By Matt Dhillon

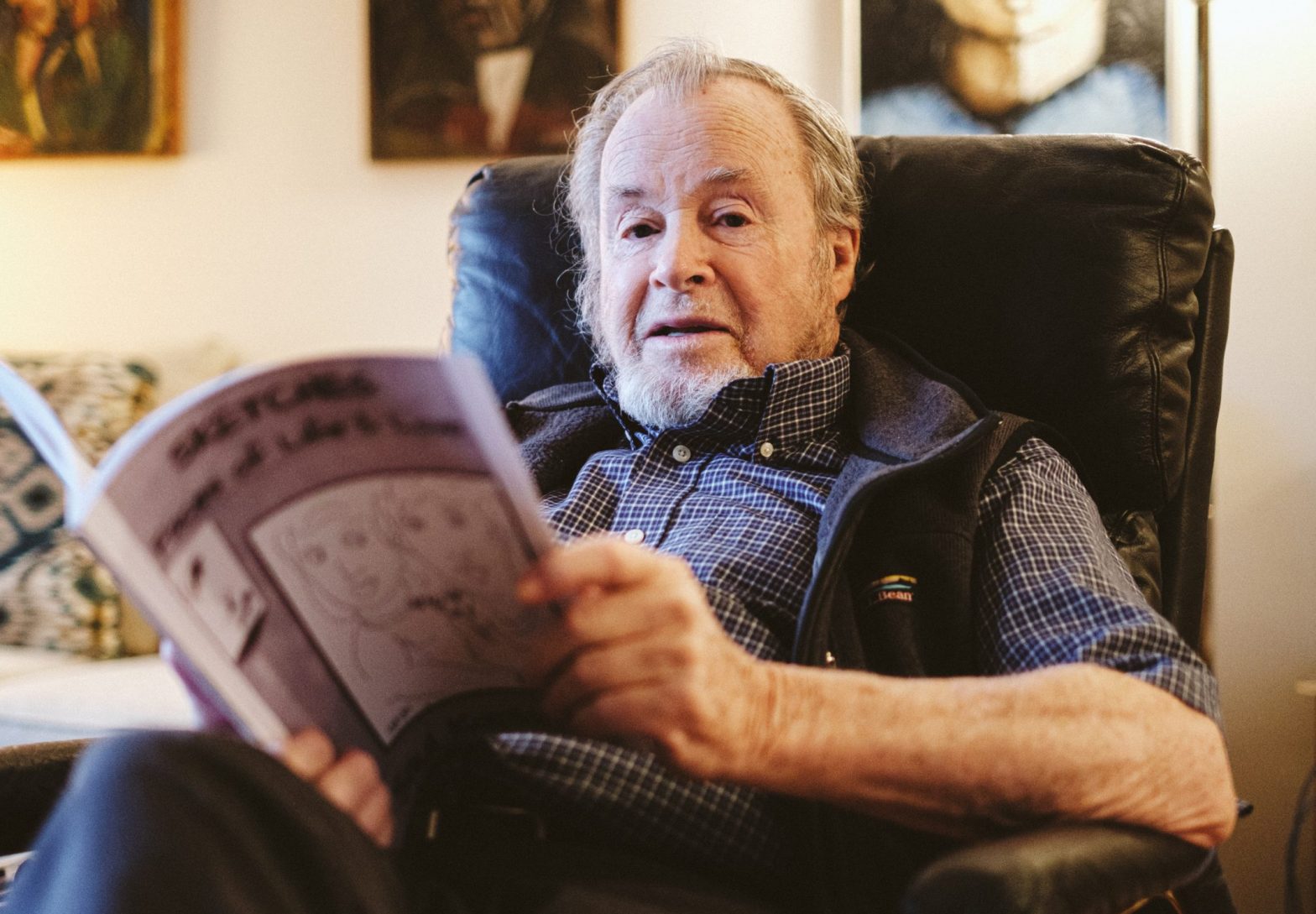

In February, Saul Kaplan marked both his 93rd birthday and the release of a new book of artwork. The self-published Sketches: Faces of Life & Love highlights what is perhaps the artist’s most discreet and most intimate medium, his drawings.

