Sprawling cinematic stories of drug abuse and crime sprees are nothing new. Martin Scorsese has honed this subgenre of brittle masculinity and confessional narration throughout his long career, and many others have tried to ascend to his platform for storytelling. Cherry never quite climbs to that rank, but it is an empathetic look at one man’s seemingly inescapable demise.

Directors Anthony and Joe Russo chose to return to their hometown of Cleveland, Ohio, with Cherry, though they arguably never left. Their previous films, Avengers and Captain America, used the Ohio location as a stand-in for larger, more expensive cities on screen. Heck, even Fate of the Furious was filmed there, so it is very likely you have been watching Cleveland for years without realizing it. This time, the Russos forego dressing up the city, and instead take a long, hard look at what it was in the early 2000s. Cleveland is tough and can be unforgiving, but it is not unworthy of its own moment in the spotlight.

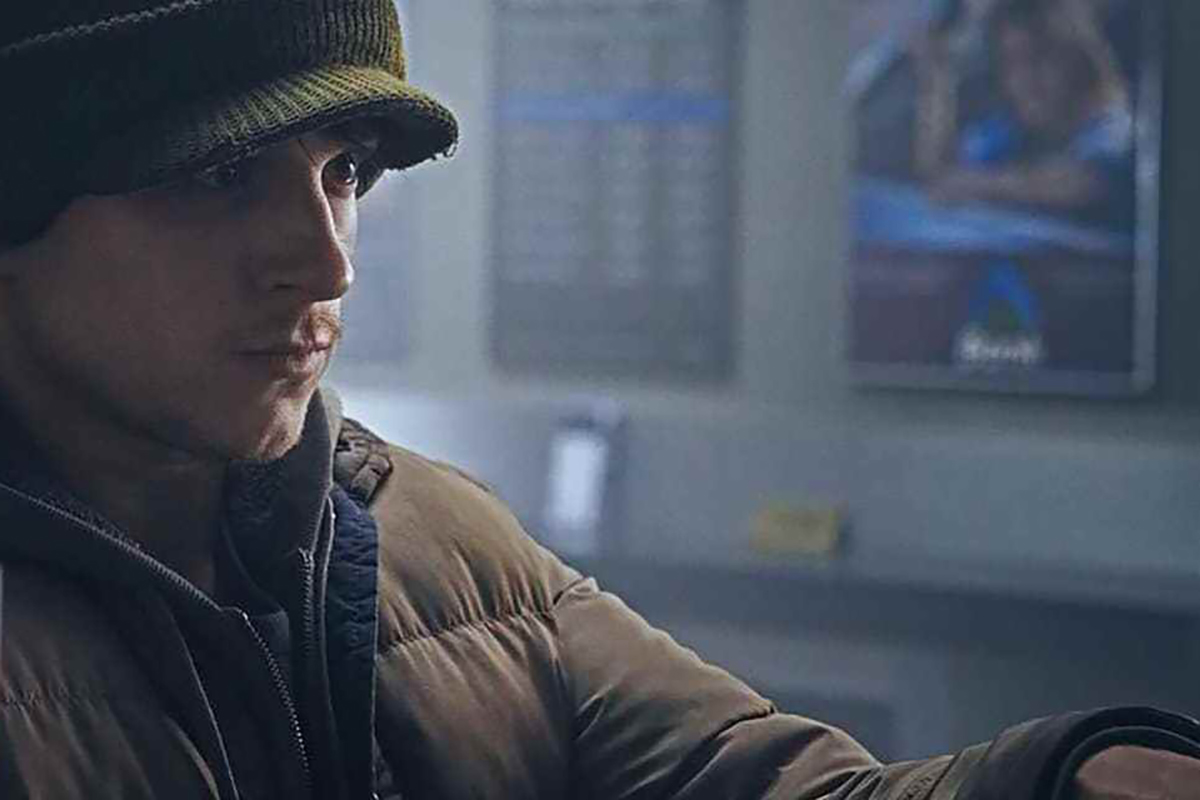

Tom Holland, with a wavering American accent, stars as Cherry, a young man who has fallen into a life of crime—when we first meet him, he is holding up a bank while explaining to us, via voiceover, how he goes about doing the job. No man starts out in life with a bandana around his face and a gun in his hand, and he takes us through the years that lead him to that moment.

If you haven’t already guessed, Cherry is a nickname, and the explanation of this moniker comes to us as we see him sink into his cozy criminality. Going back to his university days, he dabbles in drugs, and, in the midst of a most excellent ecstasy trip, Cherry meets Emily (Ciara Bravo).

Emily is a fellow student whose beauty is only matched by her fear of emotional vulnerability and commitment. During a wild overreaction to Cherry confessing his feelings for her, she says she’s moving away. His equally disproportionate response is to join the army and run from the woman who broke him, and the city that reminds him of her.

These different stages in Cherry’s life are divided by title cards, which let us know that Cherry is entering a new chapter. Not only do the Russos establish the mile markers along the way to call attention to the stages in the story, the film’s camera style, score, and even aspect ratio change from segment to segment. In college, the score is quaint, with almost cartoonish classical movements; basic training has more rock and roll; and Van Morrison takes the reins to steer us into Cherry’s life at war and away from home.

The film is brutally honest about the effects of war, and selectively dips into gore to prove its point. Considering how drastically this experience changes Cherry for the worse, it makes sense to show some of what will haunt him for the rest of his life.

Cherry never makes the argument that the main character’s descent into drug dependency or crime is inevitable, but it does make it feel inescapable. Each circumstance leads to the next, and before long, the next best choice for Cherry is to start robbing banks. He is not hopeless or flailing through his own hell, he is just trudging forward on an increasingly dark path. Cherry also stops short of ever feeling like a sermon or public service announcement. We see how awful war and chemical dependency is, but as with Cherry and Emily, those are lessons to be learned by experience and not instruction.

Accent aside, Holland brings this evolving character to life. Bravo adds some charm, but ultimately is given little to do besides stare adoringly, and it seems a disservice to try to measure her beyond that. The film does maintain a certain affection for Cherry’s love for Emily, connecting the dots to his swan dive into crime, but Cherry never excuses Cherry for what he has done.