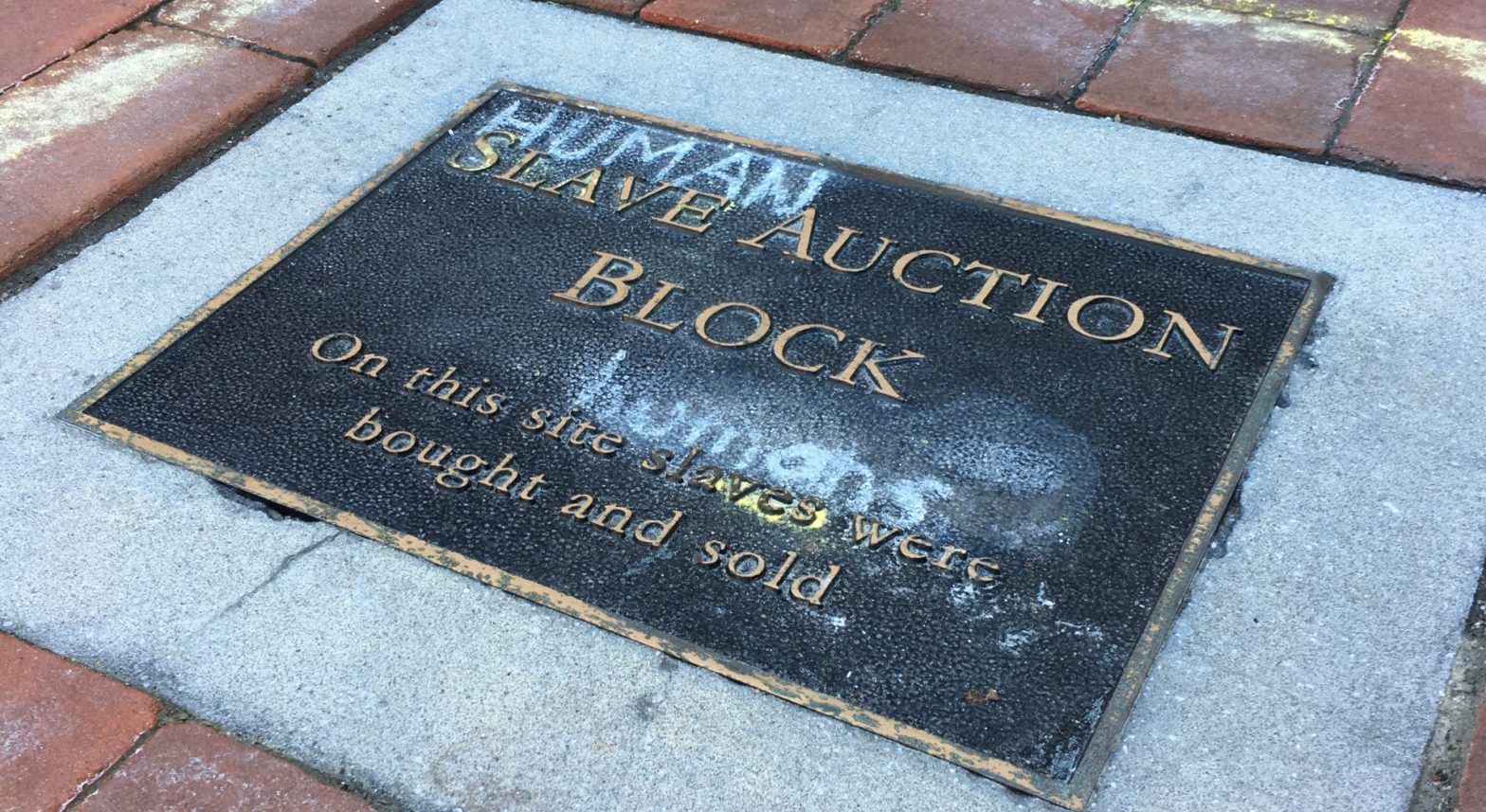

Charlottesville’s most famous monument made national headlines last week, when City Council voted to hand the statue of Robert E. Lee over to the Jefferson School African American History Center, which will melt it down and reshape the metal into a new piece of art. Across the street, meanwhile, a less conspicuous but no less important public history project is underway in Court Square.

This spring, Charlottesville’s Historic Resources Committee met virtually with more than a dozen descendants of enslaved laborers, gathering their input on how to properly memorialize the thousands of people who were bought and sold in Court Square. The committee paused the meetings over the summer, however, while it worked to secure funding from the city for the complex memorial project.

During the committee’s December 10 meeting, chair Phil Varner explained that the new Court Square memorial, as well as potential additional historical markers in Charlottesville and Albemarle County, could cost as much as $1 million. He suggested the city allocate funding from its long-term Capital Improvement Plan, and form a partnership with Albemarle County for the costly project. The committee currently has around $35,000 in its budget.

Councilor Heather Hill noted that the city has other costly projects coming up, including a major school reconfiguration. “There’s just a lot of things that we haven’t done that we have been pretty conservative about through the pandemic, so we don’t just have a bunch of money laying around,” she said.

“The only immediate thing that I have in mind is getting something in the CIP to start, so that over a number of years, we will continually put money towards something we will eventually converge on,” Varner said.

Hill—whose term on City Council concludes at the end of the year—encouraged the committee to present a report to council about the status and timeline of the engagement process, as well as a funding request for the entire project, at its January 18 work session.

During public comment, local resident Richard Allan—who stole the original slave auction block marker and threw it into a river last year, frustrated with the city for not erecting a better memorial—asked if the city would consider relocating the two parking spaces in Court Square Plaza that obstruct public view of the auction block site. Allan’s Court Square Slave Block Citizen Advocacy Group had an engineer inspect the area, and learned that the parking spaces could be moved across the street, he explained.

Varner emphasized that the committee has not yet started to design the memorial. “We’re gathering information, we’re building community,” said Varner, “to inform a future process.”

The committee also discussed resuming its community engagement by inviting historian Anne Bailey, an expert on slavery in the United States, to speak about slave auctions in February or March.

“One of the most poignant remarks we heard at some of the engagement meetings…was that descendants came and just didn’t know anything about the site or its history,” said city planner Robert Watkins. “Any educational or informational event is really getting people involved and making sure that they have a say in this project.”

Varner agreed to bring an interim report to council by February.

“For five years basically, we’ve just been fighting and struggling in just lots of different ways,” added member Jalane Schmidt. “It feels like now…we’re kind of in a new space where we feel like we can move forward.”