Surrounded by towering trees and flagpoles, Charlottesville resident and Vietnam War veteran Bruce Eades walked to a podium in April 1995 at the very first Vietnam memorial in the nation and began his healing.

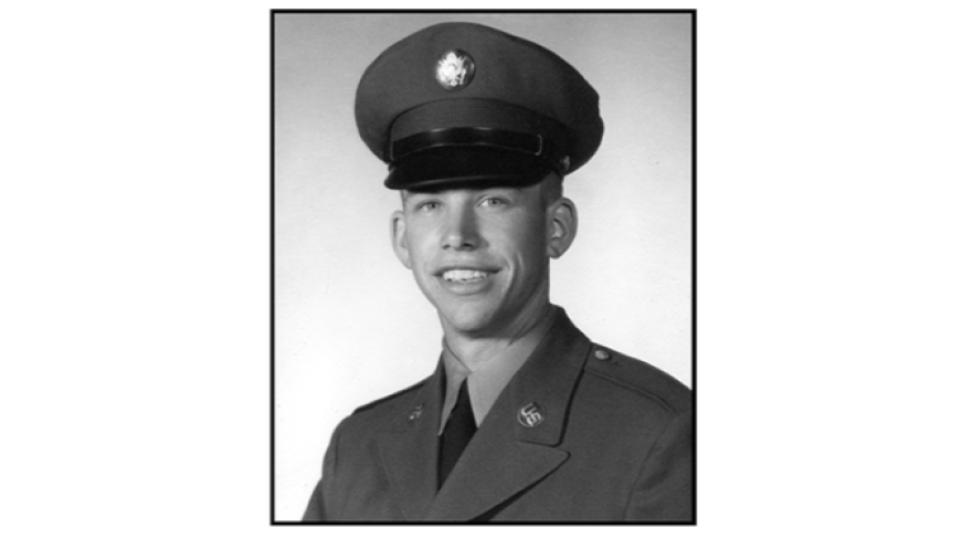

“I had to face my demons,” says Eades, who saw combat as a rifleman and interpreter in Vietnam from 1967 to 1968, but had never talked openly about it until that moment, 27 years later. He had not even shared his stories with his wife Joan and their daughters. In fact, when Eades first returned from Vietnam, he consciously chose to distance himself from his identity as a Vietnam War soldier. He grew his hair out, bought a Volkswagen van with tie-dye curtains, and moved to Miami, living like a “weekend hippie,” as he described it.

But on that April day at the Dogwood Vietnam Memorial, Eades spoke out, addressing a feeling of being slighted that he had not fully confronted until that moment.

“Because of the stigma associated with the Vietnam veteran,” Eades said to an audience of local veterans and their families, “I, like many others, rarely spoke of my experience in Vietnam and I kept those memories sealed inside me, not revealing them to anyone. I hid my tears when I remembered my fallen friends.”

Since that speech in 1995, Eades has returned often to the Dogwood Memorial. He’s mowed its grass. His wife would embarrass him and snap photos as he tended it. He would pray at the memorial, too, sometimes in the rain.

“I’d cry a lot,” Eades says, remembering his early visits to the site that helped soothe his mind and settle his soul.

Now, every April, he takes part in a ceremony of remembrance at the memorial. Since 2016, he has been president of the Dogwood Vietnam Memorial Foundation. He nicknamed the spot “the hill that heals.”

“Once I [spoke], I realized that I owed those guys a lot,” says Eades, referring to the 28 men from the Charlottesville area who were killed in Vietnam and whose stories are told with plaques at the memorial.

As America prepares in 2025 to recognize the 50th anniversary of the fall of Saigon that ended the Vietnam War, the Charlottesville-based group that maintains the country’s first Vietnam memorial is seeking support to continue its mission as a destination for individual and communal healing.

The Dogwood Foundation plans to expand the memorial with a two-part project: a brick plaza that will include 26 more Vietnam veterans’ stories and an Access Project that would make the space more accessible by adding a parking area and a pedestrian bridge.

