Artists Isabelle Abbot and Barbara Campbell Thomas met when Abbot was a student in the MFA program at UNC Greensboro where Thomas was a professor. Thomas became an important mentor to Abbot, helping her achieve a looser, freer painting style and chairing her thesis committee. “Influence + Conversation” at Les Yeux du Monde reunites the two women in an exhibition showcasing their parallel approaches and ongoing artistic dialogue.

The most potent tie linking the two artists is their shared appreciation of the natural world and what this brings to their respective practices. “Barbara has always been very supportive of my time outside in nature,” says Abbot, who became a regular visitor to Thomas’ farm while she was a student. “She talked a lot about note-taking when you’re outside, moving through the world and observing things.”

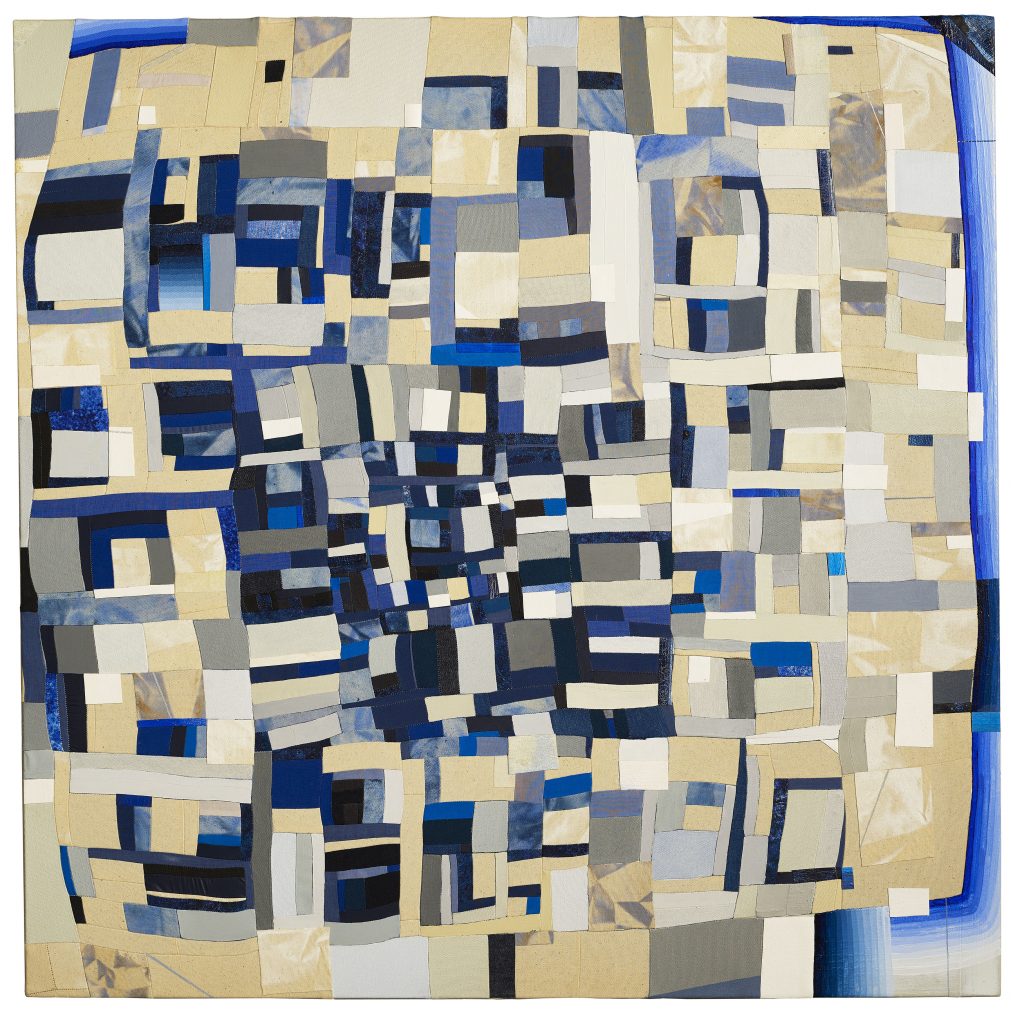

These plein air notes, a central facet of both artists’ practices, help build a visual language they can draw from. Thomas, whose work is abstract, uses what she gleans from her forays outdoors to develop what she refers to as contemplations of an interior landscape. Her paintings combine sewn fabric, collaged elements, and acrylic paint. “I don’t start with a solid piece of material; I basically build it piece by piece, using small sections of fabric, to form a ground that gets stretched. When I’m done with the sewing, I start adding the paint and collage.

“When I learned the technique of piecing fabric together it was like a lightbulb went off. I felt like it was the knowledge I needed. I don’t want to start with a large expanse of unblemished canvas; I want to make that too. It’s not something that’s a given. Instead, I build the ground myself.”

Thomas’ reduced palette of blues and grays is inspired by a rag rug made by her great-grandmother. The rug features a pattern of diamonds, a motif Thomas has incorporated into “Central Medallion.” In this work, the artist plays with space in an abstract way. Surrounding the center diamond, four squares of fabric are attached to each other. Where the seams meet, the strips of material don’t exactly line up, imparting a kind of jangly energy to the piece. Lighter colored painted fabric around the edges frame the dark center, making it pop.

Optically, the thrust of the work appears to be receding down a deep well, while at other times, it feels like it’s extending out toward you. This spatial push/pull animates the work and reveals Thomas’ interest in how movement affects observation. “The visual rhythm and visual cadence of my work is aided by the fact that my body’s in movement,” she says. This attention to rhythm and cadence is also seen in “Night Space,” which features a prominent horizontal direction, and “Dear Star,” which brims with staccato intensity.

