Descendants will have equal say at Montpelier

The Montpelier Foundation voted last week to share governance of the historic property with the Montpelier Descendants Committee, an organization comprised of descendants of the enslaved laborers who once lived and worked on the plantation.

Montpelier is widely known as the estate of James Madison, the fourth U.S. president, but the Orange County property was also home to more than 300 enslaved laborers. In recent years, the organization has sought to bring their history to the fore. The move to formally share control of the property with the descendants community is “unprecedented,” says the foundation.

James French, the chair of the Descendants Committee, praised the decision in a statement. “This vote to grant equal co-stewardship authority to the Descendants of those who were enslaved is groundbreaking,” said French, who’s a financial technology entrepreneur by day. “The decision moves the perspectives of the Descendants of the enslaved from the periphery to the center, and offers an important, innovative step for Montpelier to share broader, richer and more truthful interpretations of history with wider audiences.”

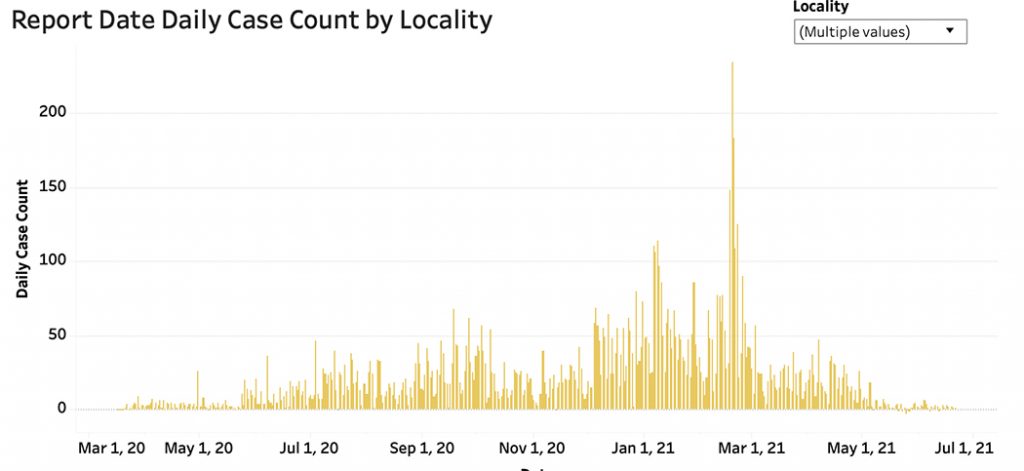

COVID cases remain steady—and low—in the Charlottesville area

From June 7 to June 21, Charlottesville and Albemarle combined reported 20 new cases of coronavirus. That’s the smallest number of new cases in a two-week stretch since the early days of the virus in the spring of 2020. The Blue Ridge Health District, which includes Charlottesville, Albemarle, and four neighboring counties, reported just two new cases on Monday and two new cases over the weekend.

Sixty-eight percent of Albemarle adults and 57 percent of Charlottesville adults are fully vaccinated. Statewide, 60 percent of adults have had both shots.

I hate losing at pretty much anything. My girlfriend hates playing Mario Kart with me due to this fact.

UVA closer Stephen Schoch, discussing his competitive mentality ahead of the baseball team’s College World Series appearance this week

In brief:

Masks won’t be prosecuted

Virginia state law says it’s illegal to wear a mask in order to conceal your identity. For obvious reasons, that law was put on hold during the pandemic, but it’ll go back into effect on June 30, when the state government’s COVID-inspired state of emergency ends. Locally, however, people who plan to continue masking shouldn’t worry—the Charlottesville and Albemarle Commonwealth’s Attorney’s offices released a joint statement this week saying, “Those who wish to continue to wear masks in public to mitigate the risks of COVID-19 spread and exposure may do so without fear of prosecution.”

Affordable Albemarle

The Albemarle Planning Commission voted 6-1 in favor of a proposed development that will see 190 affordable units, and 332 total units, constructed near the Forest Lakes community off Route 29, reports The Daily Progress. Since the proposal’s debut in March, some Forest Lakes residents have voiced their opposition to the construction, but the planning commission cited the high cost of living in the county as a key reason for allowing the project to move ahead.

Sue me? Will do, said hospitals

A study from Johns Hopkins University highlights just how aggressive UVA and VCU hospitals were in suing patients for unpaid medical bills, reports the Virginia Mercury. Both facilities stopped suing patients in 2020 after facing public pressure over the practice, but the study reports that the two hospitals were the most litigious of 100 hospitals analyzed. From 2018 to 2020, VCU initiated legal action 17,806 times. UVA finished second at 7,107.