Alex Garland’s newest film Civil War presents a vision of a war-torn, near-future United States that taps into many Americans’ fears of the worst-case endgame of ever-growing political divisiveness. It’s a promising idea, but this uneven movie is loaded with ridiculous plot holes, and despite delivering several impressive scenes, the film doesn’t maintain its level of quality.

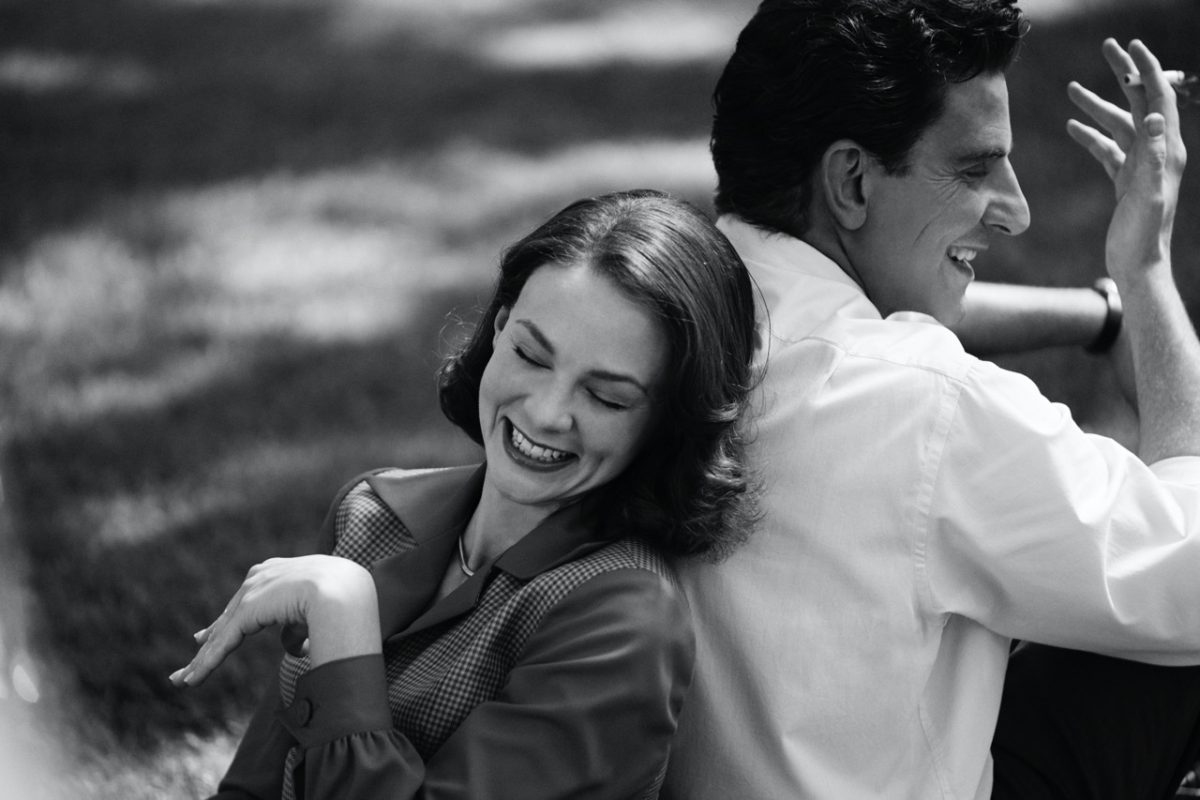

A few years from now, America is splintered into various warring factions that are never fully spelled out. Some of these groups are semi-realistic, Portland Maoists are mentioned, while others strain believability, and talk of a Texas-California alliance seems like pure fantasy. Within this hellish landscape, seasoned combat photographer Lee (Kirsten Dunst) and journalist Joel (Wagner Moura) set out for Washington, D.C., to land an interview with the president (Nick Offerman) before he’s captured and executed.

