Things have changed a lot since Ricardo Preve arrived at the bus station in Charlottesville in 1977 without money or a passport. There weren’t many Latinos in town then, and he found the locals welcoming, if ignorant about Latin America.

“It was so easy to become a citizen in the ’80s,” recalls Preve. When he became eligible for American citizenship, his boss called his congressman, who called a federal judge, and Preve was sworn in the next day. “I think the whole process took 48 hours from beginning to end.”

Now, he says, there’s no path to citizenship, and the current waiting time for a Mexican is 22 years.

“I feel the attitude toward foreigners has changed,” says Preve, who was born in Argentina. He cites September 11, 2001, January 6, 2021, and August 12, 2017, as “moments that exacerbated and brought out things that may have been here, but were hidden.”

His latest film, Sometime, Somewhere, is “a reflection on my past after being in this town for 45 years,” he says. He uses Charlottesville to tell the story, not only of contemporary migrants, but of this country’s history of immigration.

Preve had an advantage many immigrants don’t have. His aunt, Countess Judith Gyurky, also an immigrant who fled Hungary during World War II, established a horse farm in Batesville. “They received me with open arms,” he recalls.

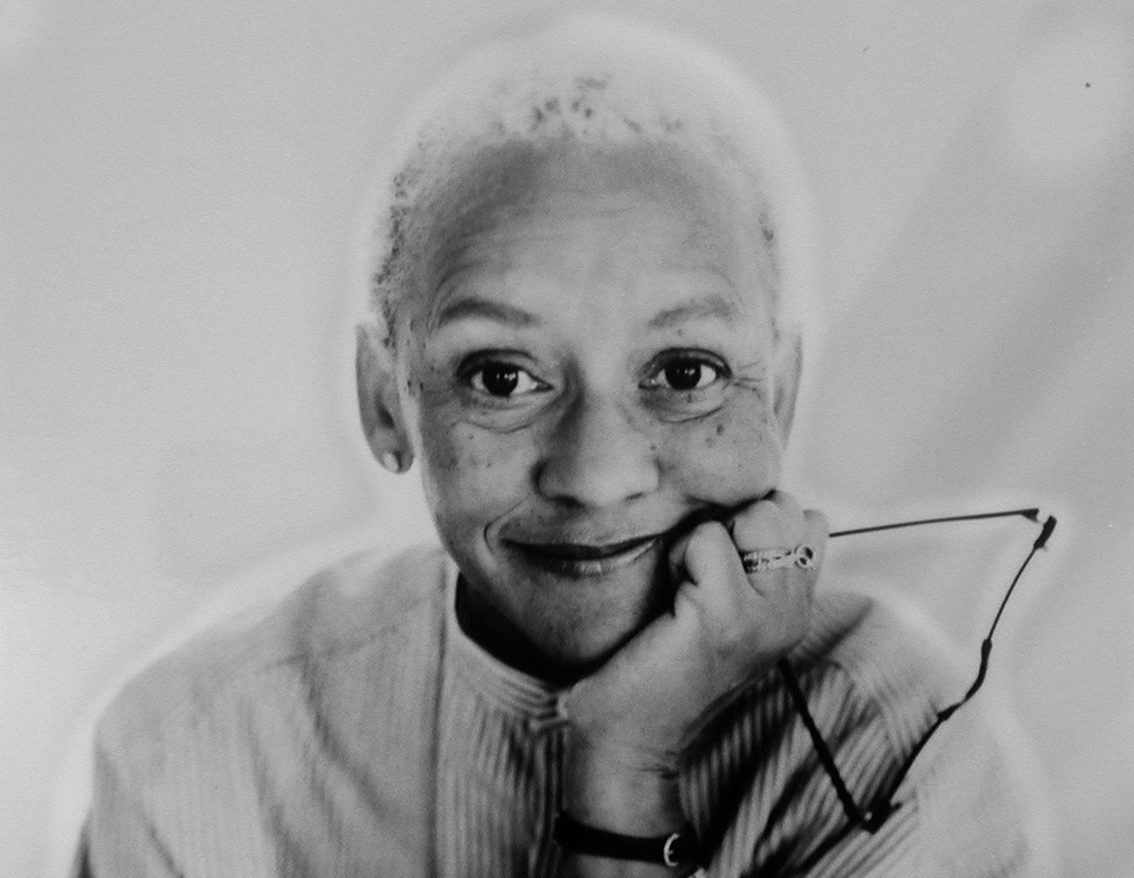

In Preve’s film, the forced migration of African Americans is remembered by Jamaican-born Andrea Douglas, executive director of the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center, at the University of Virginia’s Memorial to Enslaved Laborers.

The Irish also play a part in the local immigration story. Fleeing the potato famine, they built the Blue Ridge Tunnel in the 1850s. And on Heather Heyer Way, Preve films where white supremacy took off its mask.

Preve links The Grapes of Wrath’s Joads, who were escaping the Dust Bowl of Oklahoma, to the immigrant experience. “Substitute Garcia or Gonzales for Joad, and it’s the same story,” he says. “This is a repeating story in American history. People are exploited and they’re considered less than human.”

Preve didn’t ask about the immigration status of the people he interviews in the film, some of whom he found through Sin Barreras—Without Barriers—an organization that supports the Hispanic community.

“At first, people were worried I was undercover ICE,” he says. Then they heard his Argentinian-accented Spanish. “The rest of Latin America finds it amusing,” he explains. “It’s like a person from Alabama going to New York City. They realized we could not be undercover.”

The migrants and the immigration attorneys he talks to paint a dire picture of how the decisions to come to America are made.

“If you’re facing execution or starvation or rape, your choice is to either accept your fate or cross the border,” he says. “It is a death sentence to be a 15-year-old Salvadoran boy and the MS-13 says ‘either you join or die.’” Same for a young woman tapped to be a gang girlfriend.

He gave all the migrants the option to remain anonymous, and he was a little surprised at the number who gave their names. “I think that reflects a need for people to be humanized,” says Preve.

Preve, 66, made a career change in the early 2000s, moving from agroforestry to filmmaking. One of his earliest documentaries, Chagas: A Hidden Affliction, brought attention to a rampant disease that’s pretty much unheard of in the United States. Since then, he’s made almost 30 productions for television and film, most recently, From Sudan to Argentina.

Sometime, Somewhere is a more personal film for Preve. He tells film students at Light House Studio to pick a story they’re uniquely qualified to tell. “Immigrating from Latin America to Charlottesville is something I was uniquely qualified to tell,” he says.

And this story came with a special perk. “I got to sleep at home every night,” he says. “It was wonderful to stay in my hometown and shoot a film here.”

October 28 | Culbreth Theatre |

With discussion