A driving force of the Cville Plans Together initiative has been to make sure the city changes its land-use policies to redress the past.

“Single-family zoning has historically been a tool to create and reinforce racial segregation in Charlottesville,” reads the Affordable Housing Plan adopted by City Council in March 2021.

The plan called for new zoning to allow “soft density” in single-family neighborhoods, “while limiting displacement of low-income communities.” The plan recommended identifying specific neighborhoods.

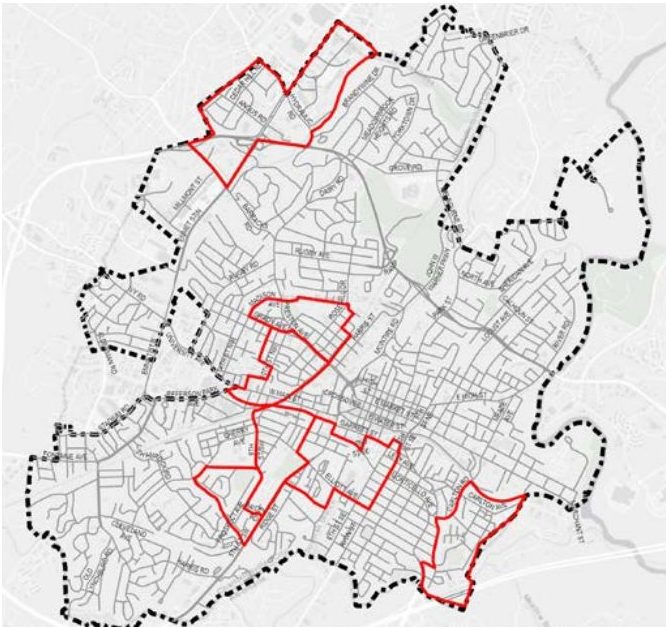

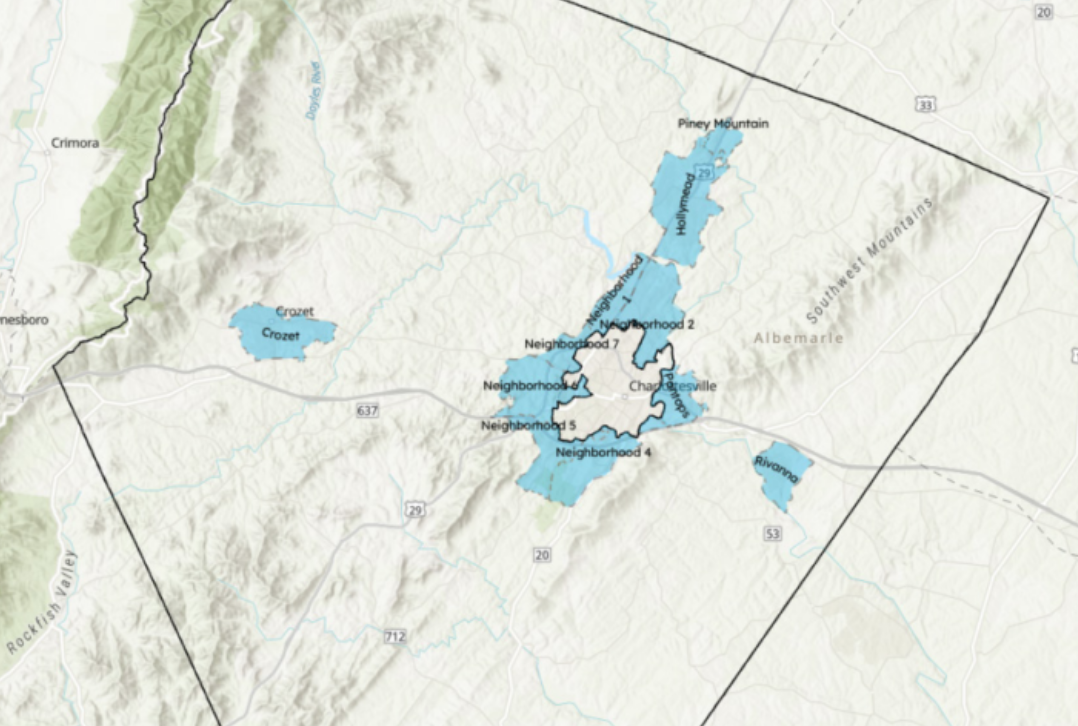

Eight months later, City Council adopted a Comprehensive Plan that includes a Future Land Use Map that called for the end of single-family housing in every neighborhood by allowing at least three dwelling units on all lots. This map also used census data to designate areas where there are more residents prone to displacement due to low incomes, as well as higher concentrations of Black households.

