Since the 1940s, documentary photographer and filmmaker Gordon Parks has remained relevant as both a visual chronicler of injustice and an example to aspiring artists everywhere. “He could turn an ordinary life into something extraordinary,” says John Maggio, the director of A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks, which takes its name from Parks’ memoir.

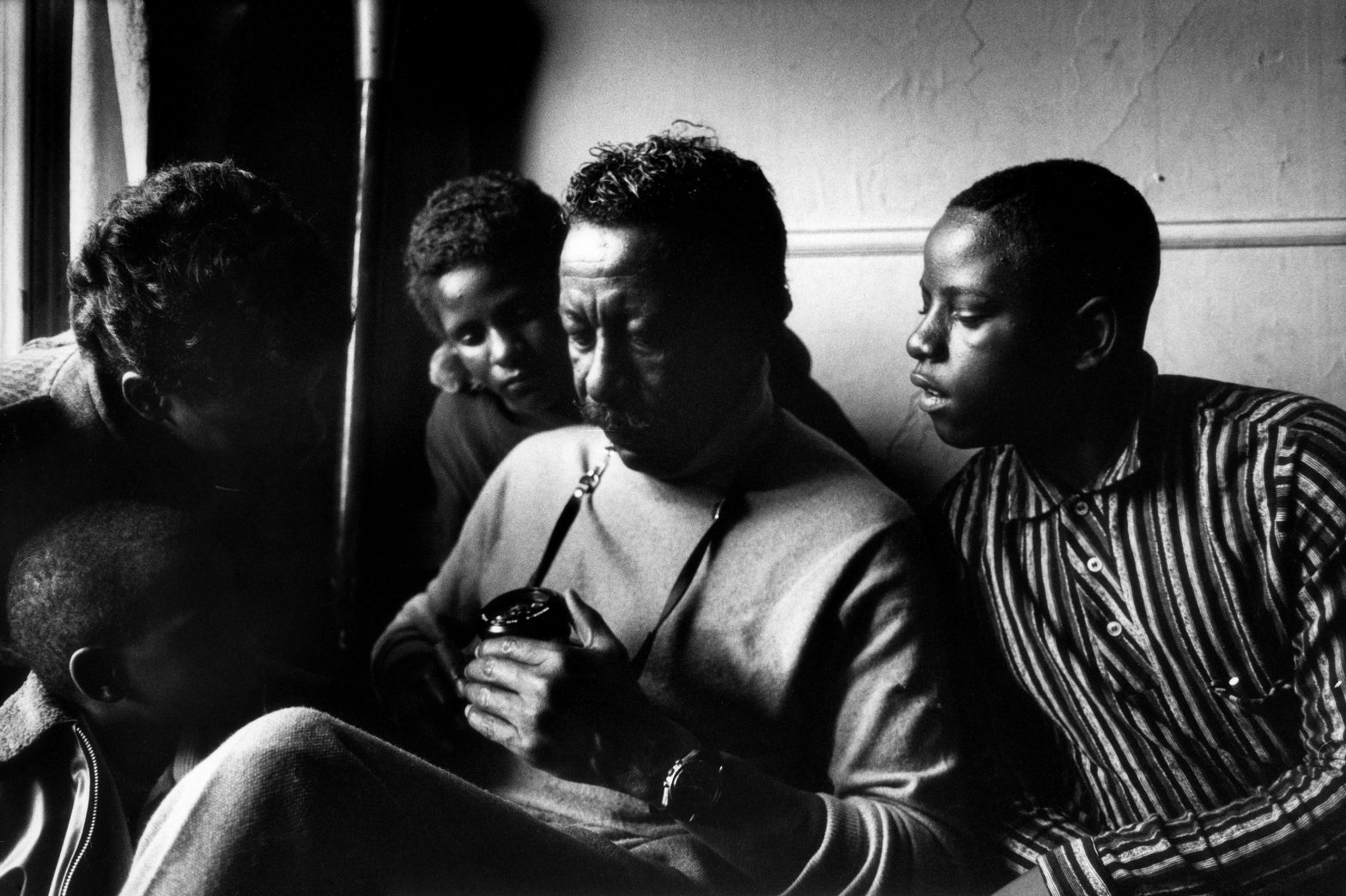

Among Parks’ famous works is his 1967-68 Life magazine photo documentation of the Fontenelle family’s struggles in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. “Not to diminish the importance of covering the Fontenelle family in a run-down tenement, but he also got the beauty of the composition,” Maggio says.

“Parks is the perfect amalgam of both artist and journalist,” says Maggio, showing a photograph of a woman sitting with some of her children, pleading silently with a poverty bureau worker. “That makes him great. Look at the mother’s eyes—so grave.”

Born into poverty himself, Parks saw power in photography and taught himself how to operate a camera. He worked his way onto the masthead of Life magazine, and was the first African American to shoot for Vogue, as well as the first Black director of a major Hollywood studio movie, Shaft. He also was a noted writer and composed music for films.

In addition to discussing Parks, Maggio’s documentary showcases the trajectories of three newer artists who wield cameras to tell stories. “I didn’t want to keep Gordon encased in amber. I wanted to see his legacy in play today,” says Maggio.

He calls Baltimore’s Devon Allen the nearest extension of Parks. Finding a camera pulled Allen away from a perilous place to the cover of Time magazine. Other artists influenced by Parks and featured in the film are LaToya Ruby Frazier and Jamel Shabazz, who create affirmation in their work, Maggio says.

As a young man hanging around his painter-sculptor father’s studio, Maggio “absconded with a Time-Life photo compendium” that captivated him as he studied Parks and the photos that elicited strong emotions. Today, he says he admires Parks’ bright and colorful series shot in the South. Full of life and joy, the photos defy the harsher stereotypes of the region.

Maggio, who was once a journalist, won an Emmy for “The Untold Story of the 2008 Financial Crisis.” He says now is a golden age for documentaries because of the resources that streaming platforms provide for stories that tell us about our society and world.

Maggio cites the Unite the Right rally as an inspiration for his work on A Choice of Weapons. “There was an eerie intimacy to the tiki-torch march, and it felt like something out of a Nazi propaganda film. It was chilling,” he says, before expressing gratitude for the filmmakers and journalists on the scene at the time. The two days of violence in Charlottesville were part of a pattern that includes the deaths of Sandra Blanton, George Floyd, and others. “The sad part of this is that it’s a conversation we continue to have,” he says, adding that there is still a need for potent imagery, as young artists evolve. “It is their story to tell, the important narrative work that can effect change.”

A Choice of Weapons: Inspired by Gordon Parks

October 28

Culbreth Theatre