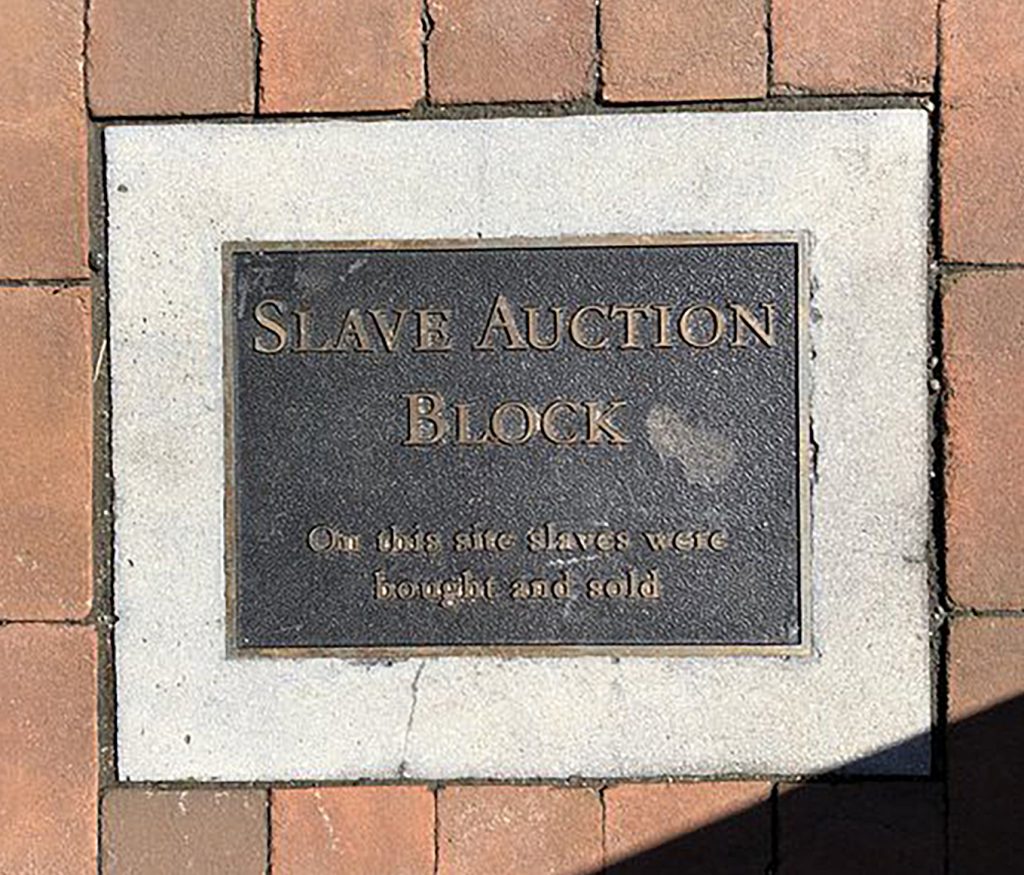

It’s been over two years since a local resident threw the Court Square slave auction marker into the James River, and Charlottesville is slowly—yet surely—moving toward erecting a new memorial. Since 2020, the city’s Historic Resources Committee has met with several dozen descendants, gathering their input on how to properly memorialize the thousands of enslaved people who were bought and sold downtown.

On Tuesday, SUNY Binghamton history professor Anne Bailey, an expert on slavery in the United States, met with local descendants before giving a talk at the Central Library on memorializing the victims of slave auctions and healing from Charlottesville’s painful history. A recording of the event is available to watch on the Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society Facebook page.

“[The descendants] are just going to meet with her and talk about commemorative events, and kind of explain what’s been going on here for the past several years in Charlottesville,” explained committee member Jalane Schmidt during an April 8 HRC meeting. “Dr. Bailey works with descendants of the Butler plantation sale [in Savannah, Georgia], and they’ve been gaining some traction with commemorative events in the last several years.”

Schmidt said she would ask participants to share notes from their meeting with Bailey, so the committee can use them to further guide descendant engagement. “It’s a balance between wanting to give them space, and also wanting that to inform the process.”

Last month, a small group of descendants also met with University of Virginia graduate students Jake Calhoun and MaDeja Leverett, who have been searching Albemarle County’s chancery records for sales of enslaved people for several months. So far, they have identified the names of over a dozen enslaved people who were sold on the courthouse steps.

Schmidt, director of UVA’s Memory Project, said during the HRC meeting that she may add another student to the research team, so they can try to get through all of the sale records by the end of this summer. However, the time-consuming project may not be completed until next year.

In February, the committee sent a progress report to City Council, detailing the descendant engagement process and requesting up to $1 million for the new memorial, which could be erected at a variety of possible locations, including Court Square, Court Square Park, adjacent to Number Nothing, or in front of the Albemarle County Courthouse—either in place of the old Monticello sign, or where the Confederate Johnny Reb statue stood. It remains unclear when council will allocate funding for the long-anticipated project.

“There is an expectation that one of the future projects is a significant physical memorial, likely in Court Square,” reads the report. “The second desire is an educational component that interprets the chattel slavery system throughout antebellum Albemarle County.”

“We do not anticipate that only one action or construction will be created, but rather a collection of projects serving unique but related purposes,” the report continues. “We anticipate that these projects will cost from $500K to $1M, [covering] locations throughout Charlottesville and Albemarle.”

During last week’s meeting, the committee also briefly discussed the draft of the downtown walking tour map, which is still being edited. Since 2020, a city subcommittee, including HRC members, has been working to revamp the antiquated map.

Member Dede Smith explained that the new map will move away from “broad themes” and highlight about 14 sites in Court Square, on Water and Market streets, in Vinegar Hill, and on the Downtown Mall. “We’re still grappling with what content to include and how to be inclusive,” said Smith.

“I know there’s been continual concern over the progress of this, but we really are trying to do something that is very different,” added chair Phil Varner. “Once we get there, it will be something that is hopefully used for a very long time, that is useful for people, and more representative of the area.”