A professor of printmaking at UVA, where he has taught since 1985, Dean Dass began painting 20 years ago, with the process-rich, methodical approach of a printmaker. “Dean Dass: Venus and the Moon” at Les Yeux du Monde marks the artist’s 10th solo show at the gallery, and he continues to work in both disciplines.

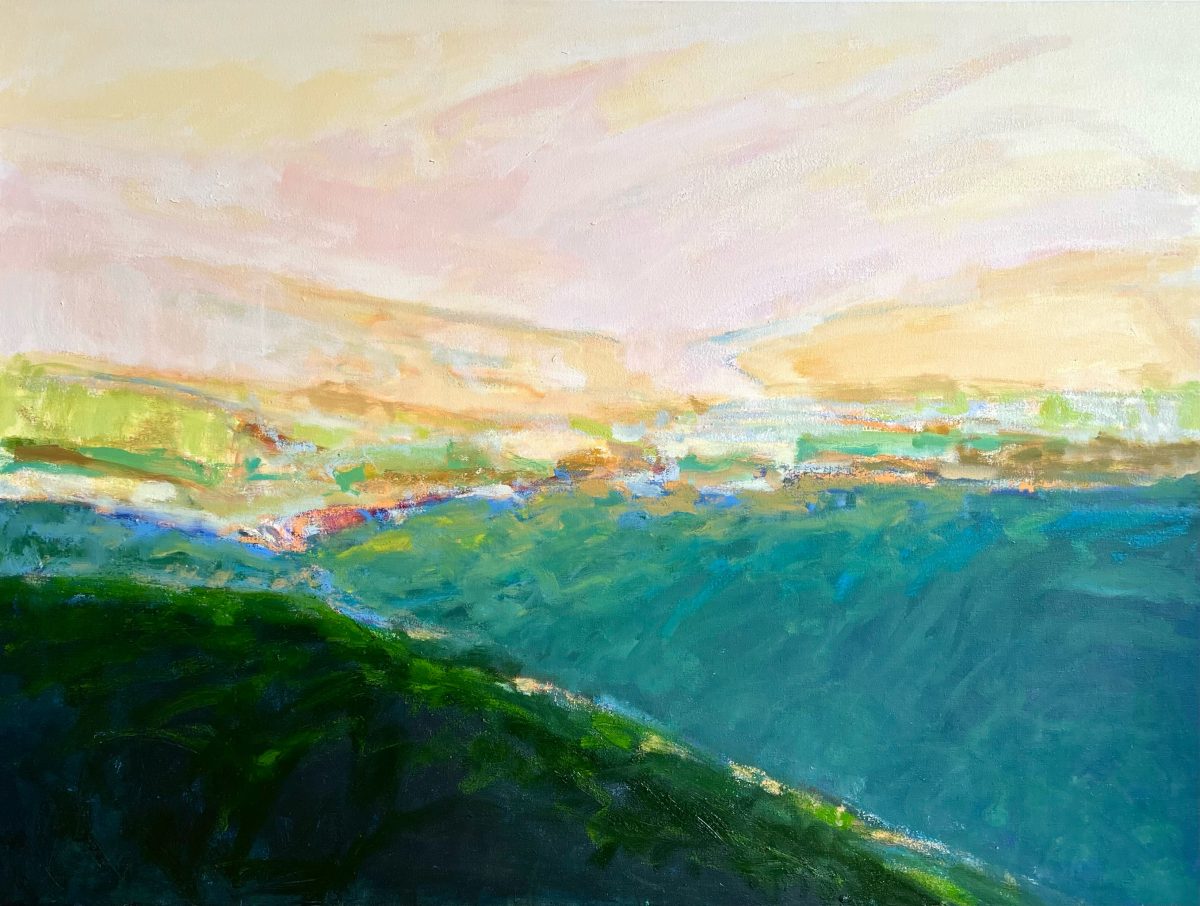

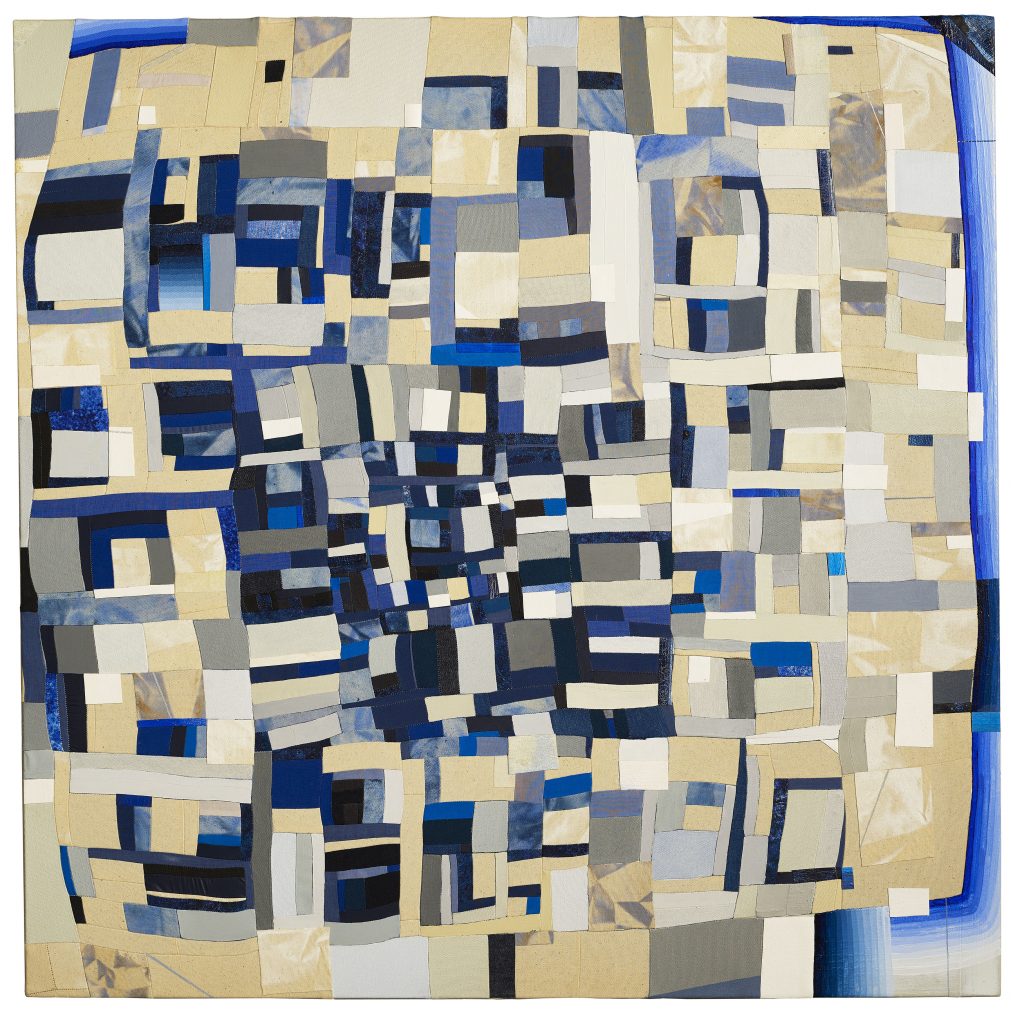

Looking at the show, two styles of work are immediately apparent. There are the evocative paintings that capture so perfectly the effects of light and atmosphere on the landscape. And then there are the more stylized works that feature abstract shapes and heavily worked surfaces.

Dass produced the landscapes following a trip through northern Michigan and Ontario that paralleled one taken by The Group of Seven, a cohort of Canadian landscape painters, active between 1920 and 1933. Like Dass, the Seven shared an affinity for the rugged beauty of the north as well as an appreciation of the work of Nordic artists like Edvard Munch, Jonas Heiska, and Akseli Gallen-Kallela.

“Fireflies,” “Figure in Space,” “Seven Clouds,” and “Flower,” are representative of the other strain, revisiting images Dass initially used in collages and prints produced 25 years ago that were first exhibited in a 2001 show he did at Galleria Harmonia in Jyväskylä, Finland entitled “Räjähdyksiä Maisemassa” (“Landscape with Explosions”). The works were inspired by screen shots of the video games his children were playing at the time, as well as sci-fi film stills. You never know when inspiration will strike and these small, seemingly insignificant and rather eccentric images have provided a wealth of fodder for Dass over the years.