Having retired to an apartment in Martha Jefferson House, the ceramics and painting that were the priority of Kaplan’s artistic career became more difficult. But Kaplan cannot sit down with a pen without coming away with a drawing. It’s a habit he’s developed from over 60 years of practicing.

“Drawing is a muscle memory, eye muscle coordination,” Kaplan says. The memory that keeps returning to the muscles of his fingers, wrist, and arm is the memory of human faces.

Over the years, Kaplan has drawn thousands of human faces, and on every page his book is populated with that most familiar of images.

“The human face expresses everything,” he says.

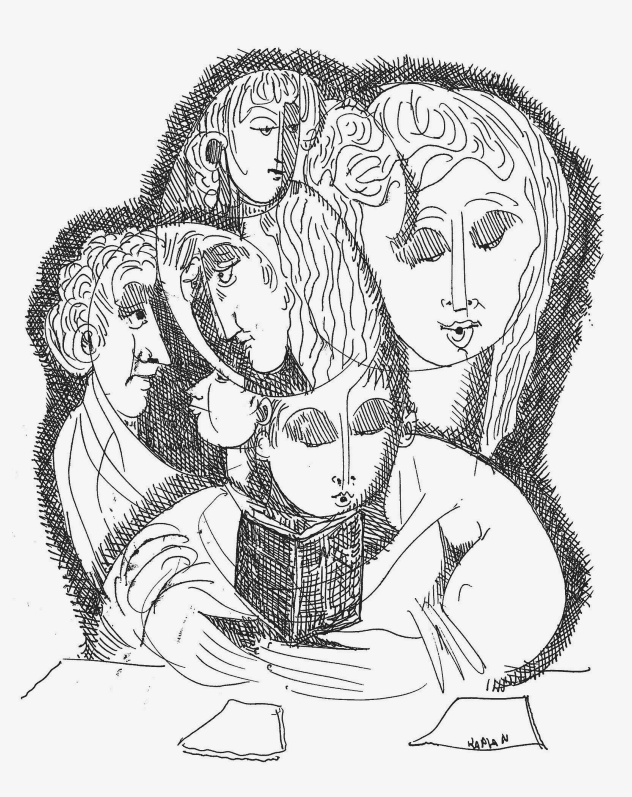

Kaplan’s simple lines craft expressions on the shifting array of faces, digging for the bare-bones of emotion buried there. We see eyes meet, or downcast, or slitted, eyes tired, or gentle, or cunning. Lips are curled, puckered, pouting, or tense. Noses sharp and soft, cheeks broad and narrow.

Perhaps it is this simplicity of bare lines that makes drawing, as Kaplan says in the book’s prologue, “the most intimate and direct form of visual communication.” While intricacy serves to expand and amplify, the simplicity of the line drawings in Faces of Life & Love go in the opposite direction, seeking to distill the essence of an eyebrow, or a lip, and identify the essential lines that carry emotion. In the most minimalist renderings, Kaplan refines a somber face into just a handful of lines.

Kaplan also alludes to ancient Egyptian drawings. “The style of the Egyptian eye has been repeated over history,” he writes. “The eye I draw, like Picasso did, had its beginning in Egypt.”

That eye—drawn over and over for centuries—mirrors Kaplan’s endless creation of faces throughout the years. In this obsessive repetition and focus on the geometry of shape, Kaplan’s drawings search for something basic about the human face, its composition, and its familiarity. As the Egyptians did, Kaplan attempts to use the very specific and precise lines of a face to strike a resounding chord.

In this collection, we see the warm human population that Kaplan has created as a result of that repetition. Most of them are not alone, drawings occupied by two or more figures in some form of relationship to each other. Often, their bodies overlap or blend so that we see two faces that share one eye, or three heads that share one torso. In these fusions there is a sense of togetherness, of something shared that merges the characters in a visceral way.

Each drawing, he says, is a kind of personal signature. “[As artists] we are making our mark some way or another. It’s a kind of waving and saying, ‘I’m here.’”

Kaplan, like his characters, tries to merge with something bigger than himself, participating in the collective story. “That’s what an artist really does,” Kaplan says. “He tries to use the medium he’s in to express something—it could be anything—but it is now part of history, a part of mankind.”

In the same way that the thousands of Egyptian eyes are actually one eye, iterations of the same form, Kaplan’s endless faces resolve into one face, waving at the world.