From redlining to racial covenants, Charlottesville’s long history of racism and segregation has created the affordable housing crisis the city now faces. Over the years, the city’s largest employer, the University of Virginia, has contributed to the problem. As UVA continues to grow and expand, more and more students have signed leases at apartments and houses around the university, leaving less and less affordable housing available for the city’s low-income residents.

In 2020, UVA President Jim Ryan announced that the school would take proactive measures to address the situation. Over the next decade, UVA plans to support the development of 1,000 to 1,500 units of affordable housing in Charlottesville and Albemarle County. UVA and the UVA Foundation will retain ownership of the land for the affordable housing developments, and partner with third-party developers to design, finance, build, and manage the new units.

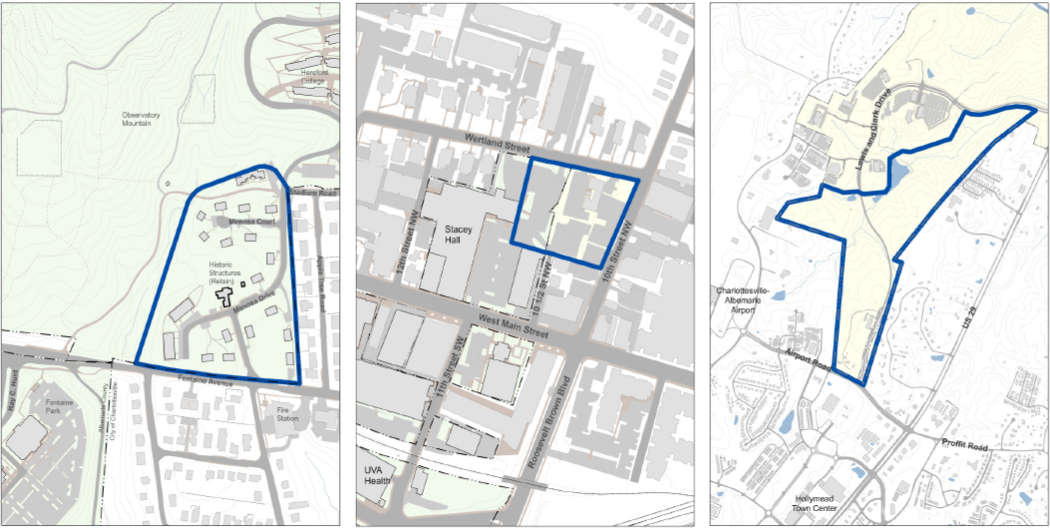

Last month, the university announced three prospective sites—all owned by the university or the UVA Foundation—for new affordable housing units: UVA’s Piedmont community off Fontaine Avenue, portions of the North Fork UVA discovery park on Route 29, and the 1010 Wertland St. building at the corner of Wertland and 10th Street. The existing buildings, excluding a historic structure at the Piedmont site, would be replaced with new ones.

Among the key questions facing the project is just how affordable the units will be. City councilor and longtime affordable housing advocate Michael Payne hopes the dwellings will be available at a variety of rental prices—at all area median income levels. “Our biggest need, and the most difficult affordable housing to build, is having units at zero to 30 percent AMI,” he says.

Moriah Wilkins, Skadden Legal Fellow at the Legal Aid Justice Center, says the units need to be affordable specifically for local residents who make below $50,000 a year. “A lot of the low-income housing tax credit units that we have in the community right now accommodate people who have far more than $50,000, so we need to make sure we’re targeting the right demographic,” she explains.

While the units will be available to the entire community, they should be easily accessible to UVA employees, including dining hall staff, custodians, and other service workers, says Public Housing Association of Residents Executive Director Shelby Edwards.

“People who work at UVA should have the ability to live in the city if they’re going to be expected to work in the city,” says Edwards. “Low-income people, specifically Black people, over the past few years have been moving out of Charlottesville.”

According to a report published by the Charlottesville Low-Income Housing Coalition in 2020, around 25 percent of all city residents currently do not make enough money to afford to live here.

In addition to one- and two-bedroom units, the new developments should have plenty of units for larger households, as well as elderly and disabled residents, stresses Wilkins. It’s also important that the units offer opportunities for homeownership, giving Black residents a chance to build generational wealth.

Payne also encourages the university to explore adopting a community land trust model, in which a nonprofit organization owns land and leases it to homeowners, maintaining permanent affordability. “They’ll be able to reach deeper AMI levels, potentially open up wealth-building opportunities to more people, and ensure that those units aren’t just affordable for 10, 15, or 20 years, which is often the case in some affordable housing developments,” he says.

Two of the potential affordable housing sites, Piedmont and 1010 Wertland St., currently have residents. After receiving some pushback from the residents, this month the university notified those who are eligible to renew their leases that they could do so through spring 2023, and would not have to move out this spring.

“We are beginning discussions about how to assist current residents as we get a better understanding of the needs,” said Assistant Vice President for Economic Development Pace Lochte in an email.

Affordable housing advocates point to Charlottesville’s troubled history of displacing vulnerable residents. In 1964, the city razed Vinegar Hill, a historically Black neighborhood and business hub. Former residents were forced to move to the city’s first public housing development, Westhaven. In 1969, Charlottesville also expanded City Yard into Page Street, another historically Black neighborhood, but refused to assist residents with finding alternative housing.

UVA should start helping residents of Piedmont and 1010 Wertland St. find new housing now, says Wilkins. It should also give them the option to live in the new affordable units once they are built, and offer them the same rental rate they had before—or a lower one, says Edwards.

“It’s really critical to have a survey of everyone who is living in these units who is facing displacement, [and] for UVA to know what their situations are—is it mainly students, community members, how long they’ve been living in that unit, what’s their current rent,” adds Payne. “[They should] use that information to definitely be 100 percent certain that no one is displaced.”

Piedmont residents have echoed these concerns. Since announcing the proposed sites, UVA has been collecting community feedback through an online (or mail-in) survey, as well as a comment wall on the affordable housing initiative’s website.

“If dozens of families lose their homes simultaneously or within a few months, the Charlottesville housing market cannot absorb all of them. Some families might not be able to find a place that is available, affordable, or that will accept their application (because of income, credit score or legal status),” wrote one commenter.

“We just moved in this summer and our new life is just settled down totally. My kids are just get used to their school,” said another resident. “That would be great for kids to stay in same school. Hope we could live at piedmont for full 4 years.”

The 1010 Wertland St. and North Fork sites have received more positive—albeit less—feedback. Commenters would like to see access to public transportation at the affordable housing sites, as well as green infrastructure, sustainable building practices, and community services.

As the project’s team moves forward with the community engagement process, Wilkins urges UVA representatives to visit low-income neighborhoods and public housing communities in person.

“Not everybody—especially low-income folks—has access to the internet and the same resources…so we really need to go into these communities as much as we can and engage in a way that speaks to them,” she says.

Payne hopes UVA will continue to work with local nonprofits, public housing communities, and the Charlottesville Redevelopment and Housing Authority to ensure that the new construction “is meeting the biggest needs in the community” and “won’t have unintended consequences [for] the people around the sites.” He also encourages the school to partner with the city on housing projects that are already in the works, like the redevelopment of South First Street.

UVA is collecting comments from the public until January 31. It plans to issue a Request for Qualifications from developers this spring.

“UVA has been around for so long, and there’s so much undoing of work that needs to happen,” says Edwards. “They started it, and they still have a long way to go.”