Dass takes a profoundly cerebral approach to his practice, incorporating history, mythology, and philosophy into the work. This may help explain why he sees his entire output as closely aligned. It’s true, even his most abstract works are rooted in nature—the titles: “Clouds,” “Fireflies,” “Flower,” and “Explosions” tell you this. And he goes further, incorporating nature directly into the works, using such organic materials as graphite, gold leaf, and mica. Even the washes of pigment that pervade the work have a connection, recalling the “impossibly pink” rock formations Dass encountered in Canada.

Working with intention, but also leaving a good deal up to chance, Dass embraces both new and old media and techniques. He uses the same glazes that northern Renaissance artists employed and mixes his own pigments at the same time that he takes inspiration from computer and TV screen images, while availing himself of an inkjet printer.

Working with intention, but also leaving a good deal up to chance, Dass embraces both new and old media and techniques. He uses the same glazes that northern Renaissance artists employed and mixes his own pigments at the same time that he takes inspiration from computer and TV screen images, while availing himself of an inkjet printer.

With its heavily worked, almost excavated quality and dynamic abstract form, “Figure in Space” seems both ancient and contemporary, flat and three-dimensional. Rendered in gold leaf, the figure of the title, with its knobby, splayed “arms,” has a kinetic quality and it seems to be floating or spinning. Its scale is unclear, it could be molecular, or some giant extraterrestrial body.

Displayed in the back room of the gallery are a series of small, mixed-media works on paper, most of which incorporate printmaking techniques. These charming, often amusing, odd pieces are appealing both aesthetically and on account of the quirkiness of their subject matter. Particular favorites are “Astronaut,” produced in collaboration with Jyrki Markkanen, the memento mori, “The King!” from 1995, “Four Tents,” and “Camping in the Clouds.”

Dass’ paintings of downy woodpeckers are remarkably evocative. There’s no bird body there, just an arrangements of brushstrokes and pigments. They’re like deconstructed birds, but they deftly emulate the soft feathers, distinct markings, and essential birdiness of their subjects.

“Etna Highlands” and the smaller, looser “Frozen Bog Etna Highlands” present the same scene of woods and water in winter. The paintings are modest in terms of subject matter and palette, and yet, they ring true thanks to the way Dass creates the light of the setting sun. And it’s not just that the apricot hue is spot on, but the way Dass replicates sunlight filtering through the woods—its soft intangibility, the way the air can make it seem blurred, and the spots of brightness near the horizon that occur under certain atmospheric conditions.

“Birch Near Superior” displays a similar combination of modesty and virtuosity. Here, Dass uses precise daubs of paint in the foreground, giving over to elongated blurs in the background, to capture the visual effect of wind through leaves. The overall palette is quite somber, but even with very little, Dass conveys the sparkling quality of the day with dots of yellow pigment on the birch leaves, a couple of white reflections, and a small patch of blue sky.

In the glorious “Bog Near Sault Ste. Marie,” we see both the technique—the brushstrokes, rubbed areas, and squiggles that are brilliant stand-alone passages of pure abstract painting—and also the illusion, the movement of the trees and the sunlight dancing on water that they evoke.

Dass’ images of pristine nature are deeply moving. We appreciate their beauty, but we also recognize how very fragile they are, especially today when so much is under assault. And this gets at a fundamental objective for Dass, namely, a two-pronged reaction to the work, where there is always something implied beyond the explicit.

There is the beauty of the image, but then something more primal, more weighty, and possibly quite melancholy creeps in. German philosopher Theodor Adorno, whom Dass greatly admires, refers to this as a “shudder.” It catches you off guard and engenders a deepened appreciation of what you are looking at. In Dass’ work, the shudder Adorno refers to may take different forms, but it is always there.

Dean Dass brings a variety of influences to his show “Venus and the Moon” at Les Yeux du Monde gallery through December 29.