As a youth, George Floyd dreamed of being a Supreme Court justice, a professional athlete, a rap star.

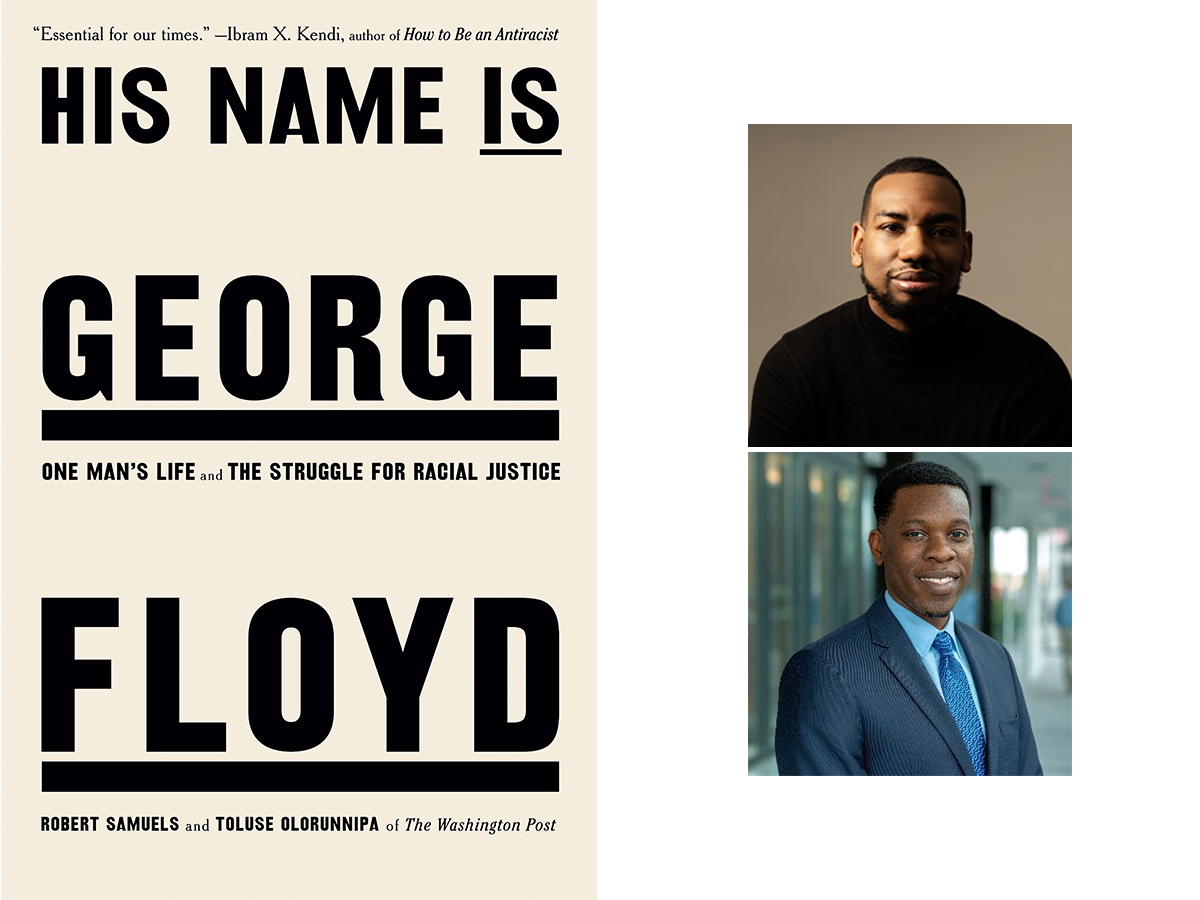

Washington Post reporters Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa document those dreams and the impact of systemic racism on Floyd’s life in their book, His Name is George Floyd: One Man’s Life and the Struggle for Racial Justice. They’ll be in Charlottesville to talk about it at this year’s Virginia Festival of the Book.

The book came out of an October 2020 six-part series in the Post. The picture of Floyd that emerged from the series and Samuels and Olorunnipa’s year of reporting “is that of a man facing extraordinary struggles with hope and optimism, a man who managed to do in death what he so desperately wanted to achieve in life: change the world,” they write.

Much of Floyd’s experience as a Black man in America resonates with Samuels. “The biggest example was the idea that if he encountered a stranger, people would often assume the worst,” says Samuels. “I think that feeling is something that resonates with lots of Black people, particularly Black men.” They exist in a world of constant fear that they might be killed, “more specifically by a police officer,” he says.

And the biggest difference between Floyd and Samuels’ experiences as Black men? “I did not encounter [former Minneapolis police officer] Derek Chauvin on May 25th,” says Samuels.

The writers found surprises in learning about Floyd’s life and getting inside his head when he wasn’t there to be interviewed. He left letters, poems, and raps he’d written. “Obviously he was a creative guy,” says Samuels. Floyd wondered why his life was not better and often blamed himself. “I don’t think people would assume he was so reflective.”

Another surprise was learning Floyd was reading and writing at grade level in the third grade, when he aspired to sit on the U.S. Supreme Court after a lesson on Thurgood Marshall. Educators say third-grade reading levels define how far one goes academically. “That really begs the question,” says Samuels, “‘What happened?’”

The authors were amazed to learn that Floyd’s great-great-grandfather, Hillery Thomas Stewart, born enslaved, was one of the wealthiest Black landowners in the South by 1870, and owned 500 acres in Harnett County, North Carolina—until Jim Crow-era white businessmen and officials stripped the illiterate Stewart of his holdings through complex, fraudulent financial instruments and tax auctions.

The family lost its land in a single generation, says Samuels. Research proved the story “a lot more terrifying than what the family said.”

With the January 7 police beating of Tyre Nichols in Memphis, many wonder whether anything has changed since Chauvin put his knee on Floyd’s neck. Samuels sees a lot of changes stemming from the widest protest movement in the history of this country.

“At least 16 states have banned no-knock raids or chokeholds as a direct line to the movement we saw with George Floyd’s death,” he says. Greater, immediate accountability occurred in Nichols’ death, with the five accused police officers fired even before the videos were released publicly, he adds.

Other changes aren’t so great—or are nonexistent. Federal police reform fizzled on Capitol Hill. When Samuels and Olorunnipa started writing, the books on racism that people said everyone should read are now ones people say should be banned, notes Samuels.

And in 2020, it seemed many were ready to have robust discussions about the fuller truths of this country’s history and its relationship with systemic racism. Now, “those are really uncomfortable questions for a host of people,” says Samuels. “You can see that with what is going on in Florida. I think there’s a real heightened challenge in this country on how we should handle and present our history and what we should learn from these moments.”

Robert Samuels and Toluse Olorunnipa will appear at the National Book Foundation Presents: An Afternoon with the National Book Awards at the Jefferson School African American Heritage Center on Saturday, March 25.