The Charlottesville Police Civilian Review Board was among the key criminal justice reforms put in place following the 2017 Unite the Right rally. More than four years later, the board remains mired in controversy, with conflict between its appointed members and persistent legal questions about its powers hampering the board’s ability to keep law enforcement accountable to the city’s residents.

FOIAs and ‘flying monkeys’

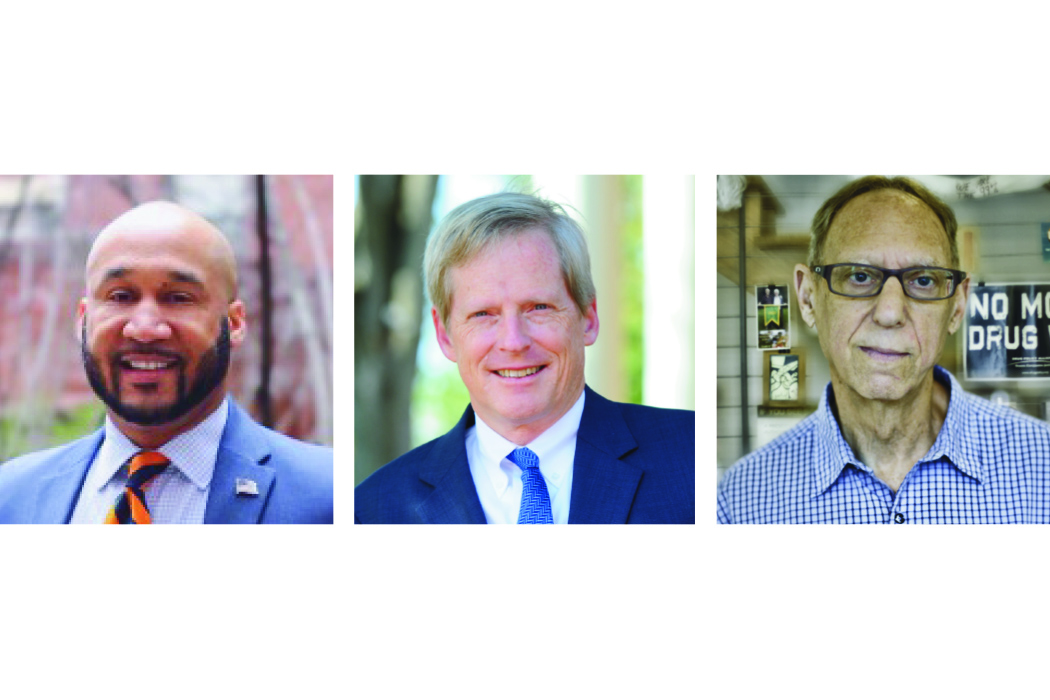

At last Thursday’s meeting, Bellamy Brown stepped down from his position as chair, shifting to a position as a regular board member. Brown’s 11-month stint as the CRB’s leader saw the body embroiled in multiple internal disputes. Text messages revealed recently through a Freedom of Information Act request by activist Ang Conn show the extent of the dysfunction within the board.

In August, Brown made a public statement calling for a change of leadership in the police department. Shortly afterwards, Police Chief RaShall Brackney was fired, sparking pushback from some in the community who felt she had been removed from her post because her efforts to reform the internal culture of the department had been too proactive. The Police Benevolent Association, a union-like coalition of police officers, had lobbied for Brackney’s firing, and Brown had met with PBA members over the summer.

During multiple text exchanges last fall, Brown and board member Jeffrey Fracher, a retired forensic psychologist, expressed their strong dislike for Brackney and then-mayor Nikuyah Walker. Walker had supported the police chief and disapproved of the firing.

“The mayor has done nothing to improve racist policing in 4 years except piss off a lot of people by running her mouth and playing to the white guilt of the [Showing Up for Racial Justice] crowd,” wrote Fracher in September. “She is a toxic combination of several personality disorders…So divisive, so cruel, so manipulative, so angry—all in the name of ‘racial justice.’”

“True story,” wrote Brown.

In September, Brown told Fracher he wanted Nancy Carpenter removed from the board. “She is a disaster. Is doing nothing for our mission. In bed with the flying monkeys,” replied Fracher. The following month, Carpenter sent an email to City Council and the board asking Brown and Fracher to resign.

