keenes left town and the continuous supply of paintings dried up. The couple had been immersed in Charlottesville’s music scene and had UVA student friends who’d go on to form the bands Silver Jews and Pavement. In New York, they were swept up into the burgeoning indie music scene. “The music world was my world,” says Keene, 64. “That was our community, and so my art kind of mirrored that community.” The Steve Keene Art Book captures the era’s atmosphere with vivid descriptions of the Threadwaxing Space, an alternative art and live music venue in downtown Manhattan that “was regularly packed with Keene’s bright, inexpensive paintings, and everyone bought one—or five.”

While continuing to make his art, Keene worked with musicians on album covers and merch. He also continued painting portraits of album covers, an ongoing project commenced during his days as a DJ at WTJU. As the book points out, Keene has always painted pictures of pictures, or more precisely, pictures of the simulated world, selecting images that were designed to be seen. Knowing this, you can see the particular appeal of album covers.

It’s tempting to label Keene’s work as outsider art or visionary art on account of its DIY, raw, manic quality. But Keene holds an MFA from Yale (he went to VCU for his BA). Far from being a naïve artist, Keene incorporates conceptualism, installation, and performance art into his work. His low prices and enormous output is a revolutionary act, defying the established art world with its preciousness and “the ‘pickled’ coolness” of its denizens, ensuring that his art is accessible to nearly anyone. To date, Keene has produced over 300,000 paintings. But for the artist, it’s been one big painting. “The individual plywood panels are just puzzle pieces that together make up one great masterpiece,” he says.

Keene’s Brooklyn studio is a large cage of sorts, constructed of cyclone fencing that provides 80 linear feet in which to work. He paints assembly-line fashion on plywood boards hung in multiples on the fencing, producing the same image simultaneously.

He moves down the row adding the same dab of paint until he reaches the end. Going back to the beginning, he takes another color and repeats the cycle, over and over until the group is completed. Though the image is the same, the works aren’t identical; variations occur as he goes down the line.

He paints eight hours a day, five to six days each week. It’s physically demanding and obsessive. On an average day, Keene runs through five gallons of latex and acrylic paint and produces about 50 works. “It’s like making a hundred pizzas or a hundred birthday cakes at the same time,” he says. And when he finishes painting, the job’s not done—Keene packs and ships about 18-20 orders each week.

Though he’s garnered plenty of attention, with museum exhibitions in Cologne, Germany, and Melbourne, Australia, as well as Los Angeles, Houston, and Santa Monica, along with appearances in Time magazine, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and on NPR, Keene has never cashed in in the way art stars Damien Hirst and Jeff Koons did. His model of cheap multiples doesn’t support their kind of revenue.

Keene is after something more enduring than money, and he may just achieve it. Certainly, The Steve Keene Art Book goes a long way toward elevating his profile and providing context for the prolific artist.

Keene considers the demand for his work an affirmation and enjoys hearing where his paintings end up, such as the late Dennis Hopper’s L.A. bathroom, and in the hands of influential New York Times art critic Roberta Smith.

Original Steve Keenes can still be ordered from his website stevekeene.com. For $70, he’ll send you a random selection of six paintings, sometimes more. There’s a backlog of orders, but knowing Keene’s character and workmanlike approach, you’ll get them eventually.