The plan called for new zoning tools and other policies for these “sensitive communities” to keep people in place and to support wealth building. The plan was clear that these areas were to be further outlined and that each might feature steps unique to that community.

Policy tools might have had funds to help pay for rehabilitation of owner-occupied homes. Potential zoning tools considered included allowing smaller lots and commercial uses, as well as more subdivisions and reduced parking minimums.

The Comprehensive Plan said the zoning rewrite should mitigate “the potential for displacement.” The Future Land Use Map also proposed restricting buildings in these areas to one unit per lot rather than the three allowed in all other neighborhoods.

Two neighborhood associations say the final draft of the development code didn’t meet that bar.

“All protection against gentrification and displacement has been surreptitiously removed in ways that were intended to hide its removal,” reads the letter from the Meadowbrook Hills/Rugby Neighborhood Association and Lewis Mountain neighborhood associations. “It’s clear that this was never about protecting those citizens in Charlottesville who are in greatest need for protection from development.”

As the zoning rewrite continued, the city did publish a document this spring that addressed these sensitive communities.

“We are working to determine the best path forward for supporting mitigation of displacement in the Sensitive Community Areas through the Zoning Ordinance in the context of the current draft, including affordability measures,” reads a portion of the four-page document, which goes on to say that more information about sensitive communities would be shared.

“We intend to share any updates to the strategies related to Sensitive Community Areas with the refined draft,” the document continues. Yet the phrase “sensitive communities” doesn’t appear in the final draft of the development code.

“After review, as well as focus groups with those who live and own in those areas, it was decided that land-use regulations were not an effective tool to address the needs expressed by the communities,” says Missy Creasy, the city’s deputy director of Neighborhood Development Services.

