Earlier this fall, I had COVID and, among its other health impacts, one bears mentioning here: For a time, I lost the ability to read. That is, I couldn’t read anything longer than a sentence without losing the rest of the day to a blinding headache. As a fervid reader, this was crushing. I spent a lot of time sleeping and then staring at a stack of books, wondering if I would ever read them. It got a bit maudlin. I’m now back in the world of readers and, to celebrate, here is a list of books from 2024 that I hope to read soon.

The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky by Josh Galarza

Josh Galarza is a Richmond-based writer and educator who’s currently completing his MFA in creative writing. His debut novel, The Great Cool Ranch Dorito in the Sky, was selected as a finalist for the 2024 National Book Award for Young People’s Literature, among other notable recognition. Accolades aside, I love a heartwarming YA novel and this one explores themes of mental health, grief, and body dysmorphia with empathy, quirkiness, and comics—and presumably a big handful of the titular chips in all their tongue-tingling glory.

The Practice, the Horizon, and the Chain

by Sofia Samatar

Sofia Samatar is a Roop Distinguished Professor of English at JMU and I look forward to reading everything that she writes. Her work is wide-ranging in genre, including speculative fiction, nonfiction about the craft of writing, memoir and family history, and more. Plus, her books offer interesting structural forms, lyrical prose, and deeply imaginative worldbuilding. She’s also prolific—this is just one of her two new titles this year. Like so much of the science fiction I enjoy, The Practice, the Horizon, and the Chain offers starships, transformative journeys, and a vision of the shared liberation that can come through collective action.

Cyberlibertarianism: The Right-Wing Politics of Digital Technology by David Golumbia

Before he passed away in 2023, David Golumbia taught at VCU and, before that, at UVA, where I had the good fortune of being his student. Intellectually rigorous and passionate about his work and the community it made possible, he left us this new, posthumous book that examines the right-wing legal and economic underpinnings of digital technology and how the early promise of the internet helped foster present-day fascism in global politics. Informed by expansive research as well as his experience as a software developer, this book argues that we have to understand where things went wrong before we can develop more egalitarian technological futures.

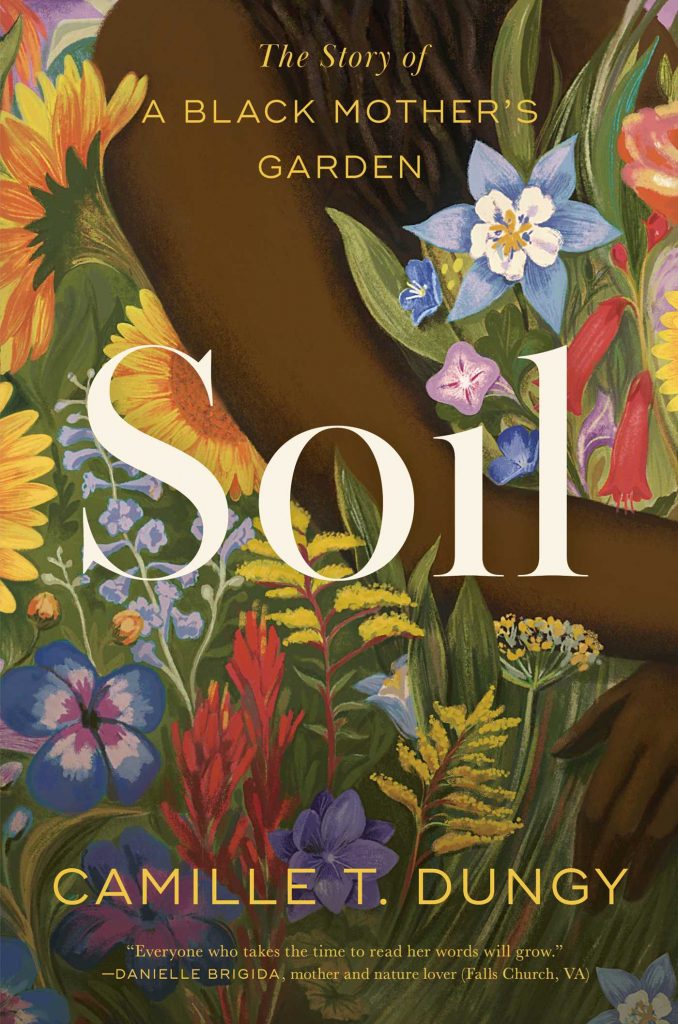

Soil: The Story of a Black Mother’s Garden

by Camille Dungy

This fall, Camille Dungy was the UVA Creative Writing Program’s Kapnick Distinguished Writer-in-Residence and gave a reading of her work. She is a poet and prose writer whose work often examines intersections between race, gender, the environment, history, and family. Among other honors, she was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and received the Library of Virginia Literary Award. Her latest book, Soil, shares her experience as a Black gardener and mother in a predominantly white town, examining how homogeneity harms our ecosystems and ourselves, while also interrogating how we relate to ideas of home.

The Sapling Cage by Margaret Killjoy

Margaret Killjoy is a transfeminine author, musician, and podcaster. Her community preparedness podcast, Live Like the World is Dying, is a mainstay for me, and her previous work includes short stories and novels that are darkly funny speculative fiction, bordering on horror at times. She gave a reading at The Beautiful Idea in September for her latest, The Sapling Cage, which is the first in a trilogy. This book promises to be more high fantasy than what I’ve read from her in the past, combining witchcraft, monsters, and magic in an epic, queer coming-of-age story that also tackles questions of power, identity, and gender. No notes.

Aster of Ceremonies by JJJJJerome Ellis

JJJJJerome Ellis is a self-described “disabled Grenadian-Jamaican-American artist, surfer, and person who stutters” who gave a performance of their work in October as the Rea Writer in Poetry at UVA. Their latest book, Aster of Ceremonies, is a poetic healing ritual, an invocation of ancestors, and a deft examination of race and collective belonging, reimagining what it means for Black and disabled people to take their freedom. Though I am typically a paperback reader, this audiobook is read and performed by Ellis, and I am ecstatic for the chance to listen while holding a hard copy in my hands, creating a harmonic resonance through his words.