The new parking area will fit alongside the trail that hugs the John Warner Parkway. The bridge—which will be 110-feet long and 14-feet wide—would stretch over the roadway and connect the parking area to the memorial. It would comply with guidelines set by the Americans with Disabilities Act. Currently, the memorial’s configuration makes it challenging for older veterans and residents to access. The expansion project is aiming for completion in 2026.

Born in a barbershop

On a fall day in 1965, a barber chatted with two friends at his Charlottesville shop. The conversation centered on national news that was starting to have a local impact. Eighteen-year-old Earlysville native Champ Lawson had died November 4 in a mid-air helicopter collision over South Vietnam after three months there. Lawson’s wife was pregnant with their first child. Because of the combat accident, Lawson never met his son, CJ III. Earlier that year in March, President Lyndon Johnson had ordered America’s first combat troops to Da Nang in Central Vietnam. Lawson had received his assignment in July.

So Ken Staples, owner of Staples Barber Shop, brainstormed with local real estate agent Bill Gentry and engineer Jim Shisler. Lawson’s death was central Virginia’s first casualty of the war, but surely more would come, the trio thought.

And in that moment, their idea was born: Build a memorial that showcased the spirit of sacrifice represented in residents like Lawson.

Sixty years later, this historic showcase endures. The 28 soldiers honored there represent a diverse snapshot of central Virginia life in the 1960s: young men born in the Charlottesville area, and those who arrived later because of a parent’s job or because they enrolled at the University of Virginia. The memorial is home to graduates of the all-Black Burley and Jefferson high schools, to students from the newly integrated Lane High School, and also to University of Virginia student-athletes and ROTC trainees.

Their backgrounds vary, but the men are united in their fate and their purpose: They all died in Southeast Asia while serving the U.S., their lives cut short by war. Their absences were felt by family and friends who had hoped for their return.

“What I always think,” says Peggy Wharam, Champ Lawson’s older sister, “they were so young. They really didn’t get to live their life. I thought, ‘Here we are, doing picnics and parties and having babies and building houses, and they missed it.’”

Three days after the barbershop epiphany, Staples, Gentry, and Shisler met on a grassy knoll at the southeastern edge of McIntire Park. They agreed that this spot, dangling majestically over Route 250, would be the site of the memorial.

Then Shisler made the vision a reality. In short order, he convinced Charlottesville’s city manager to approve the plan, and construction on the memorial finished in January 1966. It became the first civic/public memorial in the U.S. dedicated to soldiers from the Vietnam War, built 16 years before the national memorial in Washington was christened.

The Vietnam War ended in 1975, but the importance of the memorial was just beginning. For the next six decades, it has become a site of healing for friends and family of the 28—like Wharam—as well as for veterans like Eades who seek a way to confront their war memories and to share war stories with family and friends.

For Wharam, healing from the loss of her brother Champ has taken time.

“I took all the pictures down,” she says. “I put everything away for maybe 10 years.”

She now visits the Dogwood Memorial often, especially on Wreaths Across America Day in December, when holiday wreaths are laid at more than 4,000 memorials and grave sites nationwide and abroad.

Cause of the soldier

One summer day in 1994, Shisler saw Eades mowing the grass around the memorial and invited him to share his story. After a period of soul-searching, he agreed to deliver the speech that began his healing.

For too long, American society deprived Vietnam War veterans of an outlet for their grief, for their pain, for their bewilderment over what exactly happened in Southeast Asia. The Vietnam veteran stereotype became that of a homeless, drug-addicted man, troubled and adrift. How do you rewrite the narrative and jolt people into understanding your plight, without sounding preachy or resentful?

For Eades, he wants to change the narrative of the Vietnam soldier by sharing how veterans such as himself returned from the war to build their own businesses and contribute meaningfully to their communities. After his 13-month tour of duty, Eades used the GI Bill to earn a college degree in Miami. When he returned to Charlottesville, he bought a crane and started a steel company, studying construction management at Piedmont Virginia Community College as he expanded the business. His career in welding spanned 25 years and two companies, building churches, firehouses, and shopping centers.

