As a writer and theorist, Jennifer C. Nash’s work is deeply connected to political and emotional realities of Black feminism, inviting readers to probe the space between theory and embodiment. She is the Jean Fox O’Barr Professor of Gender, Sexuality, and Feminist Studies at Duke University and the author of four books. Nash spoke to us about her latest, How We Write Now: Living With Black Feminist Theory.

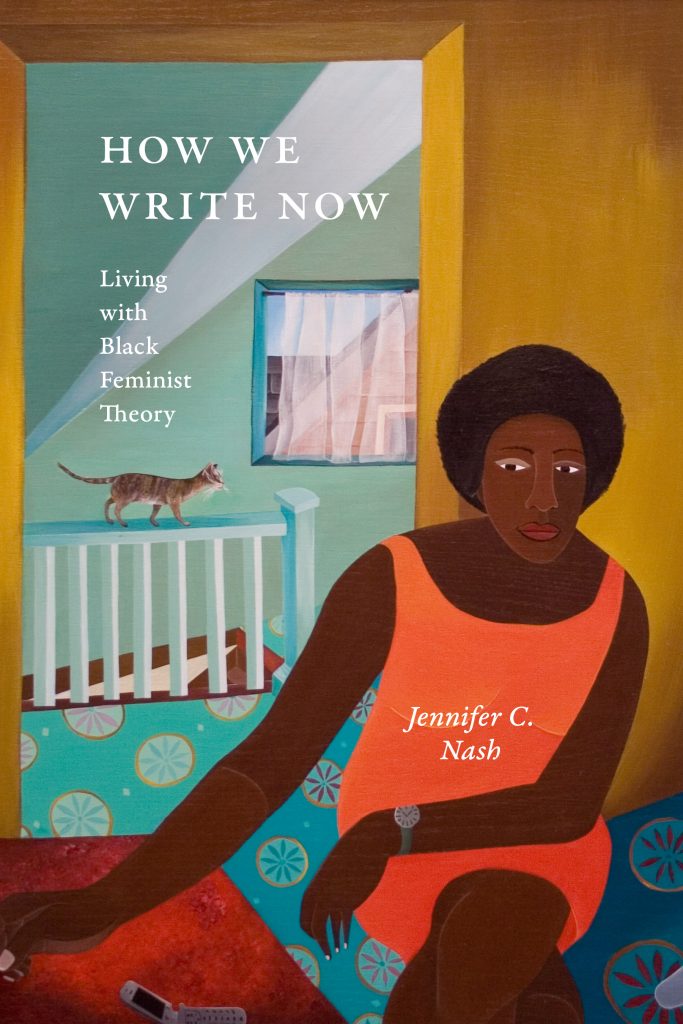

Publicity photo.

C-VILLE Weekly: In your new book, you focus attention on Black loss in the age of Black Lives Matter, working to “disrupt prevailing conceptions of loss” by exploring slow loss through the work of Black feminist writers as well as your mother’s Alzheimer’s disease. As a Black woman who has spent your academic career immersed in Black feminist theory, did writing this lead to any disruptions or experimentation within your work?

JCN: If in my earlier book I was trying to think about how often we saw politicians (especially on the left) reference a Black maternal health “crisis,” and how often we saw them turn to Black mothers as symbols of grief and pain, my new work wants to think about how the voice of contemporary Black feminist theory, one that is preoccupied with loss, is always thinking about loss through maternal figures. Sometimes this is about mother metaphors—the loss of motherlands, mother tongues—and sometimes it’s about mothers and foremothers.

In many ways, [this] project was born out of the subtitle: Living with Black Feminist Theory. I have lived with Black feminist theory for the entirety of my academic career, returning to books and articles not just as sources or evidence, but as resources and tools for living. That’s why I wanted How We Write Now to try on—or inhabit—the voice I argue has come to be so central to contemporary Black feminist writing.

For me, the personal voice, the beautiful voice, that I take on in the book is one that moves me toward grief rather than treating grief as something to escape, to recover from, to get over. It is a voice that emphasizes that doing justice to loss requires offering it companionship, staying with it. It is a voice that insists that there’s no such thing as being “too close” to what we study, especially when it comes to loss. In a moment where so much writing on loss is about moving on, getting beyond, transcending, I am drawn to the ethics of a project that insists that we sit with loss, stay with it.

There is a tenderness and intimacy in this book that’s different from your past work. How did you conceptualize the risks of undertaking this?

It is definitely the case that writing about the people you are closest to is a risky endeavor, particularly when the writing discloses that which they might refuse. My mother, for example, would certainly contest her Alzheimer’s diagnosis, even as she has now lost many of the words she could have mobilized earlier to refuse the label of “dementia.” But it is also the case that my father finds a certain kind of freedom in seeing our story represented on the page. It has allowed him a way of talking to his friends about something that feels unbearable to name.

I also know that the risk of not speaking is far greater—it felt important to me, urgent even, to document this moment, both the moment where Black feminists are collectively developing a voice to name loss, and the moment in which my mother becomes more unfamiliar to me, and the world becomes more unfamiliar to her. As I note in the book, I think the ethical grappling with the risks of disclosure, with what it means to tell stories that implicate the people you hold dearest, is actually very much at the heart of the Black feminist project I am interested in.

How did you work to avoid systems

that “peddle in Black grief” as you wrote this book?

I think the grief markets that have sprung up around Black grief have multiplied in the Black Lives Matter era. Samaria Rice—Tamir Rice’s mother—warned us about the costs of “hustling Black death.” Indeed, a lot of folks have profited from Black death—bestsellers have been born, talking heads have made careers. And I say that not to be cynical—Black death needs to be named and discussed and diagnosed. But we also have to recognize that there are new markets around that very death.

I wrote a book that I argue is about Black loss that has none of the characteristics of the Black loss stories that proliferate in the present. This is not a book about a Black boy or man being murdered by the police, nor is it about the anticipated loss of my Black (male) child. It is not a book about the forms of violence that are regularized and anticipated, the state-sanctioned theft of Black children that ends with non-indictments and non-convictions. I am trying to lay claim to the frame of Black loss to think—not about the spectacular and expected death of Black children—but about the slow, endured, and quiet deterioration my mother experiences. I want to think about what it might mean to develop a frame of Black loss that can make room for her and the deterioration of her brain. In that sense, I think the story I want to tell is necessarily outside of the grief economies that I want to name and problematize.