Each day, we’ll have the latest news from the courtroom in the Sines v. Kessler Unite the Right trial. For coverage from previous days, check the list of links at the bottom of this page.

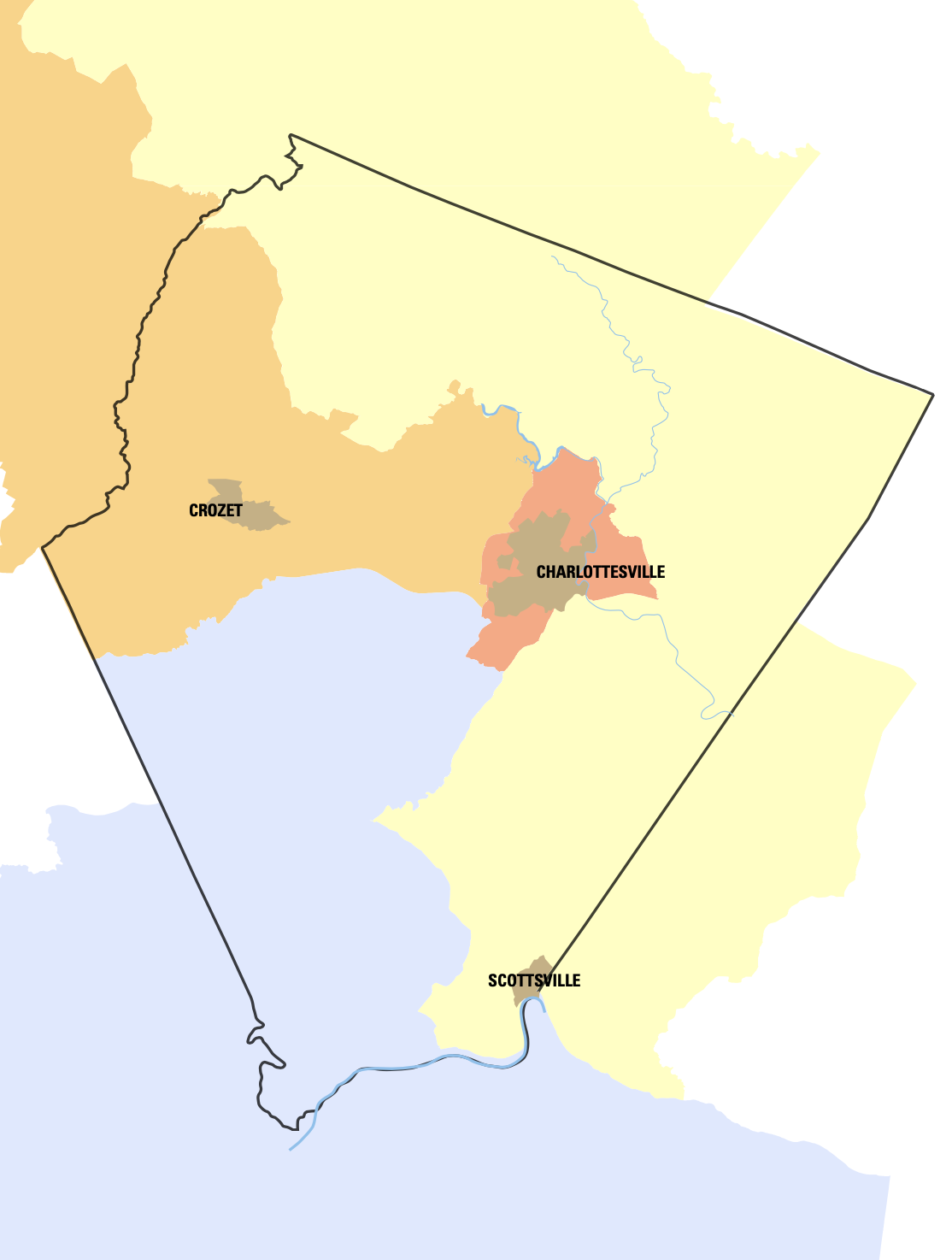

The difficulty of finding a jury without preconceived notions and biases about the Unite the Right rally here in Charlottesville continued into the second day of the Sines v. Kessler trial. The lawsuit, filed on behalf of nine plaintiffs, alleges a conspiracy among the white supremacist and neo-Nazi rally organizers to commit racially motivated violence when they gathered August 11 and 12, 2017.

It was after 6:30pm Tuesday when Judge Norman Moon decided to call it a day with only 10 jurors seated. He was willing to go with a panel of 11, but the defendants called for 12. Two more groups of jurors will be called in on Wednesday.

Other issues arose throughout the day. Attorney Edward ReBrook, working on behalf of defendants National Socialist Movement, the Nationalist Front, and Jeff Schoep, was in the emergency room, with no report on his condition by the end of the day. And the plaintiffs have a motion to reconsider a juror the defendants struck Monday, claiming the defendants’ challenge was made on the basis of race.

“I’m hoping we can get a full panel by noon,” said Moon, while acknowledging opening arguments may not be able to proceed Wednesday.

Twenty-six potential jurors showed up at the federal courthouse. Some were dismissed for work concerns if seated for a four-week trial. Others said they had already formed opinions about both the defendants and the plaintiffs.

One woman identified the two parties in the case as “Black Lives Matter and antifa.” She also had a problem with the rights of “radical communists and atheists” to protest. Moon dismissed her.

Another said her son’s after-school teacher was “Mr. Dre,” whom the judge concluded was DeAndre Harris. Harris was severely beaten in the Market Street Garage. She began to cry on the stand, and Moon said he was striking her for cause as well.

“I never liked protests. I felt like everyone should stay home,” said a third woman, who was struck for cause. Asked whether she could set aside her preconceived notions about protesters, she ballparked her odds at 75 percent.

One potential male juror said, “I am biased against the defendants. I believe they’re evil and their organizations are evil. I would find that difficult to set aside.”

“Crying Nazi” Christopher Cantwell and alt-right leader Richard Spencer, who are both representing themselves, wanted to question the man further after Moon was ready to dismiss him. That led to defense attorney James Kolenich lamenting pro se litigants, and said they could be prejudicial to his clients. Kolenich represents Jason Kessler, Nathan Damigo, and Identity Evropa.

A civics teacher who called the defendants “heinous” said he thought he could be fair. That was too big a leap for Moon, who struck for cause again.

One man called the left “unhinged” and said he believed the plaintiffs “probably” were armed. Another said, “I have already made up my mind. I live in this town. I know people who were assaulted. That poor girl died. I’ve already made up my mind.” Both were excused with cause.

At the end of the day, the court had seated three jurors: two men and a woman. Jury selection will continue into Wednesday.

Previous Sines v. Kessler coverage

Pre-trial: Their day in court: Major lawsuit against Unite the Right neo-Nazis heads to trial

Day one: Trial kicks off with jury selection