Eades has dedicated himself fully to the cause of the soldier, volunteering for many veterans’ support groups. He has also examined his mind and soul for what he and his country did in Vietnam, and he’s reached some conclusions about the conflict in Southeast Asia and about war in general.

“Even a good day in Vietnam was pretty sickening,” Eades says. “War is ugly, and if I don’t get any other point across, I think that people in our country need to know that war is not a good solution. You think it’s going to be short, but it never turns out that way. People take war too lightly. The saving grace for this country right now is our veterans, because our veterans understand that. Nobody hates war more than a warrior.”

Eades also offered guidance on how to meaningfully support veterans, aside from the requisite “thank you” at a barbecue or at the grocery store.

“We thank the veterans, but we don’t ask them questions about how it was being away from their families,” he says. “The conversation ends often with, ‘Thank you.’ That should be where the conversation starts. You learn a lot more listening than you do talking.”

Eades’ wife Joan has done much listening, whether it’s when dishing food to veterans at American Legion meetings or during rides on the back of her husband’s motorcycle in the Dogwood Festival parade. She lived a block away from him growing up, on Forest Hills Avenue in the Fifeville neighborhood. He would often see her playing at Forest Hills Park. Fast forward to Eades’ return from Vietnam when he moved back in with his parents, and was soon pricked by cupid’s arrow.

As Eades tells it, on their first date, he escorted Joan on one of his motorcycles. Joan was so scared by the experience that she refused to go out with him for the next three months. Eventually, the courtship commenced, and they danced at a local club called The Second Sizzle.

“She sizzled a lot, so I married her,” Eades says. “She changed my life. She gave me a reason to want to be a better person and to start caring again. When I came back, I knew I needed a balanced life. I knew I needed a relationship.”

Like her husband, Joan sees the need to continue to find ways to make Vietnam veterans feel welcome and appreciated in American life. In 2018, Charlottesville’s Dogwood Festival parade invited local Vietnam War veterans to march as honorary grand marshals. On that April day, Joan spoke to the honor’s symbolism. After all, Vietnam soldiers didn’t receive the same victory celebration that their fathers enjoyed after World War II. America didn’t “win” the Vietnam War like it decisively “won” the Second World War, if war stories should even be told using the frame of victories and defeats.

“It is very important to have a welcome-home parade,” Joan says. “These men finally feel like they did something honorable for their country, and they’re just a very special breed of people who love their country, fought for their country, and they did what was asked of them.”

As the Eadeses continue to encourage individual and collective healing, Wharam’s mind turns to remembrance. Who will tell the stories?

“[Champ] told me one time, ‘I just want to do something to be remembered by,’” she says. “I just realize that in a couple generations, no one is going to know who he was.”

So long as the keeper of the stories— the Dogwood Vietnam Memorial—stands, the story of Lawson’s contribution, and many others like it, will endure.

A planned expansion

The Dogwood Vietnam Memorial Foundation is currently planning a Brick Plaza Project to honor any veteran who served in the U.S. military at any time, in any place, and in any conflict. The funds from the project will go toward the memorial’s expansion costs.

To support the Brick Plaza Project, veterans and their families can buy a brick and inscribe messages that honor service and sacrifice, in keeping with the spirit that Staples, Gentry, and Shisler originally hoped to capture. The bricks will be featured on a new plaza that is part of the expansion and will include 26 additional biographical plaques honoring University of Virginia students who fought in Vietnam.

The Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society will host a free discussion at 6pm November 14 at The Center at Belvedere to address the question, how does a community heal from war, especially one as divisive as the Vietnam War? Eades and other Dogwood Vietnam Memorial leaders will share their thoughts and continue their mission as local healers.

For more information on the Dogwood Vietnam Memorial and its expansion project, go to dogwoodvietnammemorial.org.