By Alana Bittner

When writer and photographer Kori Price agreed to be part of the curation committee for a Black artists’ exhibition at McGuffey Art Center, water was not on her mind. It didn’t come up until someone asked how they wanted viewers to move through the gallery. Price recalls discussing ways to make viewers feel like they were underwater: “How did we want them to feel? Should they follow a specific route through the space? How should they flow through?”

Those questions evoked sobering scenes for Price. Water signified the Middle Passage, the expanse of ocean that was used for trans-Atlantic slave trade, into which an unknown number of Africans jumped rather than endure bondage.

But water is also present in moments of joy and release, strength and protest. Price says the committee, which also includes Derrick Waller, Sahara Clemons, Dena Jennings, Jae Johnson, Tobiah Mundt, and Lillie Williams, soon realized it was the perfect metaphor for framing such a broad topic, and agreed on “Water: The Agony and Ecstasy of the Black Experience” for the show’s title.

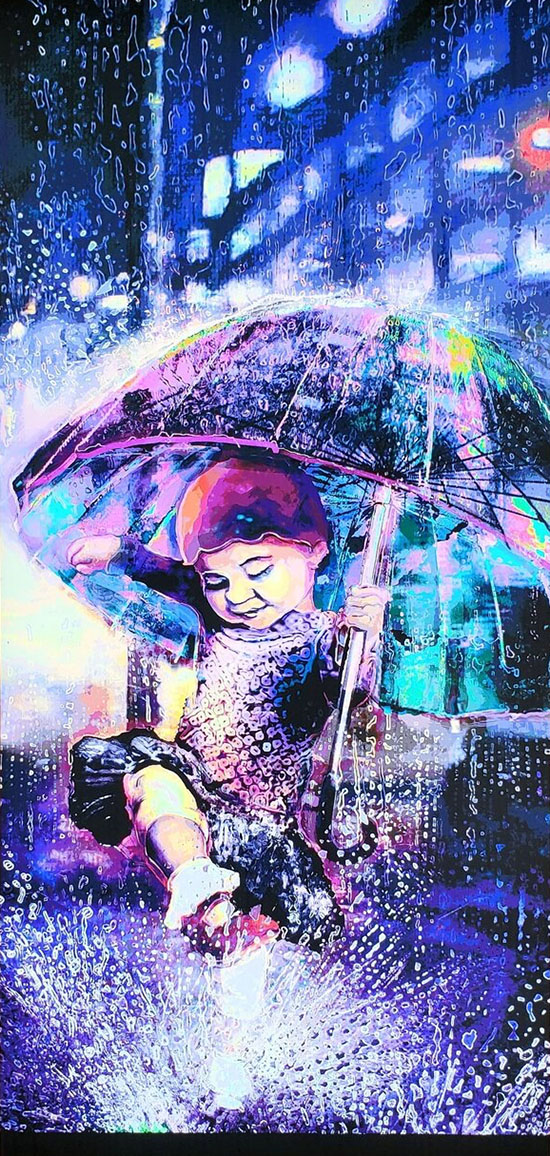

The group intentionally kept the requirements for the participating artists simple, asking only for interpretations on the theme. The results are wide-ranging and surprising. The show features painting, photography, and film, plus banjos carved from dipping gourds. In the films of Ellis Finney, water symbolizes the flow of time and memory. For painter Clinton Helms, the theme manifests as a powerful thunderstorm, while Bolanle Adeboye captures the joy of a young girl playing in the rain. Yet despite the range of subjects, Price marvels at how “each individual piece flowed together as a cohesive unit in the show.”

Waller, a photographer, says that initially, he had no idea where to begin in creating his art for the show. The challenge encouraged him to step out of his comfort zone and pick up a paint brush. The discussions involving the trans-Atlantic slave trade had imprinted one quote in particular on his mind. In Black Panther, Michael B. Jordan’s character Killmonger says, “Nah… Just bury me in the ocean…with my ancestors that jumped from the ship…cuz they knew death was better than bondage.” Waller’s resulting work, “Death Was Better Than Bondage,” is a haunting tribute to those who jumped. Black pins are scattered across a background as blue as the sea, marking the lives lost to the waves.

When Price discovered that the first slave ship to the mainland colonies, the White Lion, landed in present-day Hampton, Virginia, she grabbed her camera and drove down to visit. The experience was moving, and resurfaced questions about her own past. “Like many Black Americans, there’s likely not a record of who my enslaved ancestors were or when they gained their freedom,” Price says. “Though I don’t know them by name, I think about them…and wonder who the more than 20 Africans were that walked off the White Lion and became our legacy.” Price’s “Shadow of 20. and Odd Negroes” shows ethereal shadows cast upon a deserted beach, stretching almost to the ocean beyond.

As submissions came in, the McGuffey committee noticed that many of the participating artists were showing work for the first time. Waller says that in talking with the artists it became clear that opportunities for Black artists to show their work were limited. For Waller, this affirmed a troubling trend. In his experience, it’s been “very rare to attend an art show that is totally focused on celebrating the talents of Black artists.”

During the curation process, the committee members began to discuss the role they could play in helping Black artists get connected with opportunities to show their work, and eventually decided to present the show as the product of a new organization: the Charlottesville Black Arts Collective. Waller says that “helping Black artists gain exposure will be at the core” of CBAC’s mission.

“Water” shows just how valuable that exposure is. By featuring a variety of Black voices, the exhibit captures the nuances and multiplicities of the Black experience, something missing from white-domintated art spaces.

“I think that people can make a mistake in interpreting the Black experience as a singular and stereotyped experience,” says Price. She hopes viewers can “leave with a better understanding of our complexities.”

For Waller, “Water” touches on something fundamental. “I think the show will make people feel,” he says, “whatever that emotion may be…joy, sadness, anger, peace. I want people to feel. And then I hope these feelings spark good conversation and dialogue.”