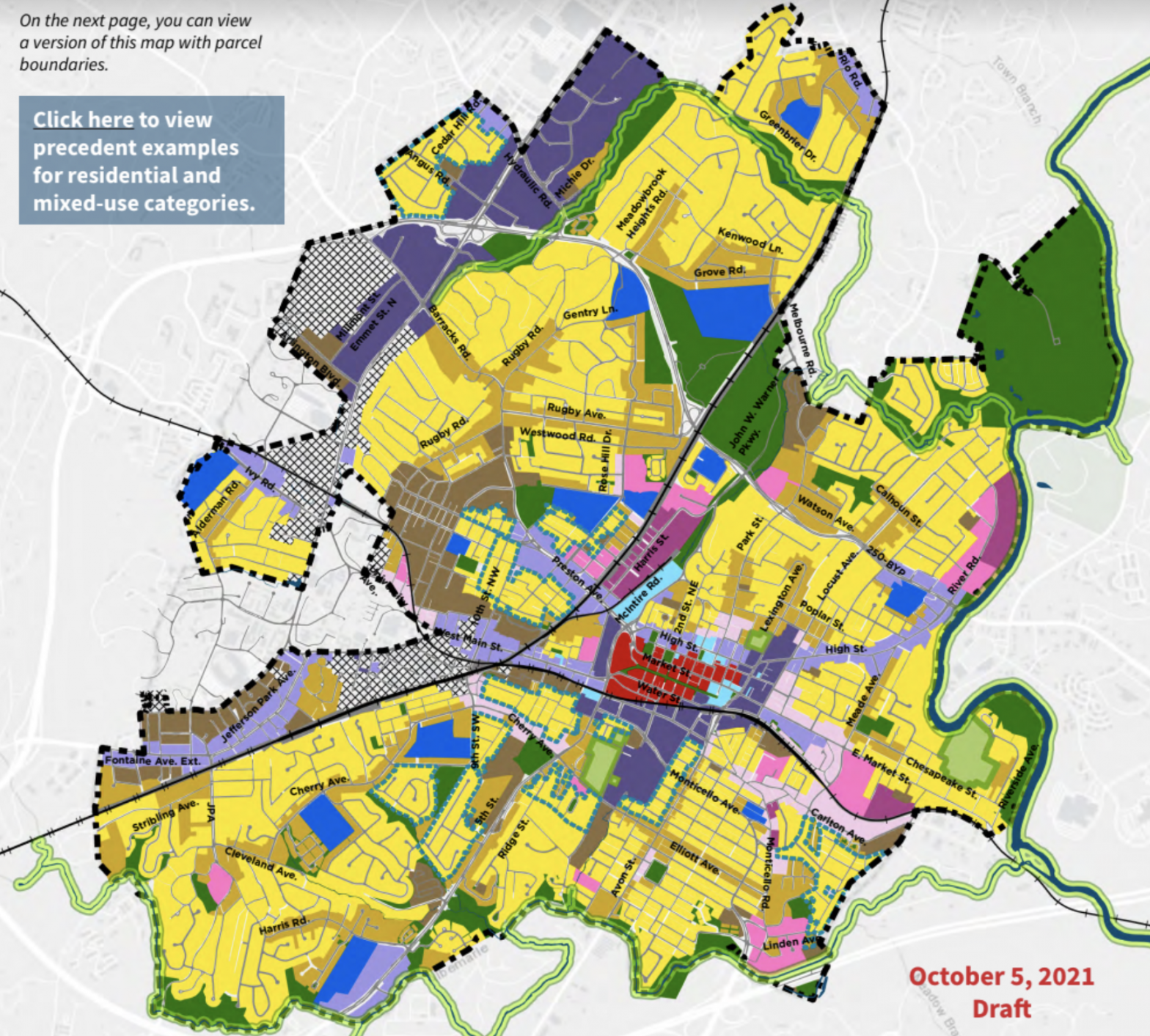

Ask anyone about Charlottesville’s most pressing problems, and chances are affordable housing will top their list. The city’s new Future Land Use Map, adopted last November as part of the comprehensive plan, has been touted as a solution. It aims to increase housing supply by allowing greater density in every city neighborhood from three units per parcel in general residential areas to more than 13 units per parcel in areas designated high density. While the details of the zoning are still being worked out, the plan has been met with fierce opposition.