Abbot’s connection to the physical landscape is more obvious, although in many works she embraces an abstract direction, using landscape as the jumping-off point. She creates her preliminary sketches outdoors, then takes them back to the studio and tapes them to the wall. “I look at them and see what I would call my go-to marks, my go-to shapes that I put together in different ways.” Moving from one painting to another, you begin to see elements of that vocabulary: descending slopes, triangles, and similar amorphous forms that crop up repeatedly.

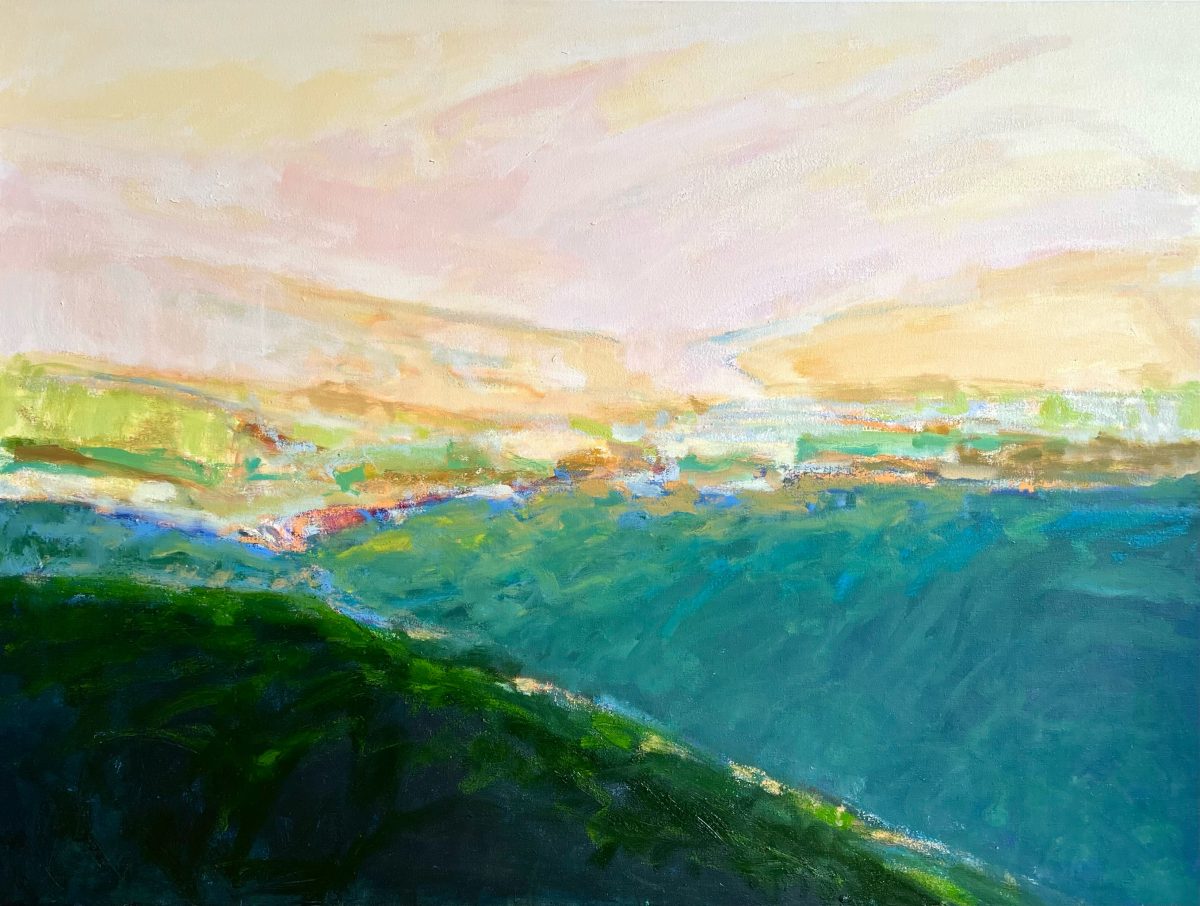

In much of the work on view, Abbot, who excels as a colorist, favors a highly keyed palette of turquoise, yellow, and cerulean. Yet in “Ode to Greenwood,” she uses a more naturalistic color scheme. The painting reads true to nature, but in approaching the picture, you see how the color is created with a gutsy amalgamation of gestural hues that work together to describe reflections on water, the choppy contours of soft, muddy land, and shadows.

In “Morning Glow,” blotches of bright pigment, resembling the fiery flecks that shimmer within an opal, denote pinkish sunlight glinting off structures and objects on distant ridges. The furthermost peaks are washed in pale yellow and pink, and Abbot uses vibrant brushstrokes and vivid aquamarine to convey a mountainside bathed in sun, tempering this bold choice with the dark verdant green of the adjoining hill.

For Abbot, like Thomas, it’s not just being in nature, but moving through nature. “For a long time, I painted the landscape like I was looking out a window at it. I framed it and composed it and then painted it.” But now she tries a more immersive approach, capturing the landscape in a holistic way. “It’s something that’s not way over there … you’re in it.” You see how this is implemented to great effect in “Field’s Edge,” a pastoral scene that is not just a stunning image, but is infused with the sensual qualities of its subject—buffeting breeze and warm sun—elements experienced by the artist firsthand and interpreted so effectively for us using her personal artistic language.