Fracher and Brown strongly criticized Vice-Chair Bill Mendez for introducing a vote of no confidence against Brown during the board’s September 10 meeting. “He’s an activist at heart. His daughter who apparently supports Nikuyah could have gotten to him,” wrote Brown, referencing posts Mendez’s daughter made in support of Walker on Facebook in 2017.

In text exchanges with Fracher in August and September, member James Watson also said he hoped Brackney would leave the department, and expressed his disapproval of the vote of no confidence.

In addition, Brown criticized former city manager Chip Boyles for hiring Hansel Aguilar—and not him—as the CRB executive director. He claimed Aguilar, “a damn introvert and academic,” was not well-equipped to engage with the public.

In many texts and emails, Brown and Fracher discussed their disagreements with public commenters, particularly members of The People’s Coalition, a local criminal justice reform advocacy group, who they claimed were trying to control the CRB.

“I don’t think 5-10 people should represent themselves as representing the whole Black community. Especially when they are all, including Nancy, in the defund the police crowd,” Fracher texted Brown in September. “All the people that I have talked to in the projects want nothing to do with defunding the police. They have to live with all the shootings. They want good police, not no police.”

During last week’s CRB meeting, Mendez and Watson were elected as the board’s new chair and vice chair, respectively. Member Deirdre Gilmore was not in attendance and Carpenter abstained from voting.

Carpenter addressed the leaked text messages. “To think about the terms ‘flying monkeys,’ and identifying low-income neighborhoods as projects, going after someone’s child…you’re asking me to vote in a system that has supported this [and] has not held itself accountable as we want to hold our law enforcement accountable,” said Carpenter.

During public comment, community member Katrina Turner asked why Carpenter or Gilmore were not nominated as chair, and claimed the board needed to be dismantled. “To see you all vote, and vote the men in again, what in the world is wrong with you all?” she said.

Brown and Fracher claimed that their use of the term “flying monkeys” was not racist, but was a “professional psychological term” and referred to the blind supporters of “narcissistic” Walker.

Fracher also criticized the FOIA for compromising members’ privacy. In public comment, Conn later maintained that the FOIAed information was public business, and urged Brown and Fracher to resign.

City Councilor Michael Payne encouraged the board to focus on filling its empty positions and fixing its tarnished image. He suggested the members go on a retreat to address their internal divisions.

“If the board is not able to be successful and do these things in a professional manner, the people who are going to be sitting back and smiling [are] those who don’t want to see police oversight,” said Payne.

Privacy powers

Meanwhile, debate continues over the specific operating procedures and legal powers of the board. A state law passed last year to grant broader authority to civilian review boards around the commonwealth left certain points open to interpretation. At issue at the moment is the amount of public information that must be disseminated during the hearing process.

In a public statement last week, The People’s Coalition wrote that it was “concerned about some aspects of the ordinance” that establishes the board’s powers. “We are particularly concerned about efforts by City Council to have all hearings and evidence in secret…secret proceedings are in direct contrast to the purpose of the Board which is to provide open and transparent oversight of the police department,” reads the statement.

Mayor Lloyd Snook explained in several emails that council wanted the board to be able to make disciplinary recommendations based on confidential information, and not have to release that information to the public. The board would hold a public hearing to determine whether police misconduct occurred, but deliberate in closed session and announce its decision to the public.

The current state law does not specify whether or not a police oversight board can do anything in private. There is at least one bill, HB 631, currently in the General Assembly that would clarify these rules, said the mayor.

“There is also one (hopefully rare) case where there might be some confidential information on the question of whether police misconduct occurred—that situation would be where the allegation is of a sexual impropriety, and the complainant does not want to have their private humiliation relived in public,” wrote Snook. “We want the [board] to do all that it can out in the open, and to have access to confidential information as they make a decision that will be publicly announced.”

Local attorney Jeff Fogel pushed back against the mayor in an email, claiming that HB 631 would allow all board hearings and evidence to be heard in private. According to the bill’s proposed summary, it would permit the board to “hold a closed meeting to protect the privacy of an individual in administrative or disciplinary hearings related to allegations of wrongdoing by employees of a law-enforcement agency, where such individual is a complainant, witness, or the subject of the hearing.”

“One definition of private is secret. You have also advocated for secrecy for all evidence,” Fogel said. “There was never a public discussion about whether secrecy was appropriate and there should have been.”

The 2022 Virginia General Assembly session, which could provide clarity on this point, began last week.