First came a lawsuit from anonymous plaintiffs alleging the city violated state law when it adopted the FLUM. After three of the four complaints in that suit were dismissed by a Charlottesville judge in August, dozens of city residents have now signed an open letter that claims the process to create the Future Land Use Map has been “flawed from the beginning” and that it is not the best way to accomplish the city’s affordable housing goals.

“Insufficient data was collected, insufficient analysis was done on data, insufficient citizen participation was solicited, which led to a faulty diagnosis of the problem in Charlottesville with housing affordability, which is leading now to a proposed treatment which is not indicated,” says Ben Heller, one of the city residents who signed the letter.

“The idea of upzoning is [that] pure density solves the problem, and it’s not been demonstrated in any city that’s tried it,” says Martha Smythe, another letter signer.

The letter’s other stated concerns include that the city’s consultants never provided the number of needed units at various levels of affordability, that the Plan did not address the infrastructure needs of the city today or those required to accommodate implied future growth, and that the character of existing neighborhoods is threatened.

“The idea of going and upzoning the whole city, if you stop and think about it, feels very much like trying to make amends for past faults and past issues,” says another letter signatory, Philip Harway. The FLUM “feels like our elected and appointed representatives are throwing a Hail Mary pass.”

Vice-Mayor Juandiego Wade, who had just been elected to council last November when the previous council voted to adopt the FLUM, disputes that characterization. He says the actual zoning ordinance will take about a year to be finalized. Even then, council can make adjustments.

“If we approve something and two months or two weeks later, we see something needs to be changed, then we can change it,” he says. “I see it as a dynamic process.”

The other councilors were either unavailable or did not respond to a request for comment.

Real estate analyst Quinton Beckham, principal broker for K.W. Alliance, agrees with the letter’s claim that higher density alone will not solve the affordable housing crisis.

“How this affects affordable housing in our city is one cog in a very, very large machine,” says Beckham, noting that the lack of housing inventory does contribute to the high cost of homes and increasing the number of units will relieve some of the market pressure.

“Every person that we get placed is one less person that strains the system,” he says. Beckham disputes the letter’s claims that higher density creates more traffic—“it’s sprawl that increases traffic”—and says greater density reduces other costs associated with growth.

Developer Kyle Redinger also disputes some of the letter’s assertions and says Charlottesville hasn’t kept up with the pace of housing demand. He says greater density is overdue.

“When people see the zoning opportunity, they get nervous because they think they’re going to have a lot more density in their part of the city. And the reality is, that should have happened 20 years ago,” he says. In his opinion, the FLUM doesn’t go far enough.

“If your goal is to solve housing affordability, any restrictions or barriers to land use has to be done away with,” he says.

The controversy is likely to continue as the city completes the zoning process. Heller says more specifically targeted density should be a part of the affordable housing picture, but he says there are better solutions than zoning.

“We could look at making it easier to convert commercial centers to residential housing. We could look at land trusts where the city contributes its own land to developers in exchange for affordable housing,” he says.

While Habitat for Humanity and Piedmont Housing Alliance are the major players in constructing Charlottesville-area affordable housing, Heller believes there are other organizations in the country that could do the same work for lower per-unit price.

Wade says council is “listening to what people have to say,” but Harway claims better communication and more public input during the process would have reduced some of the current opposition.

“I think there’s really an issue of trust with the city that a lot of residents have expressed to us that they do not trust what the city’s doing as being in their best interests,” says Harway. “And, yes, these are mostly middle class folks. But they’ve been paying the taxes for, you know, as long as they have owned homes here. And to ignore them and put them at risk is certainly not a smart move.”

Courteney Stuart is the host of “Charlottesville Right Now” on WINA. You can hear interviews with Martha Smythe, Ben Heller, Philip Harway, Quinton Beckham, and Kyle Redinger at wina.com.