Director-co-screenwriter J.A. Bayona’s Society of the Snow is a well-made, engrossing story of survival told straightforwardly and conventionally. The film deftly depicts a horrifying, real-life tragedy and, although it is vivid, it avoids being sordid.

In October 1972, Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 to Chile, carrying a rugby team of young men and some of their family members crashed in the frozen Andes mountains. With the plane slashed into two widely separated pieces, the survivors set about gathering what supplies they can and tending to the wounded.

Trapped in brutally cold conditions with minimal, claustrophobic shelter, their circumstances go from bad, to worse, to downright hellish. Faced with imminent starvation, they are forced to eat their friends’ and families’ corpses. Driven by an indomitable will to escape, they battle for survival within this merciless landscape.

This infamous incident is so captivating and shocking that it gets retold every so often. In the 1970s, the cannibalism angle made it prime fodder for exploitation in trashy movies like Survive! and luridly titled paperbacks like They Survived on Human Flesh! In 1993, the story inspired Alive!, an Irwin Allen-like disaster melodrama based on Piers Paul Read’s 1974 book of the same name.

In Society of the Snow, the survivors’ last resort of cannibalism is depicted very tastefully—no pun intended. This critical aspect of the story is effectively conveyed visually without morbid lingering. But be warned that the characters’ physical torments throughout are shown in graphic detail.

The story behind Society of the Snow may be familiar to many viewers, and while its innate power makes it gripping, the film isn’t nearly as affecting as it could have been. Bayona is faced with the difficult task of developing roughly two dozen characters, and he doesn’t entirely succeed—a challenge for any director within a standard movie’s running time—but as the survivors’ ranks diminish they get easier to follow.

The script is generally decent, with some outstanding sequences of the castaways distracting themselves from their plight by composing doggerel verse and practicing bird calls. But the opening scenes feature a ham-handed bit of foreshadowing as several characters attend mass and the part about eating flesh gets excessive emphasis.

The first act and the last act are solid, but the second act drags, which is arguably because Bayona wanted to convey the interminable quality of this situation. If that’s the case, there are more visually economical and engaging ways of getting that across.

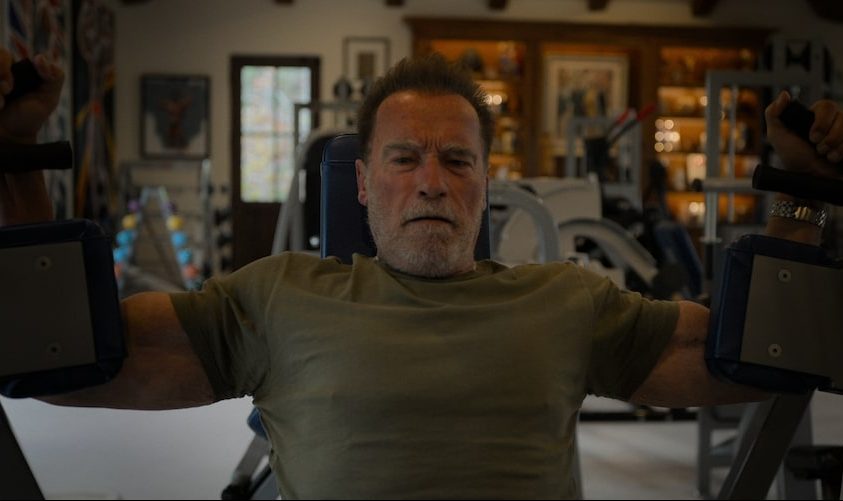

The makeup, art direction, and costume design work is first-rate, contributing significantly to an overall sense of gruesome verisimilitude. To further heighten the realism, the actors nearly starved themselves to look properly gaunt and malnourished, and the plane wreck was recreated in the actual area where Flight 571 went down.

The cinematography is fine, particularly considering how much of Society of the Snow was shot on location. Michael Giacchino’s score is excellent overall, proving once again that he’s one of the best film composers alive.

While not exceptional, Society of the Snow is a very respectable production, but not recommended for those with weak stomachs. If, however, you don’t mind taking this harsh journey, the film is ultimately satisfying and uplifting.