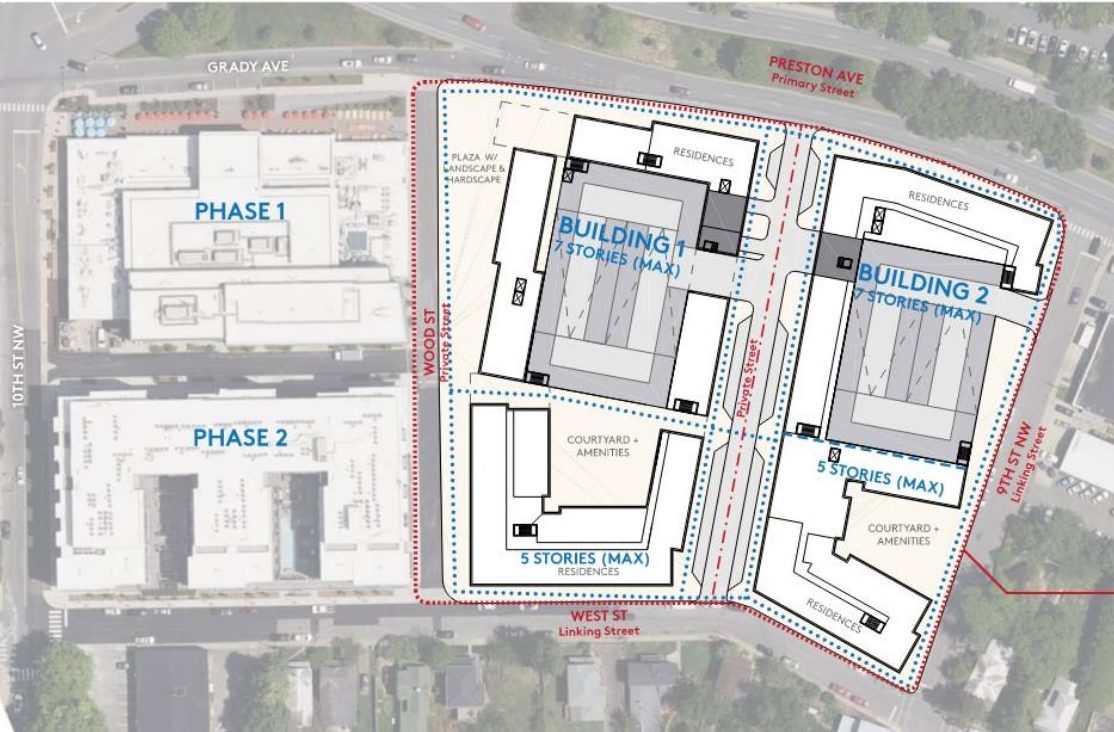

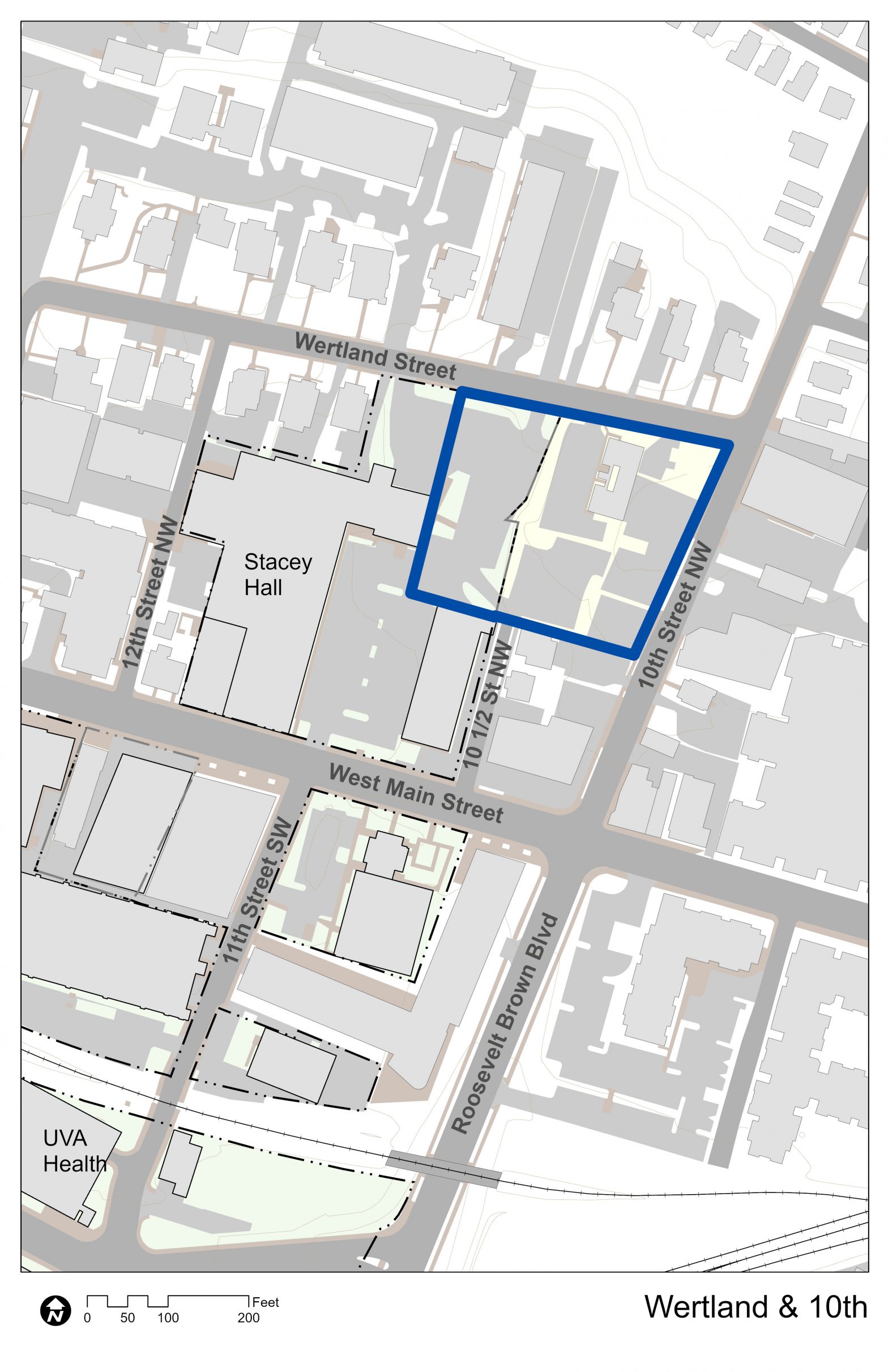

The city has followed through with other recommendations in the Affordable Housing Plan, such as putting at least $10 million toward affordable housing projects. This has included funding to Piedmont Housing Alliance for projects such as Friendship Court (recently renamed Kindlewood), and $5 million in funding to allow the Charlottesville Redevelopment and Housing Authority the dozens of affordable units known as Dogwood Housing.