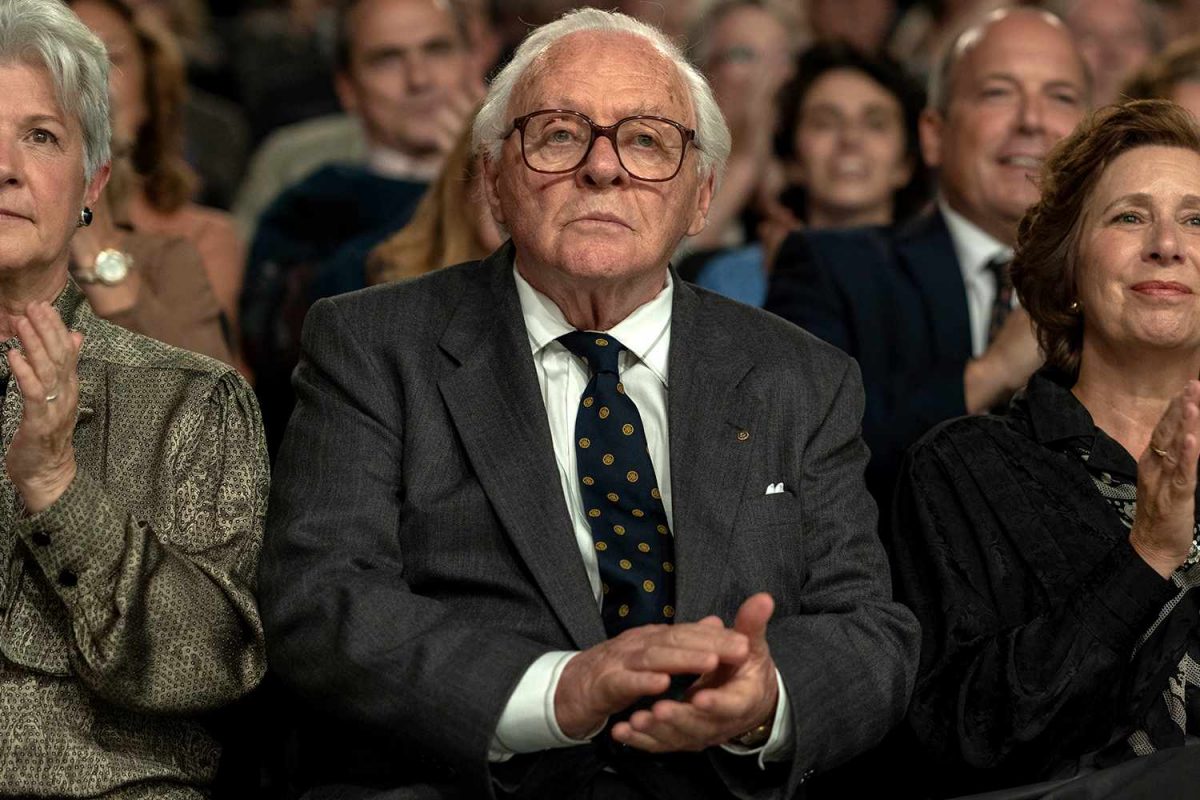

Following these two characters would make for a solid film, but, inexplicably, they bring along two companions on the dangerous mission: veteran journalist Sammy (Stephen McKinley Henderson), and aspiring photojournalist Jessie (Cailee Spaeny). Sammy is physically incapable of keeping up on the arduous journey, and Jessie is inexperienced, and they just seem shoehorned in to liven up the plot.

Civil War really shines when it depicts a war-ravaged nation devouring itself, including a key stop in Charlottesville. The film excels when it focuses on this nightmare intruding into the mundane: distant fires and tracer bullets flying over ordinary American buildings, a carwash turned into a torture chamber, or a wrecked helicopter in a JCPenney parking lot. Another strength is its little details, like how Lee buys gas with Canadian dollars, American money having become devalued like Confederate bills after the real Civil War.

Other high points are the tense, very bloody action sequences, including an encounter with two sarcastic snipers and the final assault on Washington, D.C. With only a few exceptions, the visual effects throughout are hellishly convincing.

Alex Garland is a frustrating filmmaker who never fully delivers on the promise of his films’ concepts. His movies are marked by intermittent scenes of real wit and talent, and long stretches where their plots completely disintegrate, as in the horribly muddled Men. Civil War is no exception. Seeing the vast American warzone through the photojournalists’ dispassionate—even cold-blooded—coverage was a sound basic concept, but injecting the two supporting characters was simply bad plotting. There are other significant flaws in the story, but revealing them would involve spoilers.

The cast is mostly fine, even when saddled with clunky dialogue. All the below-the-line talent on the film is first-rate across the board, including costume design, production design, makeup, and particularly visual effects. Garland and his team get bonus points for making unusual musical choices and not going for ironically traditional patriotic music.

Civil War deliberately avoids political partisanship, which will relieve some viewers and annoy others. This opaque approach doesn’t detract much from its quality, but it does point to an overall concept that’s too vague for its own good. There is so much about the film that better writers could have cleared up. But since this particular Civil War is so hotly divided between its virtues and its flaws, in the end, there’s no